Contemplating in 1863 about Luncheon on the Grass, Manet might have asked himself:

How can I paint the activity of painting in a modern way?

This is the first question I posed in the “Installation My Manet” introducing the ideas behind my collage shown at the exhibition of the Järvenpää Art Society. (You will find the collage here. )

The collage was originally planned as a more elaborate installation occupying a whole corner of the room and inviting the viewer to step into a puppet theatre or marionette theatre. The figures of Luncheon in the Grass would hang from the ceiling onto a stage framed by curtains and backed by a coulisse with the second woman and the landscape. The painter (Manet in the costume of Vermeer) was to sit in front on a bench with the viewer as another spectator next to him. The “real viewer” approaching the installation would be invited to sit next to them (or at least, stand close to them). The puppet theatre would look somewhat like in the etchings of Alfred Legros at the time – a painter and friend of Manet – who looks himself invitingly at the viewer of the etching.

In the installation, the model would be peeking from the left side of the stage; Velazquez would drift somewhere on the upper right side flying in a balloon with Jupiter painted on it, hanging from the ceiling …

Some background material on the wall would explain what this was about. Additionally, I wanted to discuss the ideas with visitors.

That was the plan.

Then, Corona hit – and the installation was not possible anymore, let alone the discussion.

The gallery was closed.

Then, the Art Society came up with another idea to cope with the pandemic.

Each artist had the opportunity to create a piece of art over the span of one day and the activity was recorded and published on the society’s website. So, our painting of a painting would be documented on video.

Taking part in this event changed My Manet drastically. Now, I had only a day to produce a collage. (Actually, I took more time preparing the installation at home.)

The burden shifted to a presentation of the basic ideas as a text on the wall, and the discussion had to move into virtual space connecting My Manet with Your Manet.

As it turned out, this made me even more aware of what I wanted to do – and what not. Showing the activity of painting in a painting (or video) was – in my view – Manet’s aim.

But he did not want to be in the picture – let alone in a video, I am sure.

More precisely, Manet would have loved the new media and, perhaps, created multi-media installations. But he wanted to let the painting speak for itself about the realities of painting in modern life. Manet never talked or wrote much about his art – he painted!

What was – in my view – Manet’s approach to the problem of presenting the activity of painting without the painter?

I will address this question in two posts.

Still learning how to run a blog, I realized that I have to cut my contributions into digestible chunks.

Here is the first part:

Let us look at an alternative, Johannes Vermeer’s The Art of Painting (1665) (Figure 3).

Note that the painting is about 200 years before Manet, but he admired the Dutch Old Masters.

A problem with Vermeer’s approach is that we hardly see what he is doing.

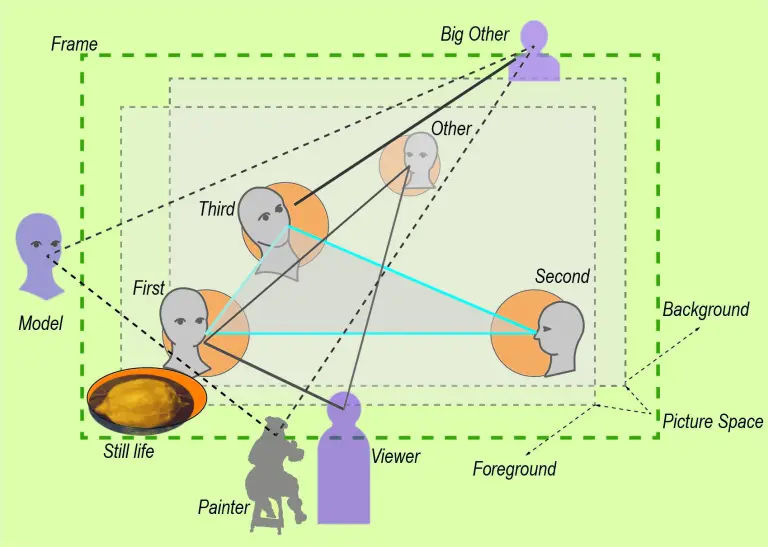

The painting seems to be unfinished, so we can assume that Vermeer wants to show the process as on-going. But the painter covers up the process. Moreover, Vermeer places the viewer in the space behind the painter, even makes room for the viewer to stand this side of the curtain conveniently drawn aside. Now the “real viewer” in front of the painting is induced imagining the “real painter” behind this imagined viewer as in Figure 4.

