Installation at the Exhibition “Boundless” of the Järvenpää Art Society, January 2021

Text introducing the concept of the installation

My Manet

My view of Manet in 7 questions and 7 answers

Richard Pieper

About the project:

My Manet is a project about the hidden meaning in Manet’s painting Luncheon in the Grass (1863) (1)

It is the first great masterpiece of Edouard Manet (1832-1883)

and regarded as one of the starting points of modern art.

It has triggered a wealth of interpretations until today.

MY Manet is my personal view, but I hope it inspires you to look again with your own eyes…

Manet did not write about his art, he preferred to paint. Here, I take the view of the painter speaking on his behalf.

I try to visualize in diagrams seven questions and answers he might have given himself.

Imagine:

Manet himself is talking to you around 1863 when he is thinking about Luncheon in the Grass.

Comments are added by me from about 160 years later…

Numbers (N) in the text refer to paintings and diagrams.

A list of paintings with more information and a selected bibliography is available at the end.

For a copy of the text, please, contact the author.

Question 1: How can I paint the activity of painting in a modern way

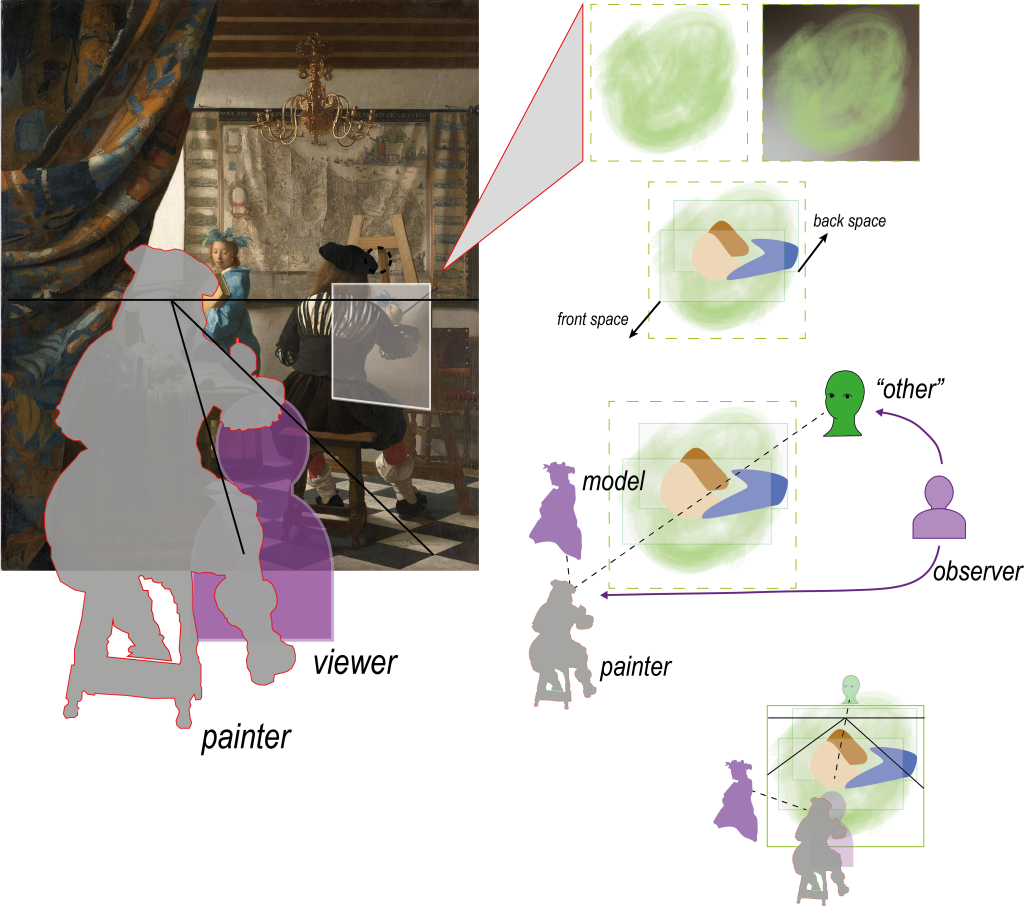

Take the example of Jan Vermeer (1632-1675) The Art of Painting (1665): (2)

Vermeer shows a painter and his model. (3)

He assumes a viewer in front of the painting and himself as painter behind the viewer.

