Enter Berthe Morisot!

In The Balcony, she is painted by Manet for the first time and certainly “frontstage”.

And I was able to see her last week visiting the Museum D’Orsay in Paris!

As expected, the original was much more impressive than any of the reproductions.

Manet took his inspiration from a painting by Goya (or from engravings made from the painting).

But again, there are interesting deviations making the painting a variation of Manet’s scheme!

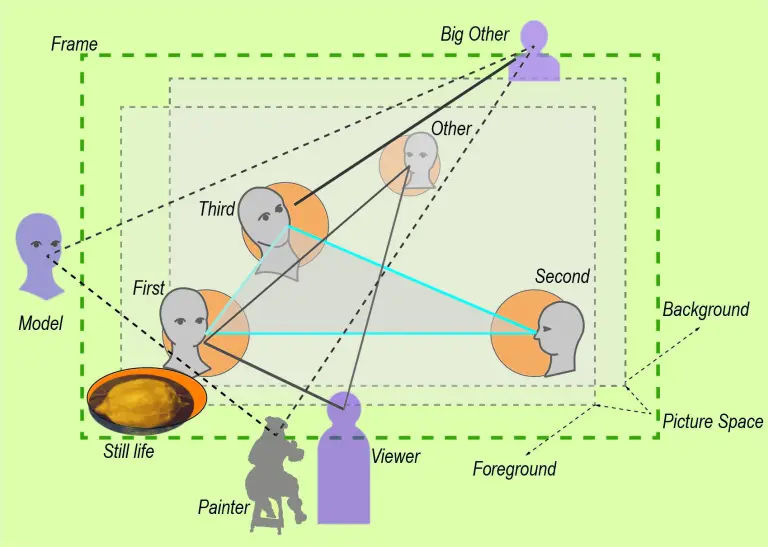

Figure 1: Manet The Balcony (1868) and Goya Majas on a Balcony (1800)

Discussions of the painting typically focus on two aspects imposing themselves on the viewer on first glance, as I can confirm:

the strong composition with contrasts of colours and the presence of Berthe Morisot.

The composition balances different forces:

Like Breakfast in the Atelier (see Post 18 and 19), the viewer is somewhat disoriented by the divergent gazes of the figures directed out of the painting and almost tearing the picture apart.

This is what Lüthy (2003) called the “situative incoherence”; the figures seem to be in no transparent relationship to each other and not involved in some common activity.

But the painting displays a clear geometrical order with a triangle of three figures framed by the intrusive green colour of the railing and the shades on either side cutting out an almost square “picture in the picture” in the upper half.

This strict order might have motivated Magritte to place four coffins on the balcony:

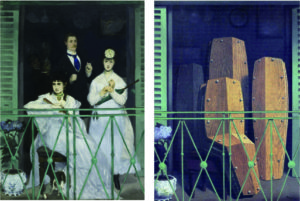

Figure 2: Manet The Balcony (1868) and René Magritte The Balcony (1950)

Although, the “gazes” and “bodies” of Magritte’s coffins seem to form a rather social group turning toward each other. Magritte apparently suggests that Manet’s figures are even more isolated than coffins.

Actually, the coffins remind me of the group in Luncheon on the Grass – perhaps another hint by Magritte?

Concerning the composition, Sandblad (1954) proposes a strong influence of Japanese woodcuts creating a “decorative unity” of the elements. In the previous year 1867, Japanese art was presented to the French public in the World Exhibition, and Manet was surely motivated to compete with this style which he admired, and which was consonant with his own ambitions.

But, obviously, Goya and the Spanish tradition also inspired the painting.

And, typical for Manet, we find allusions to own paintings, especially, with the boy in the dark background reminding of previous appearances of his son Leon (interestingly, at a much younger age in the painting than in Breakfast of the same year).

Most striking is the way Manet has placed the figures in the foreground, almost before the picture space. The figures literally sit or stand “out on the balcony”. We don’t see the anchoring of the railing in the floor, the figures float in space, and the black background further pushes the figures toward the viewer.

In Goya’s painting this effect is not so pronounced, because the railing is moored to the floor and the woman’s foot is resting on a beam fixing the railing.

Additionally, the three figures are highlighted by colourful accessories: a red fan, a green umbrella and a blue tie which stand out much more in the original than in any reproduction I have seen.

In this confrontation of the viewer, the painting reminds of modern advertisement strategies. Viewers at the time were not so used to this “pushing” design. As Dombrowski (2010) suggests, Manet might quite deliberately have chosen this composition to make the painting stand out, in case it would end up in an unfavourable place high up on the exhibition wall.