Now, this game of “who’s viewing whom or what?” is a lot of fun for art philosophers (we will return to it later), but not so much for Manet, who wants to paint. The “action” is taking place between him, the canvas and the model, not some 1-2 meters behind his back.

One issue is about showing the on-going process on the canvas.

One solution for this issue is for Manet to keep the painting “unfinished”, at least in part. The viewer (sitting next to him, see above) can finish these parts with his or her imagination while looking. The viewer might not even be aware of this active role.

Manet offers a painting “open” for interpretation, not a “final” product. Such strategies, keeping the viewer active, we will encounter again and again. But now, I want to look at the way Manet treats this space occupied by the painting, the painter, the model, and the viewer.

Actually, there are two spaces: one inside the painting and one outside or around the painting.

Both spaces are treated by Manet in a new and innovative way, which – in my view – is not adequately attributed to him in the literature. He is recognized as “revolutionary” in many ways, but there are still secrets to discover. His strategies are not new anymore, we learned from him, but he is not given due credit.

At least partly, this is a consequence of treating Manet as a precursor of impressionism. But Manet never was or wanted to be an impressionist, in fact, he never exhibited together with his impressionist friends, although they urged him to. Impressionists – roughly speaking – focused on the play of light on the surface of objects or landscapes.

Manet never abandoned the materiality and 3-dimensionality of his subjects or his space.

First, let’s look at the space inside the painting.

Most interpretations of Manet emphasize at some point that he is “flattening” the picture space and even his subjects; typically, this is seen as one of his “revolutions” which initiated modern art as we know it. Modern painting, so the story goes, accepts and starts with the fact that there is a 2-dimensional, blank, white canvas waiting for the marks of the painter. In my view and experience – this white surface is, actually, a horror stifling any creativity – especially, in its modern perfect fabrication. One sits in front of it and any search for “handles” to hang on your imaginary ideas are absent, and the hanging of them is frustrated. To make any mark on the surface, to splash any colour on it to get the inspiration running is better than this flat white.

The artists living in caves thousands of years ago had it easier, in a sense, the rocky wall suggested all kinds of marks. As soon as there is anything on the surface, we tend to see a “space”. The mark “stands out”, the colour creates “depth”. Then, we start to paint in this space and change it – even when we want to experiment with making it “disappear” or appear “flat”.

I think, Manet never worried about “flattening” things to a surface (of the objects and/or the canvas).

He wanted to escape the confines of the conventional approach asking you to create a “window” through which one would look onto real or imagined worlds structured by more or less perfect perspectives.

From Manet’s realistic point of view, it is even questionable to stick to a system of perspective, since we don’t see in “real life” the world in strict perspective.

This can be observed in Vermeer’s painting. He applied a perfect perspective – and the painting appears somewhat artificial and constructed exactly because of that. If violating the perspective meant creating “flatness” in the painting – so what?

Steps toward “flatness” look especially desirable from hindsight – from the point of view of abstract art.

Manet was trying something else.

He wanted to put the painting “on stage”, to create a pictorial space similar to a puppet theatre or marionette theatre. The model for this approach was readily available. His friend Edmond Duranty, a young novelist and critic, revitalized the tradition of marionette theatre at the time creating a public theatre in the Tuileries garden. Manet and his painter friend Alfred Legros, who depicted the theatre as shown above, were actively engaged in this venture. The art historian Michael Fried (1998) has described this engagement as a source of motifs in Manet’s paintings. But Fried does not exploit this model for the understanding of Manet’s pictorial space.

In the next post, we will take a closer look at the influence of the puppet theatre on Manet’s organization of the pictorial space inside the painting and the implied view of the setting outside of it.

Meet you next week!

ROGER BYRING

Very nice and thorough analysis.

My question concerns the pirtrait the Finnish painter Rafael Wardi did of our then president Tarja Halonen. He painted her with ambiguous “unfinished” eyes.

Tens of thousands of people went to Ateneum to see the portrait. The eyes of all these people and of people looking at fotographs of the portrait are directed at this ambigous face, and maybe ponder what others think of it.

Then, this is not a naturalistic painting.