Notice the curtain separating the activity of painting from the painter (Vermeer).

But the painting of a painting happens on the canvas in the painting! Why duplicate painter and model?

A painter starts on a white canvas – and the first paint already creates a visual space with depth.

(With a dark canvas, the space appears to emerge from a mysterious background. A “realistic” painter prefers painting in fresh colours “on this side” of the canvas – unless mystery is intended.)

Vermeer shows an unfinished painting to indicate the ongoing process.

Why not show the whole painting as unfinished – more like a sketch to be completed by imagination?

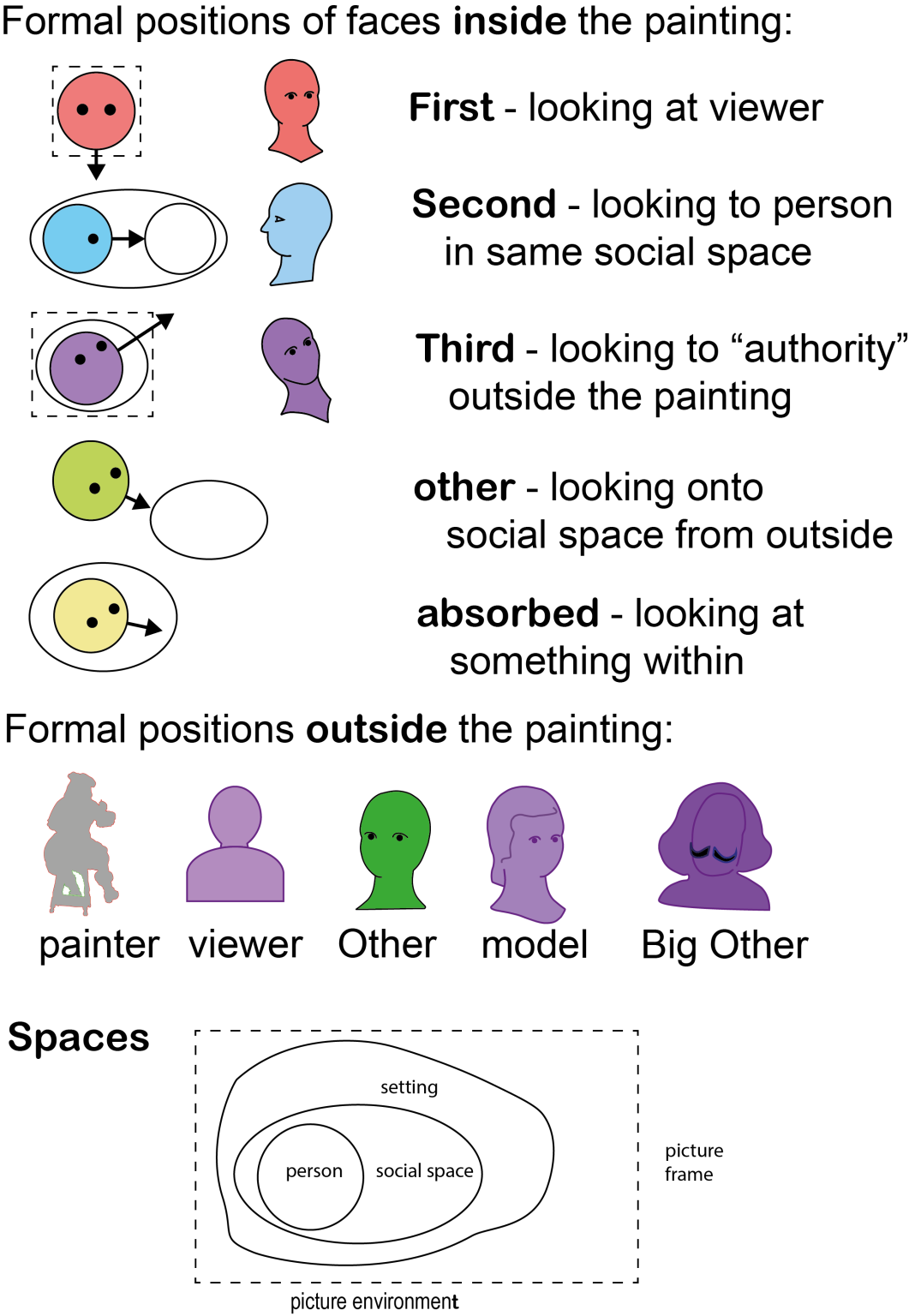

Shapes will occupy an own space defining front and back – and faces or figures will define this space as a social space.

The social space will be created by their gazes including people not directly shown in the painting.

That is how we experience social spaces: we follow the gazes.

Why not include the painter and the viewer in their social space. Why not show the painting of a painting from their view?

The setting suggests that there are people inside the painting and outside the painting – the painter in front and the model in view to the left.

The setting could be seen from the “other side”.

We may imagine the viewer/observer moving around and taking the positions of others including the people inside.

Vermeer uses the system of perspective to organize his painting – which exactly fixes the viewer and the double painter in front in a powerful position.

Why not let the gazes of figures do the organizing in a more flexible way?

