There is a “male gaze” in Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

The viewer seems to be looking at the barmaid in a way making her the object of his gaze.

But is there also a “female gaze” hidden in the “painting not painted”,

that is, in the reading of the Bar as seen from the perspective of the gentleman in the mirror? Is he seeing the barmaid as a subject?

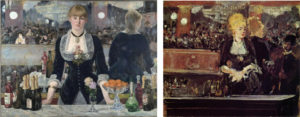

Manet’s painting and a mirrored version taking this perspective have been discussed already in Post 26 as shown in Figure 1.

Let’s take another look.

Figure 1: A Bar at the Folies-Bergére and the “painting not painted”

Much has been written about the “male gaze” in art, and a “New Art History” has criticised the expression of male dominance also in Manet’s paintings.

This includes the “12 Views” (Collins 1996) on A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), the main source for our discussion of the painting.

There can be no question that their criticism (not only feminist) of the “male gaze” – treating females as mere objects in art – is a valid social criticism. But already in Luncheon in the Grass (1863) and Olympia (1865), we have seen Manet as sympathetic to females who assert their independence through their gaze at the – presumably male – viewer.

To start, we should keep two things in mind.

First, the “painting not painted” is not an illusion which Manet depicts within the painting like a mirror image or a dream. Rather, the painting presents a puzzle which is designed to make the viewer use his or her imagination to re-arrange the “pieces” in ways that make sense.

Second, this kind of solution should be distinguished from re-interpreting his paintings in the light of theories (e.g. Freudism, Neo-Marxism, or Feminism) which cast a new light on Manet’s art but run the risks Champa is concerned about (see Post 25): We should not interpret Manet in ways that “make of what he doesn’t do the implied true meaning of what he does”.

A warning to be taken seriously, and, in a way, “the painting not painted” does exactly that. But the warning is not meant to blind us to the fact that Manet just loved irony, even parody, in his paintings. Playing with hidden meanings and with the expectations of the viewer is different from picturing mythological or historic “stories”, which he clearly abhorred, or applying theories which he did not know.

On male and female gazes

Approaching the painting, the viewer is captured by a seemingly realistic scene at a bar.

The mirrored couple, then, makes the viewer aware that much of the painting is, in fact, a reflection.

And this reflection is again questioned by the many details which contradict any realistic interpretation of the entire scene.

At some point (as described in previous Posts 25 and 26), the viewer will realize that he is somehow in the position of the mirrored gentleman. The “real” customer should stand in front of the barmaid just in the position of the viewer.

The “male gaze” may enter in two ways:

- The male viewer might recognize – as theme of the painting – the way a male customer is expected to look at the barmaid, seemingly confirmed by the mirror image of a customer staring down at the barmaid. He may even identify with this expectation and be prompted into a “male gaze”; he may imagine approaching the barmaid wondering whether she is a prostitute.

The viewer, thus, falls for the illusion which Manet produced by the realism of the painting.

He, then, may proceed to a criticism either of the “male gaze” depicted and/or of Manet for holding it himself, depending on the viewer’s own ideology outside the painting. - The male viewer may realize that Manet is playing a game with the viewer’s expectations, the “male gaze”, and will search for further clues within the painting for alternative views.

The surrealism of the mirror image will encourage him in this search.

What about a female viewer?

- Is she assumed by Manet to take “the role of the male” and interpret the painting – like the male viewer – in accordance with the dominant gender stereotypes at the time? Manet, the realist, just depicted purposefully a scene of potential prostitution, perhaps to express social criticism, and he assumed a male viewer – as reflected in the mirror – to support his realism?

- Is she going to realize that Manet is playing with male expectations, and is she going to search for clues which encourage taking “the role of the female” and allow for a “female gaze”?

With MyManet, we obviously chose the second option.

The basic question is, of course, to what extent we – viewer and critics – are willing to credit Manet with anticipating the “male gaze” and with incorporating into the painting not only a social criticism of this gaze but also the alternative of a “female gaze”.

Is there a “female story” to the “male story”?

If we follow the “male story”,

the male viewer will be irritated by the fact that the “real” barmaid is somewhat avoiding his gaze.

Looking into the mirror, he will see himself impersonated by the gentleman in the mirror. This man is luckier, it seems, since the mirrored barmaid is more sympathetic, leaning toward him, but she is looking less like a potential prostitute (see Post 26).

This puts the viewer in an ambivalent position: does he really want to exercise a “male gaze” treating the barmaid as an object of his desire, or does he want her to look back at him as a female subject – as shown in the “painting not painted”? After all, the avoiding gaze of the “real” barmaid may very well be “caused” by the viewer’s “male gaze”.

