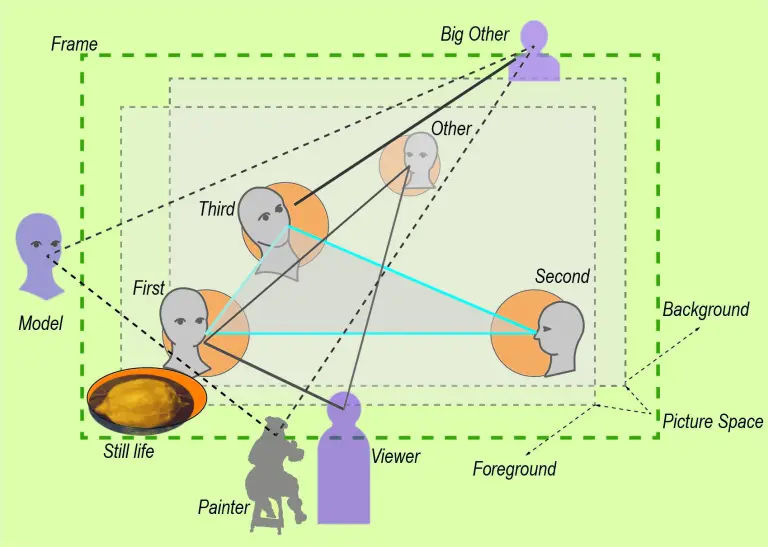

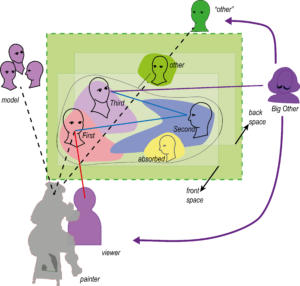

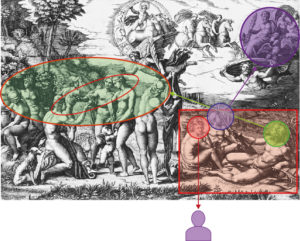

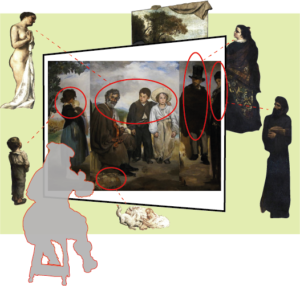

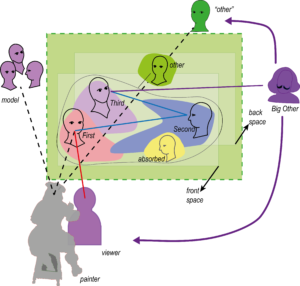

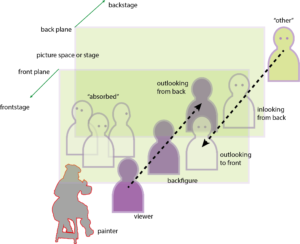

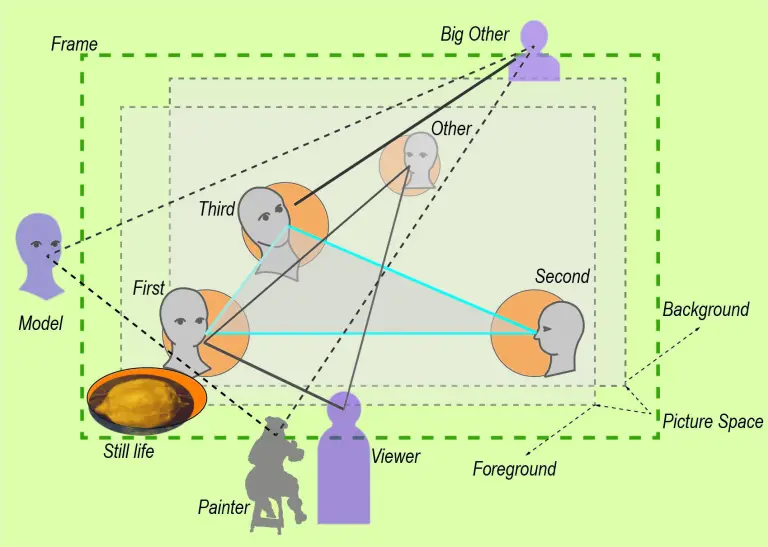

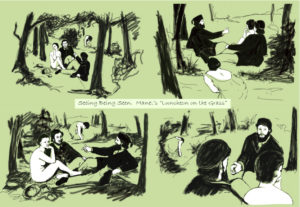

In my diagrammatic artwork “Seeing Being Seen” I tried to capture the changing perspectives on the scene of Luncheon on the Grass which a viewer walking around Manet’s “installation” would experience.

