The model – or at least a source of inspiration – for the way Manet composes his paintings is the puppet theatre or marionette theatre.

That was the thesis presented last week. Today, we take a closer look at the implications of that view.

Most commentators of Manet’s work use at some point the image of a theatre to describe his way of “staging” the scene in the painting. But besides providing a metaphor for the direct relationship which Manet’s tries to establish between the viewer and the painting, the model of the stage is not further employed to characterize his compositional strategies.

MyManet proposes exactly that and – even more specifically – invites you to look at Manet’s paintings through the eyes of children watching a puppet theatre!

Let us consider some of the characteristics of a puppet theatre:

First, the space on stage of a puppet theatre is limited, especially to the front and back. The actors can move to the left and right, even up and down, creating the impression that the world continues beyond the stage on each side. But the actors are restricted in reaching out to the space frontstage where the audience is sitting and in retreating toward the back through the coulisse. The audience is well aware that the space backstage is occupied by the operator moving the puppets, even if they are immersed in the play. And Manet has made a suggestive little etching showing himself in disguise of a puppet peeking through the curtains from the back with some of his favourite requisites littered on the stage. (Note the balloon of My Manet flying by in the picture within the picture!)

Figure 1 Etching, 1861

Figure 2 Luncheon on the Grass, 1863

Looking at Luncheon in the Grass in that perspective, we sense that the three central figures are sitting on a kind of stage (in the studio), and we can almost see the background as a painted coulisse fencing off the backstage. The figures are somewhat crowded together. The man to the right is leaning out to the right, since he has no other direction to move.

Especially telling is the flat green background of the hand in the centre. In fact, this colour sets the tone for the entire painting (and for My Manet).

Manet is playing games with us, though.

He suggests a limited stage space, but he does not employ the obvious strategy to paint a frame, say, with curtains like Vermeer (see previous blog). The tree appears to be on the edge toward frontstage, and puppets could clearly leave the stage to the right. The situation remains “open” to the sides, not boxed in. Then, Manet moves the second woman “painted on the coulisse” forward, she is obviously too large, and, thus, is closing off the background. We cannot readily look past her into a background, she pushes forward and pushes the viewer backward.

But on the left side of the painting, Manet shows a realistic view into the far depth creating an inconsistency for our perception – we have to look back and forth – which further enhances the impression that all is just put on stage.

In support of this perception, Manet emphasizes the front of the stage – to the right by the tree, to the left by a wonderful still life, both not really connected to the central figures. Rather, they reach out frontstage to the viewer.

Violating perspective and the “proper” scale of objects – like the woman in the back – is a charming feature of puppet theatre as Manet’s friend Duranty pointed out – which may well have intrigued Manet (as noted by art historian Michael Fried 1998, p.474).

Thus, the pictorial space is full of “tricks”, but basically, we have a rather narrow space for the “action” and a frontstage and a backstage supporting, but also delimiting the pictorial space.

This feature, we will find again and again in Manet’s paintings, up to the “finale” in his famous “A Bar at the Folies-Bergére” twenty years later.

We return to that.

Now, I like to point out another feature of this “stage”.

We have three actors on this stage, or four, if we count the “virtual” person painted on the coulisse.

From a social point of view that is remarkable, since three is the minimal crew for any decent drama on stage.

One person can hold a captivating monologue, two can have a love affair, but the dynamics depend on the third person introducing alternatives and shifting alliances.

This is a formal aspect characterizing the potential for action.

Typical for Manet, there is no evident on-going action, the protagonists are somehow arrested in their postures for the moment.

They look quite vital and ready to resume whatever they have been doing. But for the moment they pause.

This impression has puzzled many interpreters of Manet, but – in my view – nobody has proposed a convincing interpretation.

Typically, art historians relate the fact that these persons do not communicate or interact in any meaningful way to the situation of modern life isolating or even alienating the individuals. A possible “modern” interpretation, but this does not contribute to any understanding of the composition in pictorial space.

We do have the feeling that something important is going on – the painting is obviously fascinating people for some 160 years – but what are they doing?

It is as if the actors are saying “Look, this is a play with three people. We are distinct persons playing specific roles”.

Unfortunately, we are not told the story line, only their positions. The way they look is obviously important for the whole composition, but their gazes do not create a closed space between them. Their common activity is interrupted, the space of their relationships is “opened”, and the attention of at least two of them is distracted.

The man to the right is kind of sustaining the relations within the picture space with his outstretched arm, but he is interrupting his communication.

On stage, it would be clear what is going on: the actors are attending to the audience and have to interrupt the “story”, they pause to establishing the contact with the people in the audience.