Why not show the painting of painting as a communication between figures inside and outside?

How?

Answer:

Show painting as an act of painting in a virtual social setting

where people inside the painting communicate freely with people outside the painting.

That is the modern life!

Comment:

The answer means that the painting creates a virtual installation engaging positions outside the painting.

The physical space of perspective is substituted by a social space created by the gazes of persons.

For Manet, the complete setting is typically his atelier with his best friends visiting almost daily.

For Manet, the still life and the landscape are special cases, because they engage the viewer’s attention without “looking out”. The portrait is a limiting case, because it “looks out” without communication within the painting.

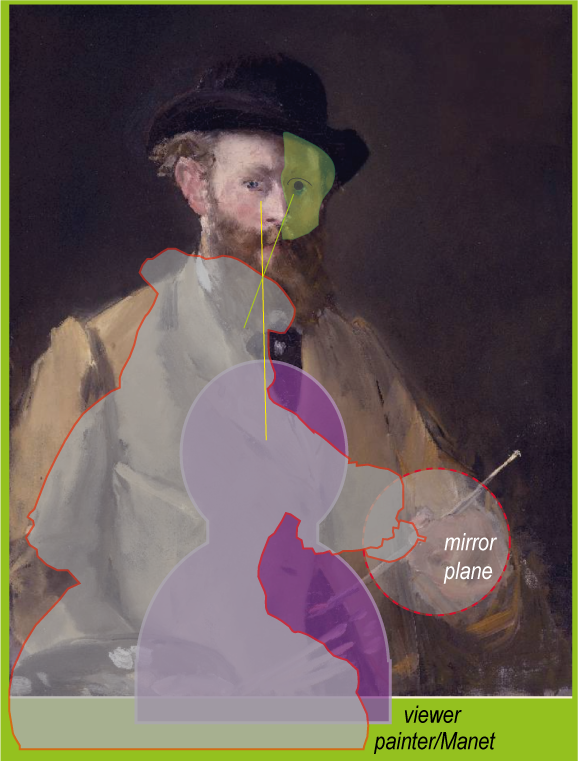

Interesting special case: The self-portrait of Manet. (4 and 5)

Here we see “two Manets” – the painted Manet and the painting Manet (green) looking from “behind”.

Note: the gloomy dark background – in 1979 Manet was already suffering from a disease killing him four years later!

Question 2: How can I show views communicating into and out of the painting?

Take three examples of my (Manet’s) favourite painter Diego Velasquez (1599-1660):

Example 1: The Little Cavaliers (Manet’s copy 1859 of Velasquez’ Conversing Gentlemen) (6)

Persons are grouped in social spaces; they look toward the viewer (red), toward each other (blue); to other groups (green); absorbed in their group (yellow); or out of the painting/frame (purple).

