Manet considered himself to be a realistic painter – but what is a realistic painter?

Even worse, there were (and are) different versions of realism.

Courbet saw himself – and critics admired him – as the most prominent realist painter of his time, initiating the realist movement after the 1848 French revolution.

But Manet, a decade younger, distanced his art (and himself personally by keeping away from Courbet’s circles) from Courbet’s naturalism.

Novelists like Baudelaire and Zola initiated a new realism in literature and poetry, but it seems that Manet never agreed with their interpretation of his art.

And then, there is the final question of “Installation My Manet”:

Question 7: What happens to Realism while using an abstract formal scheme?

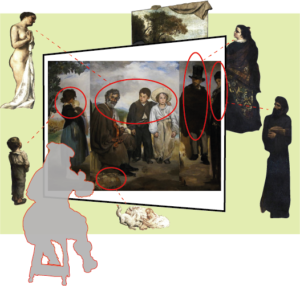

As the caricature by Honoré Daumier suggests, a “Battle of Schools – Realism versus Classic Idealism” was waged already before Manet created his version of realism.

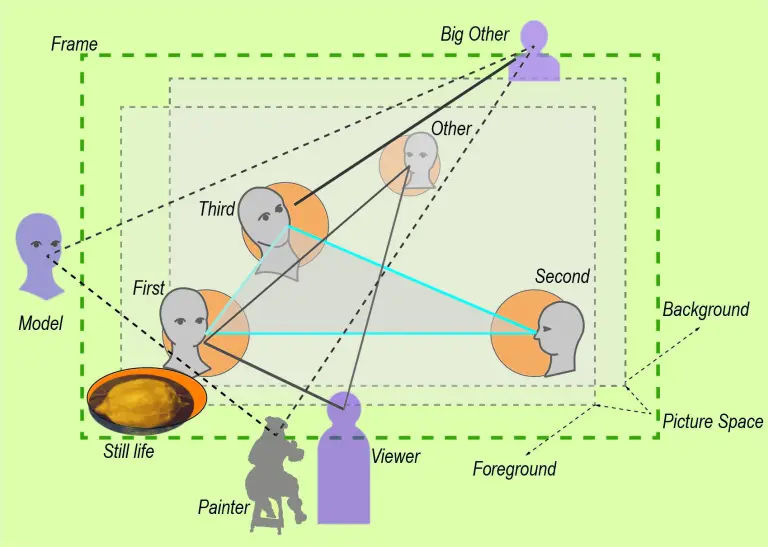

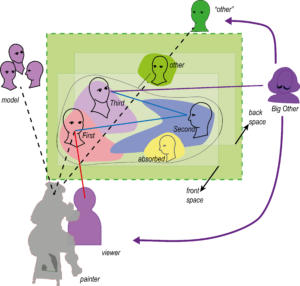

Figure 1: Battle of Schools – Realism versus Classic Idealism

by Honoré Daumier (1855)

In this battle, the realists developed new styles of painting in opposition to traditional academic conventions,

choosing topics from modern life and contemporary landscapes rather than from history and mythology,

and siding with the political goals of workers and peasants in the new republic.

The philosopher and anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon – Courbet’s friend whom he portrayed – is quoted as saying: “Any figure, whether beautiful or ugly, can fulfil the ends of art”

and the poet Desnoyers added (cited in Rewald 1961, p. 28):

“Realism, without being a defence of the ugly or evil, has the right to show what exists and what one sees.”

Manet – himself from the upper middle class – supported all his life the republican cause, although the political revolutions and wars of his time (Manet is a contemporary of Karl Marx) are reflected only in few of his works.

As mentioned before, his friend Edmond Duranty revitalized the tradition of puppet theatre in the early 1860ies with realism as a framework for art, public education, and entertainment.

Realism, thus, had a distinct ethical and political dimension.

Unfortunately, Manet never articulated his own understanding of realism, so we rely on his pictures to reconstruct his concept of realistic painting.

To make things even more complicated, his painter friends and followers – Frederic Bazille, Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and others – developed into the school of impressionism.

They saw him as their mentor and leader, but Manet never called himself an impressionist and did not exhibit with the impressionists.

In art history, however, at least since John Rewald’s The History of Impressionism (1946), Manet is usually regarded as an impressionist or at least as bridging between realism and impressionism. Impressionism is seen as the new stage of realism based on scientific insights: on the rapidly growing disciplines of physiology and psychology and their application to understanding modern urban life and the nature of visual experience.

Robert Herbert (1988, p.33) counts Manet among the impressionists and both under naturalism, since Manet like the others paints his impressions of Parisian life.