The presence of Berthe Morisot is the other striking feature.

Her gaze is responsible for “the deep secret behind this picture – the beauty and intensity of life itself” (Georges Bataille 1955, p.85).

The Balcony was the first of a series of paintings and sketches Manet made of Berthe Morisot over the next six years until she married his brother Eugène in 1974.

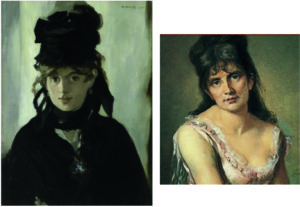

In Figure 3, we see her famous portrait by Manet (1872) and the detail of a portrait by Marcello (1975). (Marcello was actually the pseudonym of Adèle d’Affry, an acclaimed female sculptor and painter and friend of Morisot, who chose a male artist name to be accepted in the male art community. Today, you can admire her sculptures in the Museum D’Orsay next to works by Manet and Morisot. Pino Balsone made me aware of this portrait – thank you!)

Figure 3:

Manet Berthe Morisot (1872) and Adèle d´’Affry (1875) Portrait of Berthe Morisot (detail)

Morisot was a founding member of the impressionist movement and an artist in her own right, but in books about Manet she features especially as his muse, model, and – possibly – lover.

Art historians are still not sure whether the two had an affair or not, but I agree with Beth Archer Brombert (1991) that this is really irrelevant.

What we know is that the two were loving friends and – looking at the two portraits – we understand why Manet would love her and feel that she looks lovingly back.

In view of MyManet, two things are more important:

that Morisot influenced Manet (more than he influenced her) to try a more impressionistic style of painting, and that this apparently had an impact on his pursuing Manet’s scheme.

Until December 1874 – her marriage with his brother – she was Manet’s favourite model; in 1875 he made his last impressionistic painting (The Laundry). During this period, Manet produced a great variety of paintings including non-impressionistic works, but nothing clearly following MyManet.

Why?

Afterwards he painted Parisian life (trying to suppress his feelings for Berthe Morisot?). The painting of a demi-monde woman – Nana (1977) modelled by an actress – was the next painting following more readily Manet’s scheme.

(There are two other famous paintings – The Railway (1873) and Argentuille (1874) – one featuring as model Victorine Meurent (!) and the other an unknown “loose” woman – which show elements of the scheme; we look at them later.)

To understand what happened in view of MyManet, let us take a closer look at The Balcony.

In a first step, we recognize Manet’s strategy to choose an example from the art tradition, in this case, Goya Majas on a Balcony (Figure 1).

Comparing these figures with his group in The Balcony, we see that Manet again rearranges the gazes and positions. In Goya, the women lean toward each other forming a couple with one woman looking down into the street, the other gazing upward and somewhere out of the picture. Behind them we identify two men “looking from the back”.

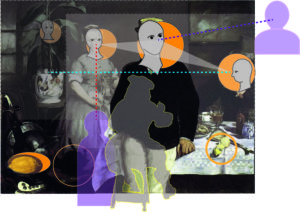

Figure 4: Manet’s Scheme applied to The Balcony

comparing with Breakfast in the Atelier

In The Balcony (Figure 4), we find a triad – like in Luncheon – only that now the woman to the right is looking at the viewer (First), the man is looking upward and out of the picture (Third), and the woman to the left, Berthe Morisot, directs her gaze to the left out of the picture into the street.

In view of Manet’s scheme, we would expect her to take the position of the integrating person (Second) looking at the others. However, Manet has placed her on frontstage (and to the left) where she cannot make eye contact with the other two.

Comparing the Breakfast in the Atelier with The Balcony (Figure 4), we see that Manet tries a variation by moving the Second (the smoker in Breakfast) up front and moving the Third (the boy) in the middle ground. The effect is that now all gazes are oriented in different directions out of the picture.

This creates a great tension which is then tamed and contained by the geometrical order of the railing, the shades, and the black square.

To complete the scheme in The Balcony, the boy is looking as the “Other” from the back, although the dark background makes him almost invisible (easier to see in the original than in most reproductions). The flowerpot and the dog stand in for the “still life” (Lemon) in the foreground.

There are now (at least) two different interpretations on what is happening here:

One interpretation, for instance by Dombrowski (2010), argues that the underlying theme is the dynamic between private and public sphere.

The figures are stepping out into the public sphere – on the balcony – and keep their private sphere literally in the dark – the room behind them. They step out to participate, but they also protect their private life.

The relationship between individual privacy and influences of the public market and state was ardently debated at the time, as Dombrowski shows. Visualizing the precarious situation between private and public spheres by floating the figures in a semi-public space on a balcony might, in fact, have motivated Manet who was politically very engaged if not active.