Example 2: The Drinkers (or: Feast of Bacchus) (7)

The central figure Bacchus seems to look out to a “higher authority” (a god? to Velasquez?), not to the viewer or the painter. Three onlookers (green) are looking at the central group.

Example 3: Las Meninas (detail) (Manet’s favourite painting!) (8)

In the centre and engaging the viewer, we see the daughter of the King and Queen. They are reflected in the mirror behind on the wall. They are entering the room in front and looking indirectly at the painting from the back. They are the “higher authority” we cannot see.

Velasquez himself is looking out at the royalty, his authority – not at the viewer?

In the background, we see a perfect version of the onlooking “other” (the royal master of ceremony) shown within the painting like the painter himself.

Answer: Show gazes from inside the painting to implied person(s) outside the painting.

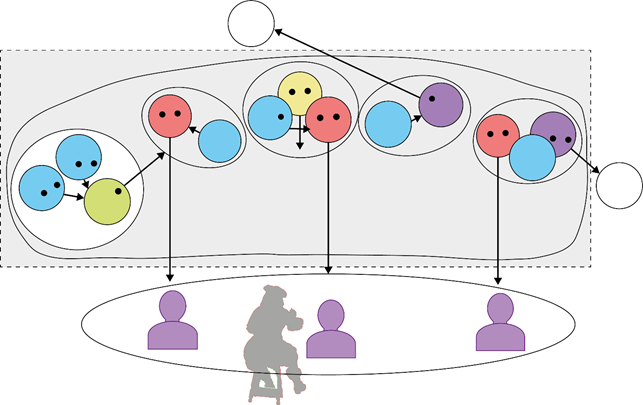

Question 3: How many gazes or persons are needed as a minimum?

A painter should aim for simplicity – concentrate on essential elements.

Answer: Looking at the diagrams, we see (9)

5 positions within the painting

5 positions outside the painting

or 4 without the non-communicating absorbed position

or 3 when counting painter and model separately on another plane/layer

3 layers – the person(s), the social space of groups, and the setting while the frame is transparent to a fourth layer outside the frame

These are the formal positions creating a social space within and around the painting. They are formal in the sense that they do not include any specific content of the communication or interaction of the persons presented or implied.

Question 4: What kind of social roles are involved outside the painting?

Take the example of Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) The Painter’s Studio – A Real Allegory (1855) (10)

Courbet wants the Allegory to show all the members of society relevant for his realistic painting

which is happening in the centre – with himself in the centre!

To the left side:

members of society – his viewers – including the little boy with the cat

(the sitting man with the dogs may be Napoleon III)

To the right side:

members of the art community: friends, writers, artists, critics, art lovers/financers, etc.

(reading a book and not interested: Baudelaire, the realist writer and Manet’s friend)

Really interested and looking at Courbet painting are only

the viewing boy and the model next to the painter (red circled in centre),

an art critical woman at the right (red circled),

an old Rabbi or philosopher at the left edge (red circled)

The others seem to be just there to support the grand Ego of Courbet.

Answer: We need the following social roles:

the painter

the model

the viewer

the critic

the “authority”

who is “free” and skilled to transform ideas with paint into a visual object

who visualizes a referent for the painter in a realistic setting

who experiences the visual object as a painting from “front”

who represents the “other” taking another perspective from the “back”

who represents art as a cultural tradition or institution from “above”

Comment:

Formal social roles in this spirit are conceived by Georg Simmel (1858-1918), a founder of modern sociology and philosopher of art, fashion, and modern life.

His Metropolis and Mental Life is cited by art historians trying to understand Manet as painter of modern life (T.J. Clark 1984).

The model has a crucial role, because for Manet she has an active role in painting as a social process.

Therefore, Manet has preferred models interested in his art (family members, supporters) and artists like his favourite model Victorine Meurent or his friend Berthe Morrisot.

The painter is his own first viewer, but Manet is aware that a painting has to draw attention to be “seen” and that ideas have to be “seen in” the painting by understanding viewers to become real cultural objects.

The painter is foremost his own critic, but he develops his self-critical capacities in a discourse with others. Manet is well aware of the social aspect of creating art and maintained close friendships with other artists.