Confronted with the painting itself, a viewer will first be engaged by the gaze of the nude woman looking directly at the viewer – see the sketch in the lower left of Figure 1.

Her gaze includes the viewer as an onlooker, if not intruder, to the scene – we are drawn into the painting.

Figure 1: Seeing Being Seen. Manet’s “Luncheon on the Grass” (Pieper 2020)

Being part of the scene, the viewer might follow the gazes of the other participants. We all have the natural disposition to do that.

Besides the woman’s perspective on the viewer (lower left in Figure 1), there are three perspectives, one for each participant:

Looking at the man to the right (the Second in Manet’s scheme), it is somewhat unclear who he is looking at, since the other two are clearly not responding to his gaze.

Following his gaze, we would stare into the trees to the left. Imagining walking around to the left and stepping into the line of his gaze, we might get a view like in the lower right of Figure 1.

Turning our attention to the other man (the Third in Manet’s scheme), his gaze is somehow trailing off beyond our right shoulder directed toward something or somebody beyond the more immediate scene. Following his gaze, we expect seeing the empty sky (or Nadar’s balloon, as suggested previously).

Stepping into his gaze appears to be impossible; we would have to imagine floating somewhere in mid-air looking down at him.

This is the perspective of the upper left in Figure 1.

Then, the viewer will become aware of the woman in the background. Her involvement with the group is obvious (she is even somewhat imposing herself on the group by being too large for her distance from the group), but she is looking at the group only from the “outside” in her peripheral vision.

Following her gaze will not reveal much, but imagining looking over her shoulder, as in the upper right of Figure 1, we become aware of the group as seen through her eyes “from the back” of the painting.

At this point, we “see” that we – the viewer – are not “really” included in the painting but in front of it:

We were sent on a walk around within the painting.

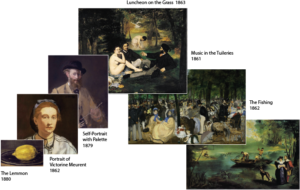

In MyManet, we assume that Manet was more or less intentionally trying to engage the viewer in this kind of walk. He wanted to make the viewer aware of the perspectives of the agents involved rather than arresting his or her imagination in the single viewpoint of the physical perspective looking through the “window” of the frame.

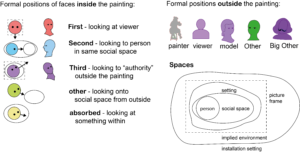

So far, discussing Manet’s scheme, I have paid attention only to the figures within the painting and the targets of their gazes identifying unrepresented agents outside the painting like the viewer or unrepresented “others”.

In view of MyManet, one way to enter the scene is to keep our position and to follow the gazes, but that seems only to point to unrepresented agents outside the painting. The development of Manet’s scheme was guided by this approach.

Another way is to “face” the figures as imagined in the walk described above.

In the imaginary walk, we also look back at the figures in the painting from positions outside the picture space. On this walk, the figures would “experience” being seen by us, and we “experience” seeing them while being seen by them.

Let us take a closer look at this “seeing being seen”.

- Seeing being seen (Figure 1 lower left)

In the case of the nude looking at us, the viewer, she is seeing us and she is aware of being seen by us.

The view is reciprocal – both are aware of seeing and being seen – and her little smile seems to be somewhat inviting, although not really committing. Since the other figures are – for the moment – not looking at us, her gaze and her smile is quite personal.

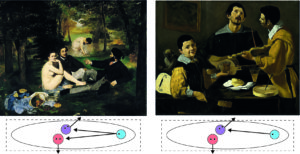

This intimate reciprocity is a special feature of Manet’s Luncheon and, in my view, accounts for much of its enduring attraction for viewers. We find the engaging gaze of a central figure in many paintings before and after Manet. Rembrandt and Velazquez in the previous posts provided great examples. But in Luncheon Manet succeeds to engage us in a way which I have not (yet) found in another painter.