Looking again at the couple in the mirror, he may realize that there is something quite uncanny about those two: He is too close to her and too large hovering over her in an unrealistic, imposing position; she is not meeting his gaze in a sympathetic way of “seeing being seen” – like in the “painting not painted” and shown in Luncheon on the Grass.

The ”male gaze” of the viewer is thoroughly disclosed and compromised!

If we follow a “female story”,

the female viewer may, at first, understand the wary gaze of the barmaid being subjected to and avoiding a “male gaze”. The mirrored couple with the imposing male will confirm her view.

But then the puzzle will take over: Why is the woman so different? Why is the gentleman too close and too large? Is there a different female identity implied by the clearly different woman in the mirror?

Imagining this other woman, the female viewer will “see” someone like in the “painting not painted” – a subject looking back at her.

Realizing that she is now looking from the position of the gentleman in the mirror, she might imagine mirroring of the painting like in the “male story” and – without identifying with the male viewer in front of the painting – turning him into the mirror on the left.

Now, the female viewer is meeting the gaze of a barmaid “seeing being seen” by a sympathetic viewer which need not have (but may have) sexual connotations (the assumption of potential prostitution being distinctly male).

The “painting not painted” clearly underlines the subjectivity of the barmaid who rejects being made a mere object by the “male gaze”. Showing a self-assured female subjectivity and identity is something Manet has done before, in fact, in all of his major paintings of women discussed previously.

Further supporting this view is an important change we witness from the study to the Bar (Figure 2):

- The study shows a rather dominating barmaid looking down on a meagre customer.

The reflection in the mirror seems to correspond to the “reality”.

Manet’s intention to take a critical stand toward the “male gaze” is confirmed by this parody. - The final version shows the evasive look of a barmaid now more front and centre.

The effect of the “male gaze” appears to be his theme.

The self-confident barmaid has moved into the mirror.

Why this change? If not to initially capture the attention of the (male or female) viewer with a facial expression and posture requiring further explanation and involving the viewer in an intriguing puzzle.

Figure 2: Comparing the study with the final version of A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

The study unambiguously employs the “male gaze” and is easy to interpret by both male and female viewers, the final version is not. Divergent interpretations of generations of art historians attest to that. Rejecting the “male gaze”, the painting – not only the barmaid – asks for alternative readings which do not amount to a mere elaboration and confirmation of the “male story” based on the contemporary setting of the Folies-Bergère.

Especially the “female story” may raise doubts that female viewers will, indeed, imagine a complicated narrative along those lines (watch out for hidden sexism).

However, the “male story” is not really less complicated following pretty much accepted interpretations by (mostly male) art historians.

The descriptions are also more involved, while the reader may agree that looking at the images the female narrative is as accessible as the male version.

Evaluating the “female story”, it is enlightening to review the essays of the two feminist art historians among the “12 Views” : Carol Armstrong and Griselda Pollock.

Again, I will only extract some relevant aspects for our discussion:

Armstrong – optical ambiguities masking misogynistic gender ideology

Armstrong offers her own analysis of the “layers of illusionistic depth” (41) identifying the ambiguities and inconsistencies. The painting combines elements like a “collage” and the “optical ambiguities are really sexual ambiguities” masking a “misogynistic gender ideology” (42) resulting in the equation

spectator=male / object of vision=female.

For our purposes, the equation describes the “male gaze”, but, according to Armstrong, “this equation is nearly defeated”:

What we are offered to see in the painting is not “what we were waiting to see” (42).

Armstrong suggests three expectations not painted:

- a picture showing the consumption of the sexual promises presumably made by the mirrored barmaid to the customer but not realized in the painting

- a narrative showing the eventual meeting of human gazes, with the viewer and within the mirror, which is not happening

- seeing some version of ourselves;

instead, “we feel, rather uncannily, that we are not there … as subjects we are absent”,

and this applies to both female and male spectators, since, “the spectacle’s male and female cases, are sewn together to form a Janus figure” (42).

In view of our “female story”, three aspects are interesting:

- the first expectation, in a sense, assumes the painting under a “male gaze”

- the second expectation hints at the alternative, our “painting not painted”

- the painting is not analysed under a specifically female gaze – male and female views are “sewn together” – but rather under a general feministic perspective of the art historian criticising the “male gaze”.