Manet valued highly the tradition of art and sought the recognition by art institutions. He initiated a “revolution” in art, but only because he believed that existing art institutions were not promoting an art expressing the experience of modern life, and he participated in creating new institutions.

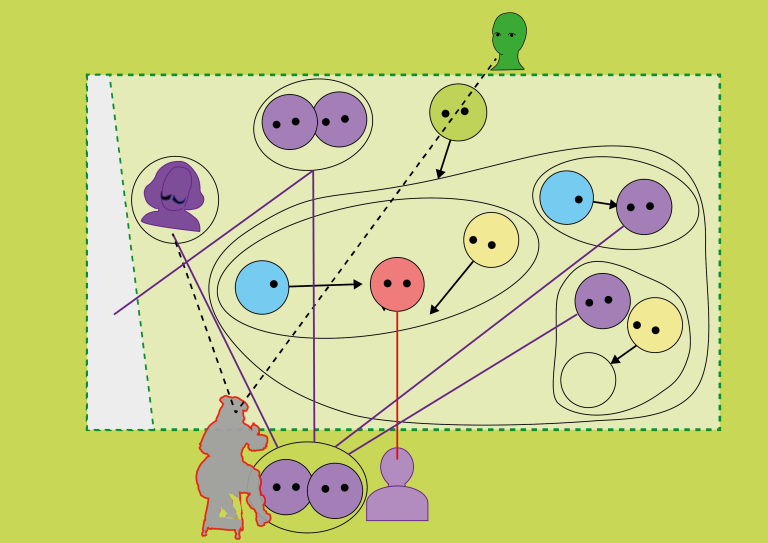

Question 5: How can Velasquez and Courbet be combined in a social scheme?

Let us take the social roles from Courbet and apply them in a painting in a “Spanish Style” like suggested by my friend Baudelaire.

Comment:

There are sources from other painters involved as art historians have discovered (Fried 1996).

But for present purposes the examples above are sufficient to see the emerging scheme.

Example: The Old Musician Manet (1862) (11)

The elements from Courbet are placed around the painting – see diagram.

The central part is mirrored to support the following interpretation. (12)

We see

- a group of three (First, Second and Third) in the middle

- a girl – inspired by the boy? – looking on from the left like another viewer

- a figure (The Absynthe Drinker from Manet’s own painting 1859) looking on from the back

- a figure of the “higher authority” cut off by the right frame

- a little still life marking the front (typical for Manet)

Answer: OK, a first try – not really following the principle of simplicity, but getting close:

- the girl is not really needed (either a second viewer or a second onlooker)

- the boy with white shirt (Third) is looking out, ok, but not toward the “authority”

- the drinker has no clear role – just standing around

- the old man really should get out of the painting…

Let us try again…

Question 6: How can I paint a female nude following the emerging formal scheme?

My friend Antonine Proust has suggested to paint a female nude for the next exhibition while we were walking along the river and looking at the girls…

Comment: In contemporary exhibitions of the French Academy of Fine Arts, there were hundreds of paintings with nude females – all “disguised” as mystical, historical figures or goddesses, but no nude female of modern society.

The scandal created by Manet’s painting was not caused by the nudity of the female. Rather, a contemporary female appearing nude in a painting (together with two dressed men!) had to be a prostitute or “loose woman” and that violated social norms and norms of “high art”.

This issue of interpretation, we will not take up here in My Manet; it belongs more to another painting Olympia which turns out to be an interesting variation of the scheme.

Answer: See The Luncheon in the Grass by Manet (1863) !

This needs some explanation:

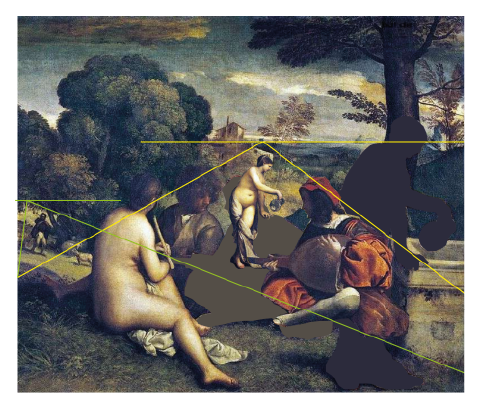

There was in the Louvre museum (still is) a painting by Titian Pastoral Concert (1508). (13)

This painting is the base.