Michael Lüthy (2003, p.73ff) rejects this view and insists that Manet is not an impressionist and misunderstood as realist, at least in the sense of naturalism.

So, what is Manet’s realism and how does it differ from impressionism?

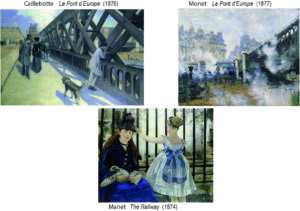

After all, there is a world of differences between Gustave Caillebotte and Claude Monet (for a comparison: Herbert 1988, p.20-32). Does Manet fit somewhere in between?

Figure 2: What is realism? Comparing Caillebotte, Monet and Manet

Interestingly, I found the most convincing argument not by art historians (not yet?) but in the history of the philosophy of science. Here, Daston and Galison (2007) researched the meaning of the concept of objectivity in natural science since about 1600 – the time of Diego Velazquez.

Their examples are visualizations of natural objects for research purposes. Natural scientists and artists were cooperating in depicting objects like botanic plants, animals, or the surface of the earth.

Their goal was truth-to-nature in drawing or etching objects like they really are, or naturalism.

From the start, they had the problem that in reality each object of a certain kind, say, an orchid or butterfly, was a little different from the other. There were accidental variations and the natural scientist had to advise the artist which deviations were relevant, and which were not.

Truth-to-nature did not mean to show an “ideal” flower; it simply meant that there is a general type which “exists” while variations just happen. Moreover, it was common practice to show the blossom and the fruits of a given flower on the same depicted plant, although this image could clearly not “exist” in reality.

Again, the scientist decided what to show and what not and the artist showed a “reasoned image” (p.42).

The image was objective because it showed what the scientist knew to “exist”.

If the artist got it wrong, these deviations were only subjective errors, as every knowledgeable person could “see”.

The terms of objectivity and subjectivity, in this sense, were introduced only later. (I recommend to read the fascinating story how the meaning in philosophy completely reversed!)

For our understanding of Manet, it is sufficient to recognize that this original meaning of “true-to-nature” persisted in the concept of naturalism in art.

While naturalism would only show what can be “seen”, realism would show what science claimed to “exist”.

But in science and philosophy things changed around the beginning of the 19th century:

subjectivity acquired the meaning of “existing according to theory” or “universal forms of experience”;

objectivity referred to “merely empirical sensations” or “merely objective nature”.

Thus, the meaning of the terms changed completely!

However, there was no basic problem with understanding that abstract schemes are realized in our subjective ways to perceive the world. Following the philosopher Immanuel Kant, we all use subjective schemata which enable us to “see” what “exists”.

Artists like Courbet could show what exists realistically, while scientist could rely on their senses observing phenomena and discovering theories.

But then, in the early 19th century, a number of developments interacted and shattered this view.

Political, economic, technological, and social revolutions – the transition to modernity – impacted on society.

An important effect was an increasing individualism supporting concepts of subjectivity linked to individual freedom and capacity to reason.

That was welcomed in art:

The transition lead to the idea of “art for art’s sake” or the autonomy of art, and to the expression of the artist’s freedom and subjectivity in art.

The effect in science was ambiguous. Enhanced subjectivity strengthened the scientific self, but it also resulted in increasing awareness of the ways subjectivity interfered with objective science. Especially, research in physiology and psychology demonstrated how researchers themselves were prone to misperceptions and bias.

“What exists” (objectively) and “what one sees” (subjectively) drifted conceptually apart!

In science,

methods were adopted which produced “objective images”, images as independent as possible from any interference by humans, both scientist and artists. The paradigmatic case is photography, which to some extent substituted the artist’s drawings and engravings. Objective procedures were introduced which, in effect, controlled scientific subjectivity by rational rigor on the level of observation, measurement, and visualization (“what one sees”) as well as on the level of theory construction (“what is known to exist”).

In art,

the new insights of physiology and psychology – research on the perception of light and colour, for instance – sparked a new awareness for the appearance of the world (“what one sees”), both in landscape painting and in the depiction of contemporary urban life. Impressionism, and later expressionism, can be understood in part as an exploitation of the results of this natural research, while, at the same time, claiming the full freedom for the expression of artistic subjectivity – Impressionism seen as new naturalism.

Both, Caillebotte with his exaggeration of perspective in modern urban planning and the presentation of fashionable people on the bridge, and Monet by showing the elusive play of light on the same bridge, will count as impressionists in this sense.

But what about Manet?