In most cases, “seeing being seen” on part of the figure in the painting is only an imputation by the viewer. Following the laws of perspective, the figure looking out must see the viewer looking in. A common space for seeing each other is produced.

But the viewer does not feel addressed personally, even when affected emotionally; there could be any other viewer in front of the painting. The viewer does experience “being seen” but does not feel “engaged personally while looking in”. Portraits typically create this experience.

In other cases, there is an explicit attempt to communicate with the viewer to arouse certain feelings, for instance, of sympathy for the depicted poor child or of being threatened by an aggressor. An obvious case are erotic paintings where the depicted figure tries to allure the viewer. But this kind of “story” is not supported by Manet’s scenes.

In my view, the difference is that the viewer does not recognize and accept the woman “as a person” but only “as a painting of a person”. For the personal experience, it seems necessary that the depicted person somehow claims the “recognition as a person” successfully. How Manet achieves this – in different ways in his figurative paintings – is the secret of his painting and is, I think, at the heart of his realism. His figures – at least the focal figure – are realistic because they are recognized as subjects and not just (visual) objects. The question is not just “What pictures want?” (Mitchell) or the “facingness” (Fried) of the painting, but that there occurs a “picture act” (Bredekamp) on part of the specific person depicted.

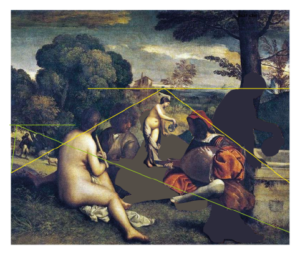

What seems to be essential in the case of Luncheon, is the element of a specific collusion with the viewer, an invitation to move around in the space defined by the gazes in the painting – not defined by the law of perspective (violated by Manet) and without committing to a “story” (avoided by Manet).

Besides the sympathetic gaze of the nude, this invitation is created by a puzzle:

– on the one hand, the lack of coordination of the gazes calling for an explanation

– on the other hand, the impression of a “staged” or constructed scene suggesting the existence of a hidden meaning.

This impression is enhanced by the fact that there is a minimal set of actors and that any obvious interpretation or narrative – like two ladies and two gentlemen having some fun – is not readily supported.

Thus, we are led to engage and to solve the puzzle – and solutions or interpretation have been suggested for over 150 years now. (My Seeing Being Seen is just another humble example among countless others exploring the puzzle with a diagrammatic approach.)

In the Luncheon, facing the nude, the collusion is enhanced by a layer of ironic distancing, because it seems to be Victorine, the model, who is giving the little smile rather than the sympathetic but anonymous nude sitting there on the grass. The smile of the nude would make the viewer feel “caught looking”, which we find in many erotic paintings and pictures, also in the exhibition of the Salon at Manet’s time. The smile of Victorine adds a specific subjectivity of “seeing being seen”.

This double-layered collusion between figure/model and viewer is needed in Manet’s scheme only when the First looking at the viewer is the focal figure and when her smile may be misinterpreted as “telling the wrong story”. Manet wants to invite us into a social space but not into an erotic scene.

For instance, in The Balcony (1868) with Berthe Morisot looking to the left out of the painting, Fanny Claus is in the role of the First engaging the viewer but needs no ironic distancing. Her “seeing being seen” supports the public situation on the balcony. (The fact that the insider may know the true identities of the models is not an essential element of the painting, it “works” without that knowledge.)

In another case, Nana (1877), the girl is looking somewhat flirtingly at the viewer, “seeing being seen” (Figure 2). The smile fits the “story” of a high-class prostitute finishing her make-up with her client waiting on the sofa.

Figure 2:

There is a lot of irony in the painting, but no distancing between the model (an actress) and her role in the painting. (The “story” is one reason why Nana is not a “clear case” of Manet’s scheme, as I will try to show in a later post.)

This experience of “seeing being seen” by both the viewer and a figure in the painting is an important element in Manet’s scheme. However, variations of the scheme may place this mutual experience between viewer and depicted figure into a side role, as in The Balcony.

