Two essential features of composition in Manet’s scheme – in MyManet – are the figures’ gazes and the setting of the puppet theatre, or:

the relation between the social space of gazes and gestures and the material space of the setting on stage.

Manet made deliberate choices on both features when he created Luncheon on the Grass.

This we understand better looking at two studies for the Luncheon

and the X-ray visualizing Manet’s first draft underlying the final version.

In Figure 1, the four versions are compared, scaled to the same size, and supported by diagrams indicating perspectives:

Figure 1: Comparison of four versions of the Luncheon on the Grass

A – the final version of Luncheon on the Grass 1863

B – a later copy made by Manet himself dated between 1864-68

C – a study in watercolour with pen and ink dated between 1863-65

D – a print from an X-ray of the final version revealing a first draft

All four versions are presented and discussed by Juliet Wilson-Bareau (1986, p. 37ff)

– including a comparison with the painting Pastoral Concert by Titian and the etching by Raimondi after Raphael’s Judgment of Paris (see previous Post 8). Her X-ray analysis is a much acclaimed and quoted source in the discussion.

Wilson-Bareau proposes that the study (C) was made from the final version, and that the copy (B) was probably made even later. She concedes, however, that the sequence is only hypothetical since the exact dating is unresolved.

Her analysis demonstrates convincingly how Manet was experimenting with elements and their composition directly on the canvas and even at a late stage (like inserting and deleting a little dog to the left of the nude).

She concludes:

“One of Manet’s major problems with the Luncheon was evidently his difficulty in integrating the very solid, sculptural group into the original open and airy setting” (p. 39; title adapted as Luncheon).

In view of MyManet, I suggest a slightly different sequence and interpretation of his “problems”.

Two major changes are occurring between the draft in the X-ray (D) and the final version (A):

– On the left side,

in the X-ray an open view reaches from the foreground to the open landscape beyond the river,

with grass and bushes in the foreground instead of the clothing of the nude in the final version.

– In the group,

the gaze and position of the head of the man next to the nude is changed;

in the final version, he looks slightly upward into some undefined distance

rather than connecting with the other man as in the X-ray,

while his head – in relation to the nude’s face – is a little moved upward and forward in (A)

placing the three faces almost onto the same plane in the picture space.

Looking at the final version, the X-ray, and the study C, it is remarkable that all three versions show the same “solid, sculptural group”. This is indicated by the identical white triangles connecting the faces and by the position of the background female in the diagram of perspectives.

“Sculptural” may not be the appropriate term, since the triad is rather “flat” with the second woman set backward and too large in perspective. But I agree that the impression is rather “solid”; the formation of the four figures appears to be the same and clearly predetermined in all three versions, and rather independent from the landscape in the X-ray.

Taking up the first change:

Manet may have seen a “problem” with the integration into the landscape, but he resolves this “problem” in a rather unusual way by enhancing the difference between the landscape on left side and the solid group!

He introduces the “split horizon” from Pastoral Concert (the two perspectives in the diagram) and accentuates the vertical divide (left red line) by dark bushes and trees above the nude’s head.

Then, he keeps the “too large” woman pushing the background forward and the horizon upward and promotes the artificiality on the centre and right side – the “stage”.

He paints the background rather indistinct as “coulisse” and fits the triad into a middle ground with reduced depth. To maintain the balance under these conditions, he introduces in the foreground the elaborate “still life” to the left and a dominant dark tree to the right.

All this makes sense, when he is determined to preserve the formation of the group though violating a “natural” perspective. He is not caring about integrating the group “into the original open and airy setting” (see Wilson-Bareau above).

Manet invents a programmatic scheme.

Taking up the second change, the gaze of the man next to the nude:

This change raises the question of the role and dating of the study (C).

Wilson-Bareau suggests that the study is made after the fact, after completion of the final version. Her argument appears to be that the study reflects too closely the original to precede it.

Placed before the X-ray, the differences of the study with the X-ray become incomprehensible.

Placed between X-ray and final version, Wilson-Bareau apparently would expect more resemblance with the X-ray.

But why would Manet do that kind of study after the fact?

Certainly not to prepare the later version (B) which is in many ways different again, as I will show below.

An alternative interpretation is suggested in MyManet.

First, it is telling that the left side of the painting is not explicated in the study. This side includes in the final version the attractive “still life”. Why would this be neglected in the – admittedly, unfinished – study?

Second, it seems that Manet wanted to clarify the formation of the group before changing the left side:

The crucial change from the X-ray appears to be the face and head of the man next to the nude!

For the direction of this gaze Manet has no example in either Pastoral Concert or Judgement of Paris. He has to decide where the man should look, and he is not satisfied with an internal communicating gaze to the other male or with an “absorbed” gaze within the triad – as in the X-ray.