The railway bridge appears only at the right edge of the painting; a perspective into the picture is barred by an iron grill and hidden in white smoke, presumably from a passing train; in the centre and forefront, we find two people – a woman and and girl – who strangely command our attention, as we, the viewers, seem to have disturbed the woman reading . We are very close, but the woman is not really looking at us. The girl is holding on to an iron railing looking into the white smoke barring the background from view as the railing barres her (and us) from moving back toward the railroad. We are together “boxed in” in the foreground not really looking at each other and seeing little beyond the railing.

Unlike the scenes of Caillebotte and Monet, who present to us their subjective view of urban life, Manet’s scene is strangely “staged”. He makes the viewer “step back” to look at the scene more objectively by the tension created between spatial closeness and social distancing by the woman’s avoidance of a direct gaze.

Is this naturalism depicting a certain scene? Or impressionism of “what one sees”? Or realism of “what exists”? In what sense, is Manet the realist he claims to be?

Just as the concepts of objectivity and subjectivity have changed, the term realism changes and still changes – just think of modern hyperrealism.

So, we have to ask what the realistic concern was for Manet at the time.

He did not want to depict every detail. In the spirit of the tradition of drawing and engraving, he opted for simplicity and concentration on the essential elements with sincerity.

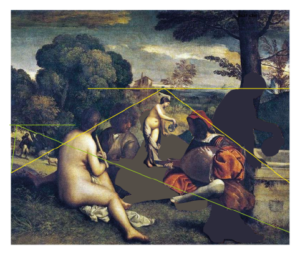

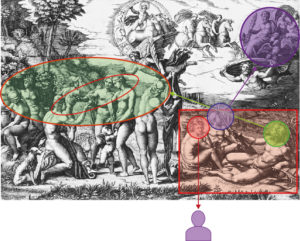

Manet practiced printing techniques himself and used extensively engravings rather than the originals of Old Masters as examples – like in Luncheon.

He extracted “structural elements” – as Lüthy describes it – and combined them in own compositions.

We have already identified some of these elements:

the narrow “stage”, the violation of perspective, the implication of a space before the painting by gazes toward the viewer, the flattening of figures and elements by direct light from the front eliminating modelling and shading, the arrangement of somewhat isolated elements and shapes, the collage character of the composition.

Realism in a narrow naturalistic sense presenting “what one sees” is clearly not his goal.

His realism aims at “what exists” but may not be “seen” readily:

Manet is focusing on “seeing others and being seen by others”, which in a social situation is a very real phenomenon!

The “structural elements” are elements of social forms which Manet presents just like the engravings in natural science, like combining the essential elements of a flower regardless of whether they can be observed in natural settings in exactly this way. His accent is on the more abstract forms which “exist” in a certain kind of situation rather then in the accidental aspects of “what one can see” in a specific case.

Manet creates “reasoned images” of painting as a social situation with interrelating gazes.

The figures and scenes appear somehow arrested, because Manet wants to capture them in an essential configuration, not in the fleeting, subjectively experienced moment characteristic for impressionism or in the accidental “freeze” of a photography producing “objective images untouched by human hands” but typically full of irrelevant elements.

So, Manet’s realism consists – in MyManet – on “showing what exists” in the situation of painting.

His special focus is on the configuration of real gazes and gestures relating persons. These configurations will change with the setting depicted, so we should expect variations in other paintings than Luncheon on the Grass – as the example of The Railway above shows.

The composition of the painting will not produce a naturalistic image of “what anyone can see”, but the composition of a “reasoned image” of essential elements incorporating insight into “what one knows”. Still, Manet is a realistic painter and not illustrating science. We have to come back to the difference between realism in art and in science.

At this point, I just want to link his realism again to the puppet theatre. As we have seen, the production of “reasoned images” required a close cooperation between the scientist and the artist. Unlike a theatre performance with writers, directors, and actors, each with their own agendas, the puppeteer is in command over the production. Like the scientist cooperates with the artist, the painter has, however, to cooperate with the model to sustain the social form he wants to present in the painting.

Therefore, it is not surprising

– that Manet had his quarrels with professional models and their “unrealistic” poses at the art academy,

– that he preferred to use the same models which were able and patient to realize a “reasoned imagination”,

and

– that he apparently had a great respect for his models and their dignity even if they were waitresses in a bar.

This social empathy he shared with Velazquez and it qualified him as a social leader of his own circle of painter friends.

(Feminist art historians have a lot of criticism for male artists (not only) of the time – like Courbet or Degas and their treatment of models – they are remarkably restrained in the case of Manet.)

“Reasoned images” are not merely formal compositions of abstract “structural elements”.

They claim to show reality or content of real life.

The new realism in literature of Baudelaire and Zola claims the same.

The puppet theatre makes the same claim.

We have to follow up on this aspect of content in Manet’s paintings.

So, see you next week!