- Seeing others [while unaware of seeing being seen]

(Figure 1 lower right)

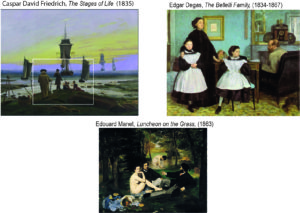

Seeing others (usually, but not always) within the picture space is the role of the Second in Manet’s scheme establishing the social space from within. This gaze invites the viewer to follow its line of sight in the picture, a natural reaction of the viewer, and to look at the other participants and/or to imagine what this person is seeing of the scene what we might not be able to see. This gaze places the person into a position in the painting where we cannot see his face directly creating a need for us to change position (or to hope that person to change), since we also want to see who is looking and complete our view of the scene by the view of the other.

Imagining, as viewer, moving to the left among the trees and stepping into the line of sight of the man to the right, we would see his face looking in our direction. But his seeing us will be non-engaging, perhaps not even noticing the viewer between the trees looking in his direction. He is looking at the other two figures trying to get their attention. Maybe in the next moment, he will be following the gaze of the nude and see the viewer in front of the scene who is imagining seeing him from among the trees…But in this moment, the viewer is “seeing” someone who is not aware of “being seen”.

We experience this often in busy streets when other people appear to be looking at us, but not really “seeing” us, and unaware “being seen” by us.

Actually, I found it quite difficult to depict this “accidental” gaze in my painting (Figure 1 lower right), because somehow, as the painter (or the photographer), one has to prevent the viewer from engaging with the gaze directed toward him or her. In a real-life situation, we simply “know” that a gaze is not “meaning us”, and we avoid catching the attention by looking only peripherally at the person.

In paintings, we often find this accidental gaze at the viewer, but then, we are – as viewers – treated as accidental onlookers (through the “window” of the frame) and/or we are obviously excluded from the “story” being told.

Walking around Manet’s painting, as imagined here, we tend to transfer the immediate engagement experienced with the first person into the imagined entering of the line of sight of the second person. Showing the gaze of the Second as a gaze not “seeing being seen” is not really achieved in Figure 1. Manet, however, is frequently depicting persons as not really – that is, fully aware – seeing the viewer or other persons in the painting.

For instance, puzzling in looking back at the man in Figure 1 (lower right) is the fact that he is not really focusing on any of the two others. We sense this already when looking from the front. There it adds to the lack of readability of the situation. While we have assigned to the Second in Manet’s scheme the role to establish the picture space within the painting by looking at the other figures, we now see more clearly that this does not imply a clear focus on those others. In The Breakfast (1868), we have seen that the man sitting at the breakfast to the right (the Second) is looking across the picture space without regarding the boy in front or the maid in the background.

In his later paintings, varying the scheme, Manet will often apply this “accidental” gaze, not clearly focusing the viewer or something in the picture space, to create a distancing effect while at the same time zooming in closer toward the subject.

The most famous example is, of course, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), his last great masterpiece.

However, in view of MyManet, the gaze of the barmaid may be seen in different ways.

We will return to it in a following post.

Here, we keep in mind for Manet’s scheme that “seeing being seen” might be a rather peripheral vision for those figures who are establishing the social space by seeing others. Moreover, seeing others will often – and for Manet typically – not imply focusing clearly on those others.

- Seeing [without seeing something in the visual space or being aware of] being seen (Figure 1 upper left)

This case is characteristic of the man sitting next to the nude, the Third in Manet’s scheme. In the upper left of Figure 1, the viewer tried to intercept the gaze of the other man somewhere in mid-air looking down at him.

But the viewer will not imagine that the man will be “seeing being seen” by somebody up there.

For the viewer, the case recognizes that we are aware – when looking at somebody – whether his or her gaze is “looking at” somebody (or something) in the common visual space, or not.

The gaze may be directed “inside” trying to think or (day-)dream of something not present, or directed “outside” imagining something not present in the visual field. Such a gaze can overlook an onlooking person within the painting or overlook the outside viewer even when being directly in the line of sight of the person.

Walking “around” the painting, this case is easily confounded with the unfocused gaze of the Second above.