If Judgement of Paris is to be the model, then the gaze has to be directed toward the “authority” or Big Other – the god Jupiter arriving from the sky.

Thus seeing the study as an experiment for the gaze of the Third – in terms of MyManet – also underlines the importance that Manet attaches to this gaze!

To my knowledge, only Gisela Hopp (1968, p.23) has declared the gaze of the Third, in connection with the gaze of the nude, a decisive centre of gravity in the design of the painting, although she tries to derive this crucial role only in terms of internal design of areas, colours and perspectives.

(In her words: “Sein Blick ist erst der endgültige Kernpunkt des Bildes, nicht zu lösen von dem der Frau, aber auch für diesen Ausgangs- und Anziehungspunkt.”)

MyManet could not agree more!

It is interesting or puzzling that the nude’s gaze in the study (C) seems to follow the gaze of the man next to her – not gazing to the viewer! This is difficult to understand, if the study is made after the final version, as Wilson-Bareau proposes.

Rather, experimenting with her gaze in conjunction with experimenting with his gaze demonstrates what Manet is attempting: designing the interactive effects of the gazes in constituting a certain social and pictorial space.

When the nude is not looking at the viewer, the interaction with the viewer is lost and the gaze of the man is not effective anymore either, because it loses its singular force.

Finally, we have to consider the later copy (B).

Wilson-Bareau offers a questionable interpretation – from the view of MyManet.

She perceives in the copy “a more coherent, close-knit relationship between the foreground figures, while … improving the perspective view of the bather in the background” (p.39).

In my view, Manet appears to be testing after the fact and after receiving all kinds of harsh criticisms about his “failures”, whether his programmatic scheme is successful in achieving what he wants to achieve.

He revises all the major changes which account for the originality and modernity of Luncheon on the Grass:

- The perspective is “improved” by reducing the size of the background woman, setting her lower and lowering the horizon, and creating a more integrated background across the painting breaking the dark vertical above the nude.

- The man to the right is moved closer to the other two figures creating more intimacy (see right red line and perspective). He is also positioned a little bit lower and to the front (white triangle), while the other man appears a little smaller following the perspective toward the woman in the back.

Together, these changes produce a less “flat” middle ground extending into the depth of the painting. - The man next to the nude is now modestly looking toward the man to the right – sinking back into insignificance.

The result is a more “natural” setting which might have caused less of a scandal, because viewers could “read” those pastoral scenes – but we certainly would not be talking about this painting as a starting point for modern art!

The dynamics in the composition – the perceived lack of intelligibility, of inconsistencies and ambiguities – aroused the criticism of the art community, but caused also the later recognition of its ingenuity.

No wonder that Manet did not finish or exhibit this version!

Maybe he kept it ready at hand in his studio to show it to anybody worth to be engaged into a discussion about his innovative great scheme in the final version.

To be sure, this scheme is a hypothesis about the concepts guiding Manet. But I think it demonstrates two things:

- It is necessary to consider not only the sources inspiring Manet to understand his compositions, especially, since he is substantially changing and adapting them to the needs of the emerging painting.

- It is not enough to interpret Manet’s composition as “defined in terms of their rejection of academic conventions” (John House 1986, p. 12). The rejection is a critical attitude certainly shared by Manet, but it does not yet explain the programmatic choices and specific innovations introduced by Manet.

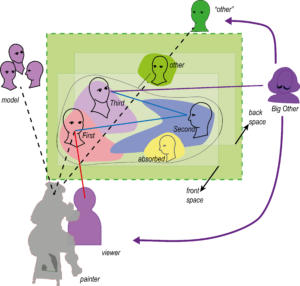

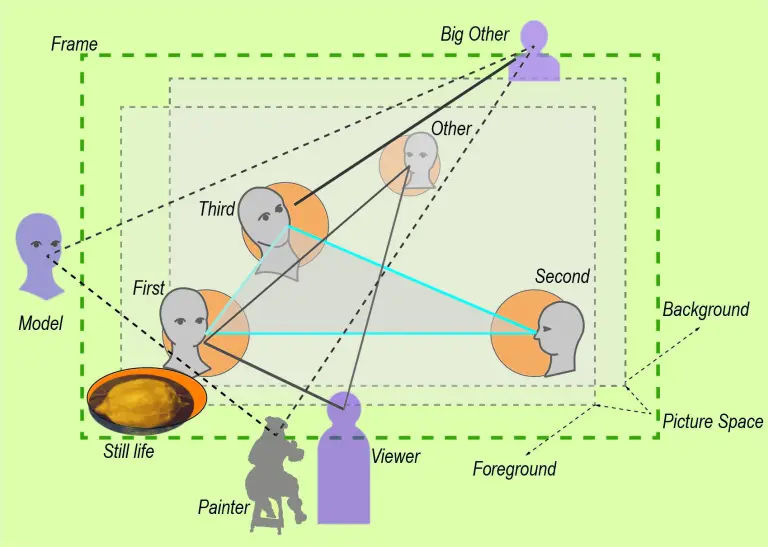

Time to summarize the elements of this scheme in form of a diagram integrating the results so far:

Figure 2: Manet’s Scheme – Composition in Social Space

The diagram should not be understood as a “manual” which Manet is following in the composition of Luncheon on the Grass, or in the creation of any of the other paintings to which we will apply the scheme. The diagram is mediating between the painting itself as experienced by us today and the process of painting as an event happening about 160 years ago. It is a tool for understanding – as are all diagrams – not a “theory” of the painting.

