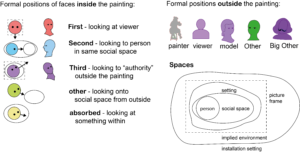

In the previous post, we distinguished 5 positions inside the painting.

(see Figure 1 in Post 5)

Now, we consider the positions outside the painting:

Who is looking?

Or as the question in Installation My Manet has it:

Question 4: What kind of social roles are involved outside the painting?

For the answer, we turn to Gustave Courbet (1819 – 1877) :

Figure 1: Gustave Courbet The Painter’s Studio – A Real Allegory (1855)

(with red ellipses added)

Unlike Vermeer, who depicted only himself and the model (see Post 1), Courbet shows himself in a crowded studio with all the members of society relevant for his realistic painting – with himself in the centre!

In the centre, the nude model looks over his shoulder – although he is painting not her, but a scene from his home province. Well, a nude is always helpful to get (male) attention, and the nude signals serious painting.

The little boy with the cat is allowed to take a closer look, and seems to admire the artist more than the painting.

To the left, we see members of society – both poor and rich (the sitting man with the dogs may be Napoleon III).

To the right, members of the art community are gathered: friends, writers, artists, art lovers, critics, and financiers (at the right edge, reading a book and not interested: Baudelaire, the realist writer and Manet’s friend).

Notably, only two people – besides the inner (red) circle around Courbet – are really interested in the painting (marked with red ellipses).

To the right, there is a woman looking over her shoulder from behind;

to the left, and at the very edge, we find an old Rabbi or philosopher observing the scene.

The others, presumably, play a role in the allegory of Courbet’s life, but they seem to be present just to support the Grand Ego of the painter.

Thus, if we count only the interested persons, we find 5 positions and social roles outside the painting:

The painter

The painter is clearly shown as independent, creative and skilled to transform ideas with paint into a visual object. There is a personal life depicted leading Courbet from his rural provincial region to the centre of French culture and society.

Painting is shown in a social context, but the context is not really involved in the process. The painter is the centre of the activity.

With Manet, the painter is present and active, but not represented.

The model

In Courbet’s painting, the model has a curiously passive role standing behind the painter, while he is painting his own provincial background.

As we will find, the model has a crucial and active role for Manet. In Luncheon on the Grass, the model has direct eye contact not only with the viewer, but also with Manet, the painter.

Manet preferred models interested in his art (family members, friends, supporters) and artists like his favourite model Victorine Meurent (who not only modelled but painted herself) or his friend and painter Berthe Morisot.

We will return to the relationship of Manet and his models.

The viewer

Courbet clearly takes pride in collecting a large group of viewers around him – he was a great painter, but also a great marketer of his art and engaged in public life. Paintings are created to be seen! And for Courbet, the painting can and should talk to the viewer, even presenting an allegory of a painter’s life.

For Manet, the communication of ideas through painting is a much more subtle thing. The viewer has a role in understanding and interpreting the ideas of a painting, but Manet is not telling the viewer a “story”.

In the reflection on the “painting of painting”, the painter is his own first viewer. Other viewers may be present on a visit to the studio or are an anticipated audience (if only in the museum), but they do not enter the painting.

Still, their viewpoint in front of the painting plays an important role in the composition, and their view, their anticipated reaction, and their role as customers influence the painting process.

The critic or the “other”

Members of the art community, critical evaluators including the artist’s friends, are vital because they provide the examples, role models, and feedback for the painter.

Courbet sought independence in his Realism from traditional Romantic schools early in his career – perhaps, this is why the group of artists and critics in the painting is somewhat distanced to the side. Still, he was well aware of the importance of the art community for his work.

Manet – besides attending for six years the art school of Thomas Couture – also was an integrated member of the art community, although in his own circle. Artists and critics were frequently visiting in his studio and he visited them in return.

While a painter is foremost his own critic, “others” taking a different perspective “from the back” were not only a virtual, but an actual presence in his painting practice. Charles Baudelaire, for instance, is said to have visited Manet almost daily. In later years, Stephane Mallarmé was another friend, art critic, and regular visitor.

The “Authority” or Big Other

Courbet does not include a reference to art traditions or a gaze outside the painting to any authority, he paints himself as the authority.

Manet valued highly the tradition and institution of art, and sought the recognition by the Academy of Fine Arts – eventually to present his art in the Louvre Museum. He initiated a “revolution” in art, but only because he sincerely pursued his own way of painting, not respecting established norms just because they were established. Unlike his Impressionist friends, he always tried to mediate between tradition and innovation.

He never founded an own school but experimented with different styles and built bridges between schools, past and present. The Great Masters – like Diego Velazquez, Antoine Watteau, Titian, and Frans Hals – gave him guidance. But he did not follow them.

Perhaps most telling of his independent orientation toward a more abstract ideal or “authority” of painting is the fact that he never really joined the impressionists, although he kept close contact with their community.