Imagining looking into the face of a person not clearly focusing, and

imagining looking into the face of a person not looking at something in visual space becomes easily a matter of interpretation.

But in principle the distinction is clear: there is a difference between the unfocused gaze often required in a more complex situation involving e.g. multiple participants, and the unfocused gaze not looking at anything in the common visual field.

- Seeing [what is] being seen [by others within or outside the picture space]

(Figure 1 upper right)

We communicate about the persons and objects in our common visual space effectively without thinking much about the fact that the visual field is different for each one of us. We see the objects from different angels and face some people while others are looking away from us.

Routinely, we complete the partial view we have to a 3-dimensional visual space with 3-dimensional objects. We assume that we can “see” what other persons see, since moving around we continuously complete and update our view of objects and experience that the other persons do the same.

Thus, “seeing what is seen by others” poses no problem, unless seeing what we from our perspective cannot see at the moment becomes relevant in the interaction. This applies typically to things in our back, to the other side of things in our view, and things beyond our visual field.

It applies also to our own face. This is why the faces of others are so important. Their faces and reactions show us who we are.

An interesting case, often explored in paintings, is the view into the mirror which shows what the viewer or the person in the painting might otherwise not see. The problem with mirrors is that they show the things reversed. Placing a mirror behind the group in Luncheon, the viewer would see a reversed image – not what the person in the background would see!

Manet’s most famous painting featuring a mirror is, of course, A Bar at the Folies-Bergére (1882). We return to the case of mirrors when we look at this masterpiece.

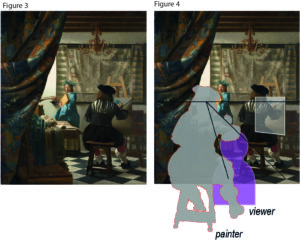

Paintings are 2-dimensional, unlike sculptures and installations, and, therefore, we cannot walk around and get the 3-dimensional picture. Paintings showing a naturalistic perspective only succeed in pinning the viewer down to one position. Paintings showing persons aggravate the problem, because in reality they, in particular, are moving and changing their perspective on things. Casting them into a system of physical perspective only makes matters worse.

MyManet suggests that Manet – among other painterly means – tried to find a solution by detaching the figures from a fixed frame or background creating a kind of mobile with puppets hanging “on stage” in a picture space. This, we have shown already in previous posts. He was fascinated especially by Velazquez’ way of placing a figure into a diffuse background, a strategy, which Manet applied, for instance, in The Fifer (1866).

Another strategy by Manet is, in view of MyManet, the creation of a social space reaching beyond the picture space and stabilizing, as it were, the mobile by the system of gazes and gestures. By not using the perspective system and physical space, he allows for the imagination of the viewer to move more freely within and around the painting.

In this strategy, the perspective from the back becomes an important element.

(Alternatively, as we have seen in previous examples, Manet closes the background and moves the picture space towards the viewer. That way, like in a small theatre, the viewer is already “in the middle of it” and needs no “view from the back”.)

Handling the view from the back is, however, a delicate challenge.

In Luncheon, we find the other woman not looking straight at the group, although she is clearly oriented toward the group.

If we imagine the woman in the background looking up and straight at the group, the viewer – or an unrepresented person next to the viewer – would be in her line of sight. The viewer might feel an urge to follow the gaze and look away from the painting to the left or right in the viewer’s space. Rembrandt played with this effect, as we have seen in the last post. Manet avoids this effect, presumably because he wants no distraction from the engaging gaze of the first woman.

The “Other” in his scheme is never competing for the attention of the viewer but suggesting another position and perspective to be taken by the viewer completing his or her view by imagining “seeing what is being seen by others”.

In MyManet, we assume that Manet is exploring these complex views with his scheme. The Luncheon on the Grass is his model case. Moving his actors around in the picture space, their gazes create different compositional challenges in those paintings, as we have seen.

The greatest challenge Manet addressed when he reduced the figures to one person and substituted the other participants in his scheme by mirror images: A Bar at the Folies-Bergére.

Let us take a look at this masterpiece!

A personal note: Unfortunately, I got hit by Covid and I am still recovering.

This post is about a week late and turned out to be quite a demanding effort.

Hope to see you well in two weeks!