Thus, Armstrong also suggests alternative “paintings not painted”. We learn something about a feministic view, but little about a specifically female experience of the painting different from a male one.

Griselda Pollock – The “View from Elsewhere”

Pollock claims an approach “to acknowledge and invite the sexual differentiation of spectatorship” (284) – to take the feminist “view from elsewhere”.

Writing her essay in form of an exchange of personal letters with a fictive “Feminist Scholar” and (obviously fictive) with Mary Cassatt, the friend and painter colleague of Manet, she wants us to join her in front of the painting and sharing her personal view:

“But like others before me, when I stand in front of the Bar I am now drawn into that play …” (290).

In view of MyManet and the “female story”, three aspects are relevant:

First,

Pollock subscribes totally to the characterization of Manet and his art as presented by the “big Others” (Pollock), namely, John Rewald, T.J. Clark and “to a lesser extent” Robert Herbert. Referencing the feminist art historian Novelene Ross, Manet’s painting is the art of a flaneur and dandy, a member of “the emergent bourgeoisie (that) produced a particularly vicious and confining concept of femininity” (284), with a “personal delight at being a man of his own time”, who especially in his last years “obsessively” rehearsed the “myth of La Parisienne” (305).

She backs this description up with Manet’s fascination with fashion, although his artist’s eye for modern beauty enhanced by fashion is not unequivocally linked to treating women as objects.

Pollock presents an informative example herself:

Manet’s arguably most fashionable picture of a beautiful woman is Spring: Jeanne (1881) shown in the Salon next to the Bar and eliciting exalted reactions by male critics. The “male gaze” clearly had a field day.

But then, Pollock’s friend Laura Mulvey pointed out to her that the face displays some curious similarity to the barmaid and that the descriptions of the critics did not correspond to the features of the portrait expressing “almost melancholy”, so that “the face stalemates the image of La Parisienne that the critic wants to see” (298).

If we agree with that observation, then we should be careful not to simply attribute the “vicious and confining concept of femininity” of the bourgeoisie to Manet.

If Manet aimed to “stalemate the image of La Parisienne”, should we interpret this only as the artist’s attempt to find “some telling, aesthetic form” (304)?

Or should we look for a different underlying concept of femininity in both of Manet’s paintings?

Second,

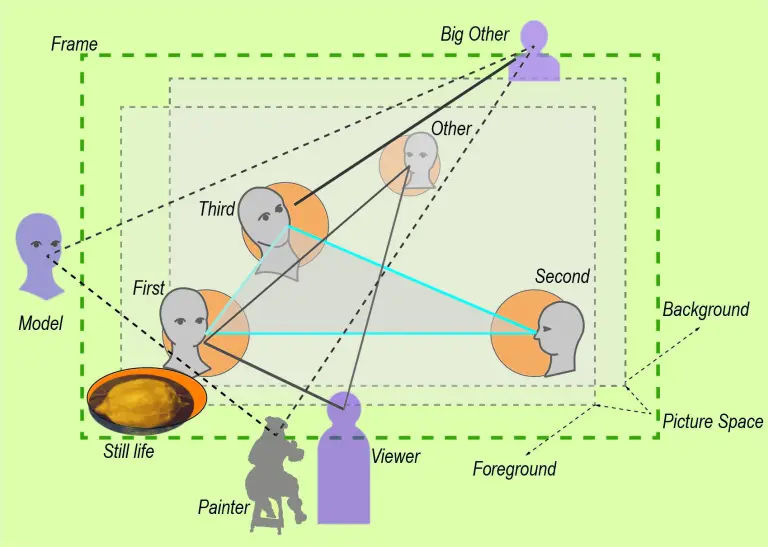

Pollock does detect clues for another view, the feminist “View from Elsewhere”.

Looking at the “reflections” of the painting, her gaze is drawn to the periphery to the “signifying female figures” on the balcony to the left. Two of the three women have been identified as prominent representatives of La Parisienne, but the third is generally recognized as citing Mary Cassatt’s painting At the Opera (1879) (see Figure 3). What is overlooked, according to Pollock addressing Cassatt, is “the radical ‘translation’ involved in taking your young bourgeois woman from the respectable opera and placing her among the demi-mondaines of the Folies-Bergère” (293).

The significance of this fact is not entirely clear. Are we to assume that Manet obscures with this move, and by placing her in the background, the feministic and critical potential of the figure? Or is the displacement meant by Manet to trigger exactly critical interpretations like Pollock’s? The former would explain why she later sees Manet only “obliquely and indirectly” (307) signifying the feminist dimension of the painting. The latter would be another sign for Manet’s inclusion of a “female gaze”.