The essential dynamic is the interaction of social and pictorial space, of the roles outside the painting with the roles inside the painting.

Obviously, such a dynamic is – in the strict sense – only meaningful in figurative painting. And not all figurative paintings, and not all of Manet’s figurative paintings, are exemplifying this scheme as developed in Luncheon.

To understand our experience of other types of painting, we will have to introduce new concepts and schemes which appeal to different ways of relating to “What do pictures want?”(Mitchell 2005).

Manet is inspired by the structure of the puppet theatre which provides a model or stage for the activity of painting.

As anybody who has witnessed a puppet performance knows, there is no clearly defined inside and outside in the relation between audience and performance. The relationship is negotiated as the “show goes on” in each performance.

In terms of painting, we should imagine a situated installation artwork with the painting presenting certain elements “performing” on the “stage” carried by the canvas. The essential medium for this “performance” is the way our eyes move through the painting following the network of gazes and gestures of figures in the painting while engaging us and other agents outside the painting. In a sense, the relations are the “spiderweb” that stretches the social and spatial relations “in mid-air” reaching beyond the frame.

As indicated in Figure 2, Manet does not see these relations as realized on the flat surface of the canvas, although he is certainly aware of the material vehicle. He creates his own version of a socio-spatial “reality” which does not follow the rules of perspectives but stages figures and objects in a layered way, similar to a collage.

The “stage” is structured into a picture space rather narrow in depth and delimited by a front plane and a back plane. The front plane defines the foreground and is often accentuated by a “still life”, symbolized in the diagram by the lemon.

The picture space holds the triad of social roles with the First relating to the viewer and the painter, the Second integrating the relations on stage, and the Third linking to the “world beyond”, to society and tradition, symbolized as the Big Other or – in Manet’s case – by his idol of painting Diego Velazquez.

An interesting role in Manet’s scheme is taken by the “Other”. The “Other” reflects Manet’s insight that placing the scene “on stage” – like a puppet theatre performance – implies that there is an alternative perspective “from the back”. This “Other” may be represented within the picture, “painted on the coulisse” as in Luncheon, but the role may be only implied by the way the scene is staged.

As we will see in some interpretations of Manet, this “Other” – besides the relation between Third and Big Other – provides a welcome entrance for psychological or psychoanalytical interpretations looking from an unconscious “deep back stage” (often symbolized by a dark background) or for sociological interpretations emphasizing societal influences.

Similarly, the other external agents may be presented or unrepresented and only invoked by elements in the painting. Manet strongly reminds us of the presence of the painter by the very style of his painting. The viewer is, obviously, engaged by the outward gaze of the First; only on rare occasions does Manet introduce a “represented” viewer. The Big Other is implied by the diversion of the gaze of the Third, which avoids the gaze of the viewer and makes the viewer aware that looking at the painting is not only an individual subjective affair by the viewer – there is a “world beyond”. Finally, we have seen that Manet produces an awareness for the model – in case of Luncheon, by the amused gaze of Victorine Meurent who contacts the painter Manet in the process of painting.

The diagram offers a tool especially for the structural features of Manet’s scheme.

In that sense, it can be understood as representing aspects of the aesthetic form of the painting. However, the scheme is not simply aesthetic, it is incorporating a social form. It reflects how Manet (and, consequently, how the viewer) experiences the social reality and transforms it aesthetically in the painting.

This interaction between social form and aesthetic form, between the social reality of the painter and the development of new ways of seeing and expressing the reality in painting, has been brilliantly described, in the case of impressionism, by Robert Herbert (1988).

Obviously, the diagram does not tell us everything about Manet’s approach to painting.

There is much more to be told about the form and content of Luncheon on the Grass.

The diagram must be placed in a broader context to be meaningful.

Two important themes, we have already identified and postponed:

One theme is about the question how the paradigm of a puppet theatre can be aligned with Manet’s avoidance of “telling stories”. His figures are typically not engaged in clearly identified activities.

Another theme is closely related; it is about Manet’s realism which seems in conflict with the idea of a puppet theatre as well as with the application of an abstract compositional scheme.

Enough stuff for another post!

Meet you next week!

Leave a Reply