The philosopher of art, Richard Wollheim, proposed a somewhat similar interpretation:

Manet is introducing an “unrepresented” viewer entering the scene. The gaze of the woman establishes the presence of the viewer in a way that makes the viewer aware of himself or herself. This, in turn, motivates the real viewer to search for additional layers of meaning in the painting which this “unrepresented” viewer might see in the painting, but the viewer does not see yet exactly what the painter, Manet, intends to achieve.

Not all painters strive to achieve this specific type of active engagement of the viewer.

Following Wollheim, most of them don’t in most paintings. This also means that Wollheim is here introducing an element, the “unrepresented” viewer, which is not essential for “Painting as an Art” (his book title; 1987) in general.

Therefore, we might question his particular interpretation of Manet without taking a stand toward his general art theory (which would be beyond this blog). What is relevant in our context is that this “unrepresented” viewer is a formal element of composition which is quite independent from any content or “story” that might be going on in the painting.

To some extent, we encounter the viewer we already met looking at Vermeer’s painting, although now not in the corset of a perspective system. But not quite.

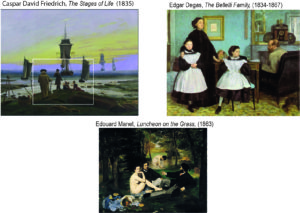

Wollheim compares Manet, on the one hand, with Caspar David Friedrich, a German “romantic” painter (1774-1840), and on the other hand, with the early Edgar Degas, his friend and painter (1834-1917). (Degas is famous for his paintings of ballet dancers, but he started his own “revolution” a few years later.)

In Figure 3, we see an example from both artists, although I chose different paintings to enhance the correspondences with Luncheon – and marked a “zoomed” detail in Friedrich.

Figure 3:

Comparing: Caspar David Friedrich – Edouard Manet – Edgar Degas

Looking at the Degas, I agree with Wollheim that the figures in Degas are just lined up to be portrayed.

The girl to the left establishes a contact with the viewer, but the essential content of the painting is not influenced. The relations in this bourgeois family are obviously problematic (look at the mother!), and this is what Degas wanted to present to the viewer.

In Manet’s painting, the figures have much more presence for the viewer, even though not all are looking outward. This involvement we “see” also in Friedrich’s painting. In fact, the entire painting is impressing itself onto the viewer. In this particular case, the viewer even sees him/herself represented within the picture space, because we tend to identify with the figure in the foreground approaching the group in the middle ground.

Friedrich succeeds here in presenting the experience of a represented viewer to the viewer. In other cases, he is attributing the experience of the scene to an “unrepresented” viewer whose intense experience gives the scene its “romantic” flavour, in Wollheim’s interpretation just like in Manet.

In my view, there is a crucial difference.

In Wollheim’s view, the “unrepresented” viewer is, in a way, outside the painting and might be approaching the picture plane until he is actually seen within the painting. This viewer is an integrated element of the perception of the scene, as if looking from within even if not represented inside. Wollheim is not employing some “deep” psychological or psychoanalytical processes (e.g. no Sigmund Freud; we have to return to this kind of interpretation of Manet’s paintings by other authors). Rather, it is our everyday imaginative capacity at work, similar to our dreams “mobilizing our memories of what nightly goes on in our heads” (p.164). No real mystery here, although – like with dreams – the world may appear sometimes mysterious and the space uncanny – like a castle ruin in the moonlight in a painting by Friedrich.

Wollheim assumes for Manet a similar naturalistic or scientific attitude towards our perception and the perception of the – represented or unrepresented – viewer.

But there is a difference.

As noted by Wollheim, the figures in Manet’s painting are disturbed from outside the picture; the distance to the viewer is preserved and with it the autonomy on both sides. Their gazes contribute somehow to the meaning of the painting without invoking some “story” and engaging the experience of the viewer in it! Note that Friedrich’s painting is loaded with symbolism. It is called “The Stages of Life” with people of all generations in a somewhat mystic landscape.

Originally, Manet’s painting had the generic title The Bath with hardly any “story” indicated – just a scene one might encounter around Paris at the time (which contemporary viewers found quite puzzling).