Pollock does not tell, but what follows is a vibrant characterization of Cassatt’s woman At the Opera signifying a third – feminist – view from elsewhere. Pollock’s description of this view into “space off” fully agrees with the characterization of the Third in MyManet! The “authority” has only shifted to the “Elsewhere” of a feministic position. The woman is “seeing without seeing being seen” – as is Cassatt’s woman by the gentleman on the balcony in the background .

Then, Pollock is trying to link Cassatt’s gaze out of the picture space with the “guarded non-look” of the barmaid who “appears but does not see”(Pollock). The barmaid is interpreted as a “subtle” solution of “a modern woman looking at the viewer”, not as challenging as Degas’ woman at the race course (Figure 3), but with a “reminder of that other woman, of Mary Cassatt and her representation of looking as active feminine desire” (303).

Figure 3:

Mary Cassatt At the Opera (1879)

Edgar Degas Woman with Field Glasses (1865)

Again, in view of MyManet, there is an interesting parallel. The woman on the balcony is seen as a Third and linked to the main figure, a subtle clue to interpret the barmaid also in terms of a Third – like in Manet’s scheme. However, it is somewhat puzzling that not the main figures in the painting – Pollock hardly mentions the figures to right – but the little sideshow on the balcony should provide the initial key to her interpretation. (In MyManet, the little scene of three women is a reminder of Manet’s scheme (Post 25)).

It is even more puzzling that “a modern woman looking at the viewer” – as Manet shows in Olympia or The Waitress and dramatized in Degas’ drawing – should be signified by a woman not looking at the viewer, even by a woman avoiding direct eye contact.

But Pollock is not really interested in a systematic analysis of all gazes, already the gazes of the other two women are neglected. Unfortunately, they are representatives of demi-mondaines who belong to the other “male world” of the painting.

Third,

Pollock admits another way in which the barmaid – the painting’s “oddity at the center”- is “attracting her gaze but then directs it to those ardent feminine writers of the time” (304). There is “another history, one that enables me to make a feminist identification with its central female figure” (306).

In view of MyManet, this confirms the potential within the painting for a distinctly “female story”. Pollock does not use the mirror image of the couple to the right to explicate a feminist view, but choses the citation of Cassatt’s woman on the balcony to the left.

But she is “drawn into the play” as a female identifying with a female.

The problem is, she does not credit Manet with aiming at this effect. On her account, her female sensitivity detects the “oblique” and “implicit” signs of a “female story”. In her postmodern theory of the painting as a text, the author “Manet” is not the subject writing his story. He is seen as an individual reworking “heavily loaded ideological materials” which import into the painting both the “male gaze” of the ruling ideology and signs of the “female gaze” of an emerging feminist movement. The scene where it happens is the studio where Manet’s labour and the model Suzon’s labour meet “in a concrete social space” (307).

In view of MyManet, Pollock demonstrates that the painting enables female identification through a distinct “female story”, at least, if we attribute to him more authorship of the signs revealed by both her and Armstrong than Pollock is willing to do.

A basis for acknowledgment is provided by Pollock herself when she is referring to the concrete social space of the studio and the interaction of Manet and his model Suzon in the production of art – Manet’s “very signature as an artist” (307). So far, MyManet would agree.

Then, she imagines those “ardent feminine writers” (who evidently are not totally confined by the bourgeois concept of femininity) as campaigning with Suzon in the streets of Paris. But she does not consider that his working class models, Suzon as well as Victorine Meurent, or Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, his close friends, art colleagues, and modern women, had influence on Manet in that “concrete social space”. We should assume that their interacting creativity – of both sides, female and male – allowed for a (relative) independence resembling that of those pioneers of the feminist movement, not in the field of politics but in the field of art.

From all we know, Manet had a great social sensitivity, he respected women, and he was a contrarian not readily accepting social norms whether inside or outside the studio.

After all, his Olympia dared a very direct gaze at the viewer; she did not stare from a safe distance through field glasses at Edgar Degas betraying his ambivalent relation to women including his friendship with Mary Cassatt.

The surrealistic couple on the upper right side, the free-floating mirror image of the bar, and the strange depiction of the feet on a trapeze in the upper left corner are just three of the more obvious elements which breach a straightforward realistic interpretation.

They suggested another layer beneath the realistic illusions, the “painting not painted”, and motivated our search for a “female gaze”.

So, let us take another look at Manet’s realism!

See you in about two weeks!

Leave a Reply