Manet’s scheme – the MyManet scheme – did not emerge in one creative step, but over several paintings experimenting with figures, their gazes, and their roles.

As we have seen, the scheme implies at least three figures and their gazes within the painting. Therefore, we look especially at his multi-figure paintings, and try to find elements of the emerging scheme:

Question 5: How can Velazquez – figures within – and Courbet – figures outside – be combined in a social scheme?

According to Michael Fried, the years 1862-63 saw the breakthrough of Manet’s art (1996, p.1).

After copying The Little Cavaliers (1859) and before he created The Luncheon on the Grass (1863) and Olympia (1863), Manet painted four scenes with three or more figures (excluding graphical works and sketches):

Music in the Tuileries (1862), Spanish Ballet (1862), The Old Musician (1862), and The Fishing (1863).

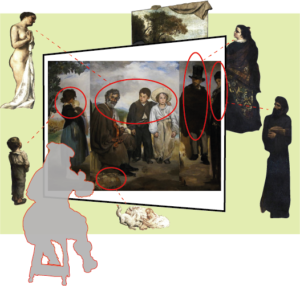

In Figure 1, the four paintings are shown together.

Figure 1: Four multi-figure paintings preceding the Luncheon on the Grass

Music in the Tuileries

Spanish Ballet

The Fishing

The Old Musician

What I find striking is that these painting are so different!

Would anybody (without some acquaintance with Manet) guess that they are even from the same artist?

As Fried demonstrates in detail, this is at least in part due to Manet’s attempt to integrate very different sources from past Old Masters.

In Spanish Ballet and The Old Musician, the reference to Valezquez and Spanish art is obvious.

In The Fishing, we find references to the French tradition (e.g. Watteau) but also to Rubens.

Music in the Tuileries seems to pick up The Little Cavaliers, and – assuming (wrongly) that the original was from Velazquez and that the Master pictured himself at the far left – Manet is putting himself in his place.

But citations go also across these lines e.g. with French masters also appearing in The Old Musician and Spanish influences in Music in the Tuileries.

Actually, Manet kept generations of art historians busy to find the references to past and present art and to identify persons in the painting.

While I find these discussions of sources and influences of different painting traditions very interesting in themselves, these interpretations emphasize the differences between the four paintings. Typically, Manet is described as experimenting with different styles and techniques, and often he is said to be still lacking certain skills.

What is somewhat missing – as far as I dived into the literature – are the common themes or issues guiding Manet’s exploration in these paintings. The theme of combining past and present in each painting is always acknowledged but the common themes cutting across these paintings are reduced to the development of different aspects of his painting style.

Music in the Tuileries receives in this perspective most recognition, since the painting appears to be most “modern” both in subject and in painting technique. The other three examples owe more to the past, it seems.

In Post 3, I pointed out one theme that unites Music in the Tuileries and The Fishing with Luncheon on the Grass, namely, the issue of scale. The paintings are different from Luncheon in their scale of the figures and the social and spatial relations between them, but they have in common an exploration of the effects of scale:

The Old Musician is, in this respect, comparable to the Luncheon: it shows the figures on the level of direct face-to-face interaction.

Music in the Tuileries and Spanish Ballet are like The Little Cavaliers in showing the figures lined up in a middle distance trying to keep contact with each other at least by proximity.

In The Fishing, this contact is broken or rather restricted to relations of body orientation and gestures. The grouping dissolves into a pattern of distributed small groups or individuals.

Manet does not like to paint large groups – like the traditional paintings of historical mass scenes of war or festivities. To connect larger groups in a composition, the painting needs a “story” uniting the figures – Manet avoids telling stories. The number of people produces problems, when you want each individual to play a specific role. It becomes even more of a problem when each person in the painting is assumed to have his or her own “story”. This is especially the case in a group portrait, where we expect that each individual has a distinct personality and a contact to the viewer – as in the typical portrait.

We can see the problem in the Spanish Ballet.

Manet invited the group into the studio to make a group portrait, and we can imagine how he found everybody looking at him. This was not the social situation, he wanted – we can feel the distance he created between the group and himself. As a result, he focused on two couples, dispersed the group, placed some dancers in a darker background, and tried to achieve unity in the composition by spatial rather than social relations – and he never tried to paint a situation like this again!

I do not think that Manet was incompetent to paint large groups or group portraits. He was familiar e.g. with the Dutch tradition of group portraits, and he found innovative solutions whenever he wanted them. But his interest in the direct relationship between the viewer and the action “on stage” is impossible or missing in those situations.