But:

The figures communicate only with each other – not to positions outside.

However:

With a little modification, we get the basic composition with two different perspectives. (14)(15)

Next, we need to change the gazes to correspond to the scheme.

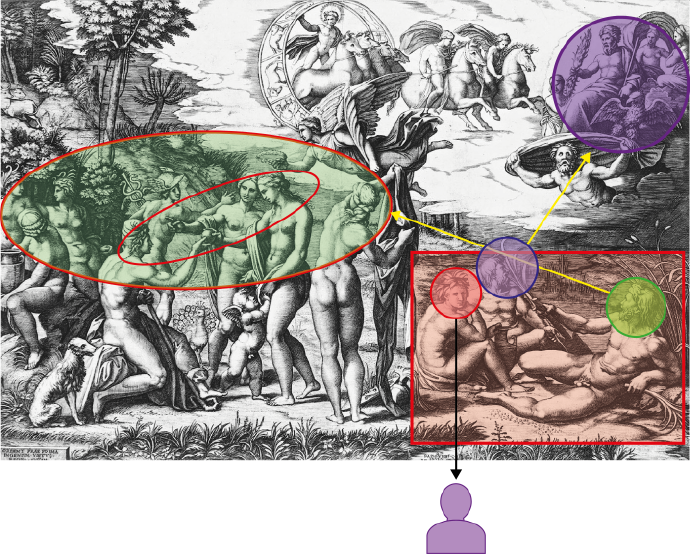

There is an etching by Raimondi of a painting by Raphael Judgement of Paris (ca. 1475). (16)

Very fitting theme: Paris (the guy in the left group) is judging the beauty of Venus (in front of him).

Jupiter (the “higher authority”) is already approaching (from the upper right corner) to confirm that the judgement of Paris is following authorized values of beauty.

The group in the lower right corner are a perfect example of the scheme!

This we can use to develop the final scheme!

Comment:

Important is the view of the Third in the etching. He is looking at the “higher authority” of Jupiter,

here representing the value of beauty in art!

Jupiter is flying in from the upper right corner like the balloon in another of Manet’s painting – see below.

Question 7: What happens to Realism while using an abstract formal scheme?

Comment:

Manet always considered himself to be a realistic painter, painting what was in front of his eyes. However, he typically created or at least finished his works in the reality of his studio. Most of his paintings somehow feel arranged or “staged”, even when they depict modern life.

Manet’s group of friends – artists and writers like Baudelaire, Champfleury, Duranty, Zola – are all part of the New Realism in contemporary art in France, and critics of the still dominant Historicism and Romanticism (and of the naturalistic realism of Gustave Courbet).

Charles Baudelaire writes with Manet in mind:

“As a painter I am called upon to look hard at the faces that cross my path, and you know the delight we take in this faculty of ours which, in our eyes, makes life more alive and more meaningful than it is for other men.” (cited from George Bataille Manet (p. 18, 1955)

Manet’s Realism follows principles of simplicity, sincerity, and naivety in experience and painting:

simplicity: focus on essential elements and relations, not on surface and appearance

sincerity: follow intuitions of values like truth and beauty in art

naivety: keep an open-minded curiosity for modern everyday life – like children

Engage with every painting and with every subject like it is the first time!

Manet’s reality of painting is based on

the situation in his atelier (17)

the painting material, colours, brushes, canvases

the model, costumes and objects

the paintings around him

visiting friends like the poets Baudelaire, Zola and Mallarme; his wife and son.

the environment of Paris

with its urban life in cafes and on the boulevards,

with people dressed in the latest fashion (including himself),

discussing life, politics, and philosophies with a good beer at hand.

the realities of modern technology

like photography, ships and trains, and the World Fair with balloons in the air.

