– about My Manet

– about Your Manet.

To read from the start

click “Go to Post 1”

To look for topics on Manet,

go to List of Posts below.

For an introduction,

go to Overview below.

I want to encourage you to comment!

Read more on the project in About

and in “Installation My Manet”.

List of Posts:

Post 1 Painting the activity of painting

Post 2 Manet and the puppet theatre

Post 3 On “Facingness”

and Social Scale in Manet

Post 4 Faces in Velazquez and Manet

Post 5 System of Faces and Gazes

Post 6 Beyond the Viewer:

Who is looking?

Post 7 The Emergence of

Manet’s Scheme

Post 8 The Composition

of Luncheon on the Grass

Post 9 Manet’s Scheme:

Composition in Social Space

Post 10 Manet’s Realism

Post 11 Manet, Baudelaire,

and realistic Formalism

Post 12 Manet’s Self-Portraits

– Seeing Oneself Seeing

Post 13 My Manet – looking back

and looking forward

Post 14 Manet Painting Christ

Post 15 Painting Christ

– Another Self-Portrait?

Post 16 Manet and Emotions

Post 17 On painting a modern nude

– Manet’s Olympia

Post 18 Manet’s Enigma

– Breakfast in the Atelier

Post 19 More on Manet’s Enigma

– Breakfast in the Atelier

Post 20 On Manet’s Balcony

Post 21 Manet and Political Power

Post 22 On Paintings, Diagrams

and Exhibitions

Post 23 More on Diagrams

and Paintings

Post 24 Seeing Being Seen

– Manet’s Perspectives

Post 25 Manet and the Mirror

– A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

Post 26 Manet’s Scheme in the Mirror

Post 27 Manet and the Male Gaze

Post 28 Manet’s Theatre: Painting “On Stage”

Introduction and Overview:

In my view,

Manet aims to paint the activity of painting in Luncheon on the Grass.

He does this not directly by showing himself as painting in the painting, but he paints in a way that the painting is personally addressing and engaging the viewer.

It leads the viewer to think about what is happening before his or her eyes.

This “happening” I want to analyse

– first in 7 questions and 7 answers posed in “Installation My Manet”.

Then, we will go beyond to other paintings.

Post 1

will tell more about the implications of this view.

Sitting in front of an easel with a brush in your hand, an empty canvas before you, and perhaps a model inspiring you, is a social activity.

The painting of painting – in my view and supposedly in Manet’s view – assumes at least two people, the painter and the viewer, and – typical for Manet – the model as a third person. The painter is his or her “own first viewer” and the other persons may not always be present, but the activity nonetheless is a (virtual) interaction.

This implies a certain scale of the scene within the painting:

At least two persons communicating with each other face-to-face and in a certain setting,

typically in the atelier.

Thus, still lives, larger crowds of people, and landscapes will raise different questions. We might decide to look at them later.

Manet depicts this in Figure 1 in a social scene – with a painter looking pretty much like Velasquez.

We know that Manet loved this studio situation and immersed totally in the activity!

In Post 2 and 3, a model or paradigm for Manet’s view – the puppet theatre – is described.

Manet puts the social activity “on stage”.

Starting with Post 4 and 5,

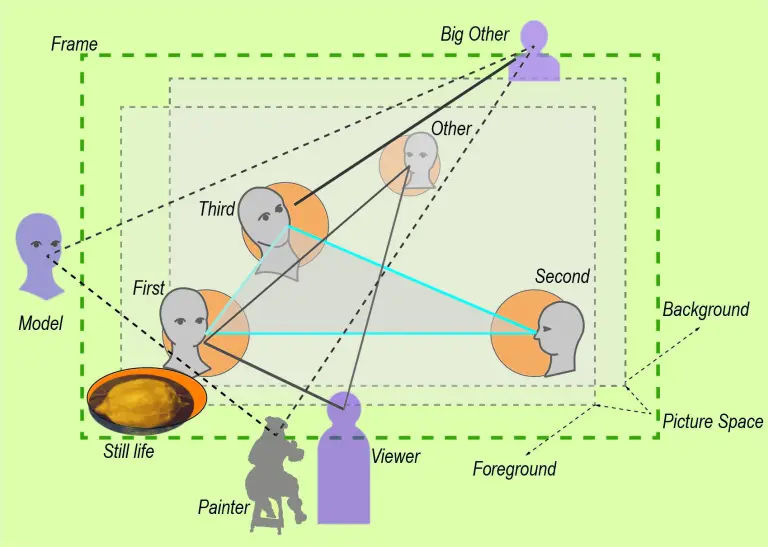

we will introduce the diagrams which I will use to visualize what Manet was thinking

– or what I suggest he was thinking.

The starting point are paintings by Diego Velasquez.

We know that Manet admired Velasquez as perhaps the greatest painter ever!

The diagrams introduce the actors on the “stage”.

Then, in Post 6,

I will look at painting as a “social form” and reaching beyond the stage into the atelier.

We don’t need any theory to realize that the interaction in the atelier assumes that persons will play certain roles or fulfil certain functions.

Actually, this is shown in a painting by Gustave Courbet on “The Allegory of Painting”.

We will have a look at it.

We know that Manet considered Courbet as a rival for the title of the “true realist”,

and he knew this painting!

In Post 7, we see the emergence of Manet’s scheme.

I will elaborate more on the steps Manet takes to develop a scheme guiding the selection of perspectives and roles in his painting of painting.

He reduces the complexity of the situation by deleting “unnecessary” personnel.

This can be inferred by looking at two paintings he produces just before embarking on the Luncheon in the Grass.

The following Post 8 and 9,

will finally take a closer look at the Luncheon on the Grass itself.

Since this is one of the most frequently interpreted paintings in art history, we might expect that nothing new can be said about it.

But it speaks for the greatness of this painting that even some 160 years later it inspires new views – also by other viewers – and we will have a fresh look, too.

The result will be the “formal scheme” of Manet’s figurative paintings!

In Post 10 and 11,

I will say more about Manet’s “realism”. Comparing his innovative approach to other painters of his time, we might think that he actually is less “realistic” than, say, Courbet, Corot, or the early Degas. And then, Impressionism is seen as a kind of new realism, but Manet is – not only in my view – not an impressionist.

So, what is Manet’s realism? In the perspective of science, we may say that Manet creates “reasoned imaginations“.

His position is a “realistic formalism” and I will try to explain this also by comparing his view to the realism of his friend, the novelist and critic Charles Baudelaire.

In my view, the paradigm of a “Puppet Theatre” or Marionette Theatre helps to understand how Manet sees the social reality of painting similar to the reality on stage.

This is what the little installation or collage, presented at the end of “Installation My Manet”, tries to capture.

In Post 12,

we return to Manet’s self-portrait which is shown at the beginning of the installation.

I have postponed the discussion, because it is better understood as a later application (1879) of the “formal scheme”.

From there, we will go on beyond the installation.

The puzzle – why my fascination with the painting – is only partly solved.

Many may be fascinated, but why me?

And the claim that this “formal scheme” applies also to other famous paintings of Manet has to be documented and discussed. So, we take a look at The Breakfast in the Atelier, The Balcony, Christ mocked, and more

… including the unlikely cases of Olympia and

A Bar at the Folies-Bergére.

And, hopefully, there will be other questions waiting to be answered

– raised by Your Manet …

Leave a Reply