And he never styled himself as a genius transgressing the achievements of his predecessors (like Courbet). But he created his personal style, and art historians to this day have problems with assigning him to any particular “-ism”.

Velasquez was his idol all through his career – that is why I chose to take the Master’s silhouette as an icon for the “authority” in the diagrams.

I also like the term “Big Other” for this external referent, because it eases the connections between the “other” – as a different perspective by others in the social context – and the “Big Other” – as an authoritative value reference in art.

Different Interpreters of Manet’s art invoke different “authorities” (e.g. philosophical, historical, psychoanalytical, political, or even ethical frames of reference) and propose their relevance for understanding his art.

At this point, we just introduce this distinction, and will discuss different interpretations when they become relevant for understanding Manet’s paintings.

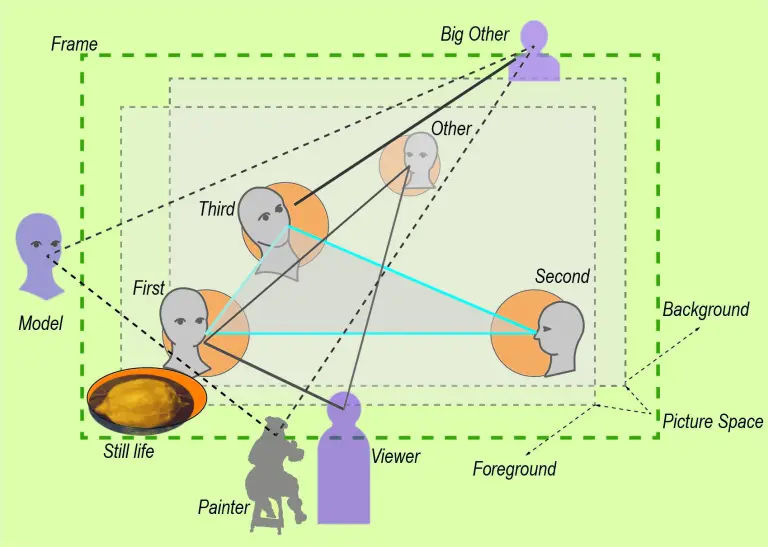

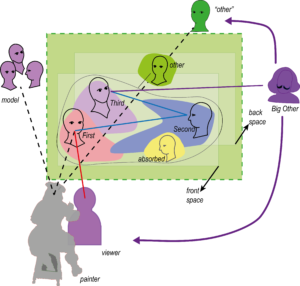

Now we can combine the positions or roles in our scheme: (updating the version of Figure 4 in Post 2)

Figure 2: Positions and social roles inside and outside the “painting of painting”

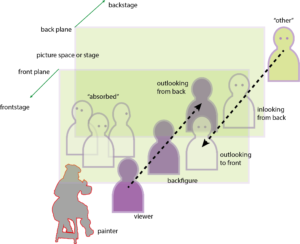

The diagram shows again the painting with its “stage” between front space and back space. The triad takes a prominent role within the painting with the onlooking other (green) and the absorbed other (yellow) playing supportive roles. The gazes of the figures create a social space within and are reaching out to the agents outside the painting. They relate the represented social reality within the painting to an unrepresented social reality outside.

The diagram differs clearly from the scheme for Vermeer, because it distinguishes a plurality of positions beyond the painter, the model, and the unrepresented viewer.

It is also different from Courbet and Velazquez and their depiction of the “painting of painting”, since they represent the painter within the picture.

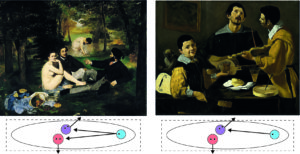

Courbet, moreover, does not include the First – the direct contact with the viewer – or the Third – the gaze to an authority, unlike Velazquez.

As we have seen in Music in the Tuileries and The Fishing (Post 3) , Manet does include in some cases himself in a painting, but not in a prominent role. He appears as part of the depicted theme: as member of the art community enjoying their time in the park, or: as member of the future family (since The Fishing has been interpreted as a promise and announcement of his marriage with Suzanne, the mother of his son Leon depicted on the other side of the river).

The diagram, obviously, anticipates the composition of Luncheon on the Grass. We just have to drop the absorbed figure from the scheme. This raises the question, whether the scheme is only an abstract model of this specific painting. The thesis of MyManet proposes more, namely,

that the diagram is a generic scheme for other paintings, too, and that

the Luncheon on the Grass should be read as a programmatic statement about the “painting of painting”.

To support this thesis, we will look at a painting that precedes the Luncheon, and which MyManet understands as a first attempt by Manet to combine insights from his study of Velazquez and Courbet (and other paintings) in a programmatic way.

The painting is The Old Musician (1862), created just a year before the Luncheon and considered by many art historians as basic for Manet’s art in the early 1860ies.

See you next week!