One is tempted to think that the man (Third) in Luncheon in the Grass is actually looking at the balloon designed by Manet’s friend Nadar

– as a symbol of modern culture, the balloon appears in several drawings and in his painting of the World Fair (1867).

most important:

the social reality created by gazes of people!

Example:

The woman in Luncheon in the Grass is playing a double role (indicated by 2 perspectives):

looking as a liberated modern woman at the viewer

and

looking as the model Victorine with amusement at Manet daring to paint a modern nude!

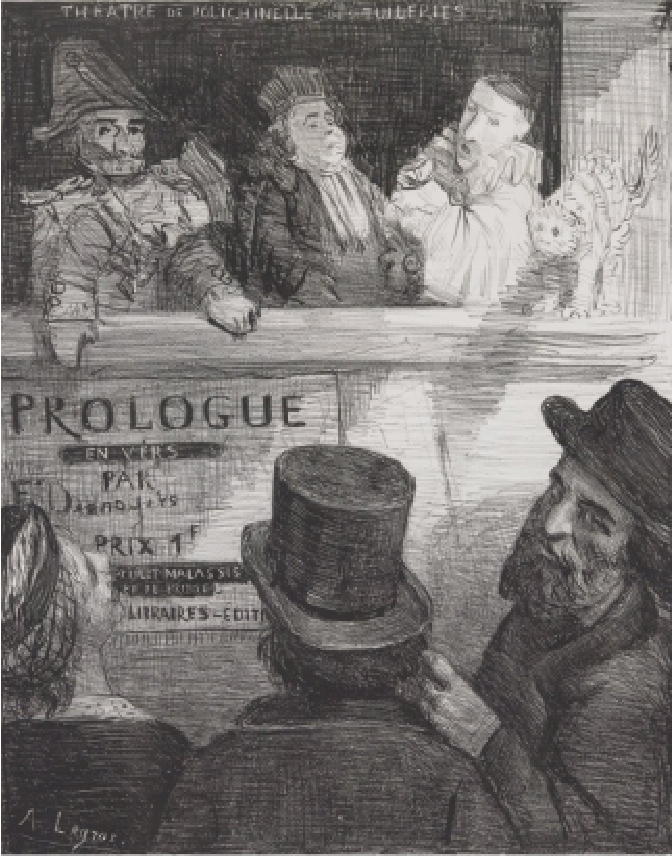

Manet’s paradigm for painting is the puppet theatre or marionette theatre.

Here is why:

At the time of his breakthrough – around 1862-1863 – Manet was engaged in the venture of his friend, Edmond Duranty, creating a new and realistic puppet theatre, and Manet designed posters for it.

The puppet theatre stands for a realistic culture for everybody; the performances happened in public parks like the Tuileries.

At the time, Manet made a painting Music at the Tuileries including all his friends.

Engaging the people is vital for the puppet theatre; the stories and their morals are simple; the visual spectacle is important;

the roles – like Polichinelle (Punch)– are pre-configured and simple.

Actually, we can see the primary roles of Manet’s scheme in the etching by his friend, Alphonse Legros (1861). (18)

The puppet theatre happens on a narrow stage, with arms and legs of the puppets often reaching out to the viewers, “still lives” marking the front of the stage, and curtains closing the stage to the back.

Manet creates in his paintings a narrow picture space like a stage.

In Luncheon in the Grass, this narrow space is created by drawing the woman in the back too large moving her visually further to the front! (19)

The puppet theatre is an installation including the audience and the public space.

In his etching of the stage, Manet (in disguise of a puppet) looks through the curtains from backstage

– as the “other”.

The contemporary discussion about the art of operating puppets emphasizes the graze and simplicity of their movements.

Puppets are seen as expressing the deeper reality of character and motion.

What is interpreted often as a strange lack of life and expression in Manet’s figures

is the moment showing the puppets about to stage a yet untold story

which the viewer is invited to create by engaging with an open painting.

That is why I put

Luncheon on the Grass on the stage of a puppet theatre! (20)

Then, I combined all the ideas above in a general scheme for painting Luncheon in the Grass (21)

and I presented My Manet as an installation

at the exhibition “Boundless” of the Järvenpää Art Society, January 2021.