The theme of the public sphere, especially the marketplace out there in the street, was introduced into Manet’s scheme already in connection with the different types of gazes (Post 16: Manet and Emotions). Berthe Morisot is clearly fascinated by some public event in the street.

I will come back to this interpretation in the next post.

Another interpretation keeps the focus on the relation of Manet and Morisot.

As indicated in Figure 3, there is a strong attraction between Manet, the painter, and Morisot, the model. (Brombert is seeing a small smile on Morisot’s face reminding us of the knowing smile of the model Victorine in the Luncheon.)

Manet is placing Morisot on frontstage for very personal reasons, and, tellingly, he paints the faces of the other two persons less defined. (Fanny Clauss, modelling the other woman, apparently was somewhat irritated by that.) He even turns Morisot’s face a little more toward the front – toward him – as would be afforded by the scheme.

Manet is interested in Morisot not only as a painter who indifferently organizes elements of composition in pictorial space, as Georges Bataille points out. Or in his words: he is not only composing the “underlying unity of insignificant things” (p.91). Manet realizes already in this first encounter with Berthe that he is looking not only at an object of his gaze as a painter, but at a person he desires and values; and he is looking at a subject that is gazing back as a person who is attracted to him.

Or in the words of Nancy Locke (2001, p.154)):

Manet sees “Berthe’s gaze as an artist rather than an object”, and as a “distinctive subjectival presence”. So, in the portraits of Berthe in the following years:

“Manet explored the very nature of subjecthood, of what might constitute ‘self’ and ‘other’.”

We see in the portrait of Morisot by another female artist (Figure 3) that Morisot is claiming in her gaze to be recognized as a person – and not only as a woman by an attractive male painter.

The problem is that this loving interaction between painter and model does not fair well with applying a formal scheme to the object of painting.

Locke cites Sartre: “By the mere appearance of the Other, I am put in the position of passing judgement on myself as on an object, for it is as an object that I appear to the Other” (p.171).

In Manet’s scheme the Other is already included as the alternative view (“Other”) on the object of painting and as a reflective view on himself positioning him as painter in the art tradition (“Big Other”). Now Manet becomes aware that the object looking back as a subject on him as a subject adds another level or depth to his understanding of self and other.

Berthe’s view is not just like any other view, it is a view privileged by their mutual recognition as persons with an own identity to be respected and reflected in the painting.

Painting his view of her requires a reflection of her view of him.

Painting with sincerity means not to arrange “insignificant things” (Bataille) anymore, but to do justice to a very significant relationship with implications for the conception of the painter’s own self.

Locke identifies the problem specifically between Manet and Morisot and explicitly not with Victorine Meurent. But we encountered already a similar problem in Olympia.

In that case, MyManet assumed that the strong gaze of Olympia – insisting on her dignity – was partly enforced by the attitude of the model Victorine opposing her perception as a prostitute.

As a counterweight, Manet introduced the black cat.

On the level of design, this saved the balance of the picture and realized Manet’s scheme;

on the level of content, the expressive cat served to unsettle the viewer making him or her aware of the underlying dynamics between painter and model, painted figures and viewer.

Thus, the depth of reflection can be integrated into Manet’s scheme and handled with painterly means. But the complexity of the painter-model relationship certainly increases the complexity of any solution aspiring to sincerity.

In The Balcony, the problem is demonstrated by the strong geometrical frame taming the tensions and by the reaction of the other model, Fanny Clauss, who did not appreciate her role in the painting.

It seems – to avoid the issue – Manet decided to paint Morisot without the scheme in a series of portraits, to explore seeing the world through her impressionist eyes without her in the picture, and – looking at her looking back – to develop a “feminine gaze” (Locke) on other women and himself.

Besides, he chose other topics outside the scheme (portraits, still lives, sea views, landscapes) waiting for the occasion to apply his scheme again.

And we should not forget that in 1870/71 France was at war with Germany – but more on that in the next post.

After Morisot’s marriage, the issue was solved – at least, their relationship was recast in an entirely different set of social norms which prevented Morisot from modelling for him – and Manet started another phase in his painting.

I promised to return to the first interpretation, the theme of private versus public sphere in The Balcony.

For this purpose, we will take a closer look at the most political painting among Manet’s major works, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico (1867). It is – like Olympia – not a clear case for Manet’s scheme, but it demonstrates how Manet confronts the problem of power in his work.

And Yes! Visiting the Museum D’Orsay I certainly also saw the Luncheon on the Grass again!!!

See you in two weeks again!