So, Spanish Ballet demonstrated for Manet that his concept of pictorial space – the puppet theatre – is not in alignment with a viewer facing a crowd or a larger group facing the viewer.

This, indirectly, supports the view of MyManet. (It also tends to contradict Fried’s concept of “facingness” of the whole picture as a central aspect of Manet’s art.)

At first glance, Music in the Tuileries is a counter example to the point just made – that Manet does not like crowds. But a closer look shows that Manet emphasizes a series of distinct figures, small groups, and even specific faces lined up from left to right. We see a series of individuals, and many of them have been identified as members of his social circle. The art historian Niels Sandblad (1954) is right, I think, when he draws a close connection with The Little Cavaliers. Most figures in the crowd are not more than an atmospheric background – except a few figures (highlighted by red circles in Figure 1) stand out.

Interestingly, the painting is structured by the trees into three sections.

Only in the left section, perhaps 4-5 figures look towards the viewer, most prominently one of the ladies (First).

She catches our attention and induces us to “read” the painting from left to right – just like in The Little Cavaliers.

The centre breaks this move – by a deceptive perspective deep into the park – but it is puzzling with its diffuseness of figures except for the strangely enhanced gentleman (Second) looking down at a sitting woman and for the “absorbed” children playing at the front edge of the painting (or “stage”).

To the right, again one gentleman (Third) stands out greeting somebody outside the painting lifting his top hat – taken directly from The Little Cavaliers.

Finally, a strangely enlarged gentleman (a reversed “other”) with a grey top hat is looking toward the back.

I have emphasized the references to the diagrams to highlight the “testing” of roles occurring in the painting.

As Sandblad sees it, Manet is distributing a series of “faces” that are “flat, unmodulated areas on the surface” replacing “reality with a kind of sign-language” (p. 63), an element showing an unusual “respect for the pictorial surface … most remarkable in the whole painting” (p.23). Sandblad detects here first traces of symbolism modifying Manet’s realism (distinct from current naturalism or emerging impressionism).

I would agree with him that Manet is presenting here a hidden constructed scheme arranging symbols of faces and gazes. And that this is not to deny that the painting is also the first “modern” painting of leisure activities of the urban bourgeoisie, as many art historians point out (like Herbert 1988).

But Music in the Tuileries can also be seen as testing elements of the scheme. However, the model built on The Little Cavaliers turns out to be an alternative second scheme for the middle range of the scale. We will encounter it again in other paintings (like Masked Ball at the Opera 1873).

Considering The Fishing in this perspective, it shows dispersed groups and individuals with a combination of social relations across spatial distances in a rather free composition. This arrangement should also be regarded as an alternative third scheme for the large distant range of the scale (like View of the World Fair 1867).

As I suggested in a previous post (P3), Manet has, obviously, not only one scheme for his compositions.

But MyManet tries to demonstrate the impact of a specific scheme – realized in Luncheon on the Grass – on other paintings beyond this special case. We will see this influence even in paintings following alternative compositional schemes.

So, let us take a closer look at the remaining fourth picture: The Old Musician.

As Fried tells us, this painting is a perfect starting point for analysing the way Manet is citing and borrowing from other paintings – an El Dorado for art historians. It is also a great example for the way Manet is combining freely – like in a collage – elements for his own purposes. He is not copying.

I have engaged in some own collage making. In Figure 2, I combined The Old Musician with the figures from Courbet’s painting representing the roles outside the painting. Although not exactly, since I mirrored the inner group of three figures, and added some red ellipses and a face diagram to enhance the critical elements.

Figure 2: Combining The Old Musician with Courbet’s roles outside the painting

The diagram fits to the emerging scheme almost perfectly. We see all five roles outside the painting and their corresponding “partners” within:

The triad – First, Second, and Third in the middle (with Second and Third switching positions).

The girl – inspired by the boy? – looking from the left like another “represented” viewer.

The “other” – looking from the back; quite tellingly, he is The Absynth Drinker from Manet’s own painting (1959), thus, Manet is citing himself as the “other”.

The “authority”– the philosopher or the representative of society and tradition is cut off by the right frame.

And we find a little still life marking the front stage.

The “absorbed” figure is eliminated in this case; we have kind of an “absorbed half-figure” represented by the cut-off philosopher.

The experts agree that

“simplification”, “sincerity”, and a “new type of connection with the beholder”,

besides a “resistance to available modes of pictorial understanding” (Fried p.21-23), is characteristic for Manet