Final comments:

My Manet does not question other interpretations – it adds an own view.

Frequently, interpretations take the view of the viewer and offer a contextualization, for example:

How can we explain the scandal caused by the painting in view of contemporary societal norms?

How does his personal “family drama” (his son being perhaps his father’s son?) influence his art?

How does Manet’s “revolution” of art reflect political revolutions, emerging capitalism, and modernization?

How do contemporary gender relations influence his way of painting females?

My Manet takes the view of the painter:

Manet is developing a creative, formal scheme for painting people

by using the natural way of people organizing their experience of other people in a social setting

– including himself as the painter and the setting of painting.

And he wants to be “only a painter” and not compete with his literary friends in “telling stories”.

This may help to answer another question:

Why did Picasso devote more than 200 paintings and studies to this painting? More than to any other painting by another painter? Perhaps, because he also searched for ways to escape the limitations of the canvas by creating virtual spaces reaching beyond the painting.

Final Question: Does Manet apply this scheme in all of his paintings?

Answer: No

Manet uses also other schemes of composition, but many of his most famous paintings can be seen as applying variations of the scheme

– including The Balcony, The Breakfast, and his final masterpiece A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882).

But this is another upcoming part of this project….

References

On Edouard Manet:

Brombert, B.A. (1996), Edouard Manet. Rebel in a Frock Coat, University of Chicago Press

Clark, T.J. (1999), The Painting of Modern Life. Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers (revised edition),

Princeton University Press

Dolan, T. (ed.)( 2016), Perspectives on Manet, London: Routledge

Fried, M. (1996), Manet’s Modernism, or, The Face of Painting in the 1860s, University of Chicago Press

Hanson, A.C. (1977), Manet and the Modern Tradition, Yale University Press

Hopp, G. (1968), Edouard Manet. Farbe und Bildgestalt, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter

Lüthy, M. (2003), Bild und Blick in Manets Malerei, Berlin: Gbr. Mann Verlag

Tucker, P.H. (ed.)(1998), Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, Cambridge University Press

Other references:

Oackley, T. (2009), From Attention to Meaning: Explorations in semiotics, linguistics, and rhetoric, Bern: Peter Lang AG

Rebentisch, J. (2012), Aesthetics of Installation Art, Berlin: Sternberg Press

Simmel, G. (1971), The Metropolis and Mental Life (1903), in: On Individuality and Social Forms. Selected Writings (edited by Donald N. Levine), University of Chicago Press

Pictures and sources:

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass (1863): Masters of Art – Edouard Manet, Kindle edition, Hastings: Delphi Classics, 2016

Edouard Manet, The Little Cavaliers (after Velasquez) (1859): Masters of Art – Edouard Manet, Kindle edition, Hastings: Delphi Classics, 2016

Edouard Manet, The Old Musician (1861): Masters of Art – Edouard Manet, Kindle edition, Hastings: Delphi Classics, 2016

Edouard Manet, Self Portrait with Palette (1879), Masters of Art – Edouard Manet, Kindle edition, Hastings: Delphi Classics, 2016

Edouard Manet, Guérin’s Deuxième Essai de frontispiece, etching (1861): S.P. Avery Collection, New York Public Library, Public Domain

Johannes Vermeer, The Art of Painting (1668): Wikipedia Public Domain

Diego Velasquez, The Drinkers (The Triumph of Bacchus) (1629): Wikipedia Public Domain

Diego Velasquez, Las Meninas (1656): Wikipedia Public Domain

Gustave Courbet, The Artist’s Studio. A Real Allegory (1855): Wikipedia Public Domain

Giorgione, Pastoral Concert (1509) (now attributed to Titian): Wikipedia Public Domain

Marcantonio Raimondi, Judgement of Paris (after Raphael) (1525): Wikipedia Public Domain

Alphonse Legros, Frontispiece etching to Fernand Desnoyers, The Théâtre de Polichinelle (1861): Paris, cliché Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Public Domain

Alphonse Legros, Le Théâtre de Polichinelle des Tuileries, lithograph: Paris, cliché Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Public Domain