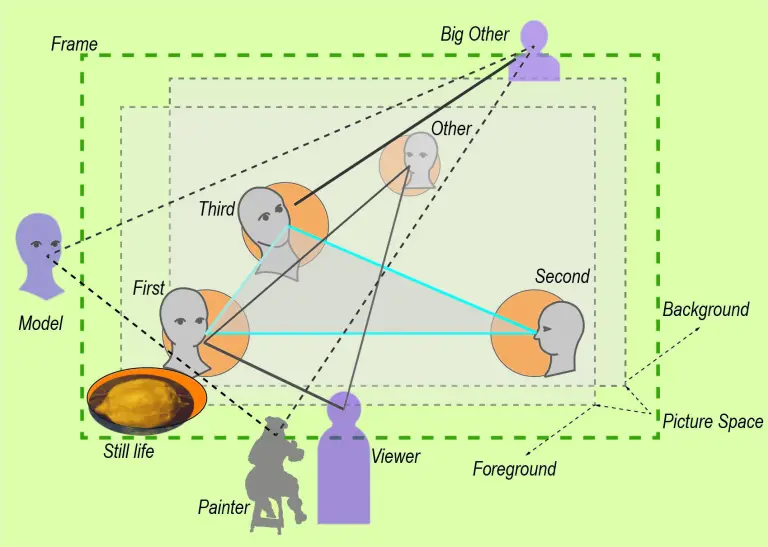

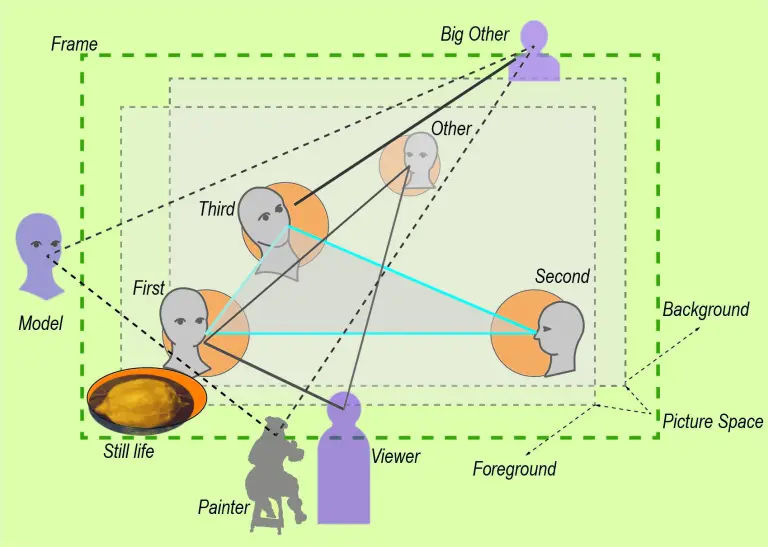

To understand, why I consider this difference important, we go back to the distinction of the space inside the painting and the space outside the painting.

For Manet, there are more persons outside the painting than an “unrepresented” viewer. There is the painter himself, the model, a friend, perhaps a novelist and art critic like Edmond Duranty or Charles Baudelaire (who visited almost daily), and they are all – virtually – sitting in front of the stage in the audience.

And unlike in a normal theatre, with actors on stage and a director and stage crew supporting them, Manet – like the operator in a marionette theatre – had to address each one of them through the figures in the painting.

No wonder the figures look in different directions, they have different roles to play in the communication with the audience outside the painting!

Figure 4

Social positions inside and outside the painting

The viewer is not fixed by perspectives in a certain position or in the privileged position of an “unrepresented” viewer. We are not invited into the perceptual space of the painter/viewer, but rather into a social event.

The viewer is quite autonomous, changing positions, even walking around as a critical observer and checking what is going on “backstage”. (Certainly, children try to go around to see what is back there!) The viewer can, virtually or metaphorically, look from the “back” as indicated in Figure 4. The position can be imagined like the second woman within the painting looking at the group from behind. Or like Manet, peeking through the coulisse – see above. The viewer may even take the position of the model.

Interestingly, Manet painted just this situation a year earlier (1862) portraying Lola de Valence, a Spanish actress and dancer. Manet was kind of “interviewing his model backstage”. On the left side, we see the audience looking at the stage and towards you, the viewer – and past two layers of coulisse – the pictorial space. This position or perspective is the view of the “other” in social space (or the “alter ego” of the painter in psychoanalytical terms).

Figure 5: Edouard Manet, Lola de Valencia (1862)

Besides, the painting is an example of the great interest of Manet in theatre, opera and circus, not only the puppet theatre, documented in paintings over his entire career.

We will return to the position of the “other” in the next post. In a later post, we also have to pick up the way Manet is avoiding any great “story” – unlike Caspar David Friedrich above or his “romantic” precursors and teachers Delacroix and Thomas Couture. He literally starts a “postdramatic” painting which makes us jump right into 20th century discussions on art and theatre!

For now, I like to emphasize two things:

On the one hand, the puppet theatre provides us – and, I argue, also Manet – with a model for real and virtual spaces inside and outside the painting or the pictorial space. These spaces form an installation inviting us to enter and walk around – much like installations in modern art over a hundred years later!

On the other hand, we realize that the spaces are constituted essentially by gazes and gestures of persons inside and outside the painting and between those inside and those outside. These spaces are social spaces and, therefore, we will take a closer look at how Manet paints the communication between the persons involved in the painting process.

Again, the model of the puppet theatre will prove to be helpful!

See you next week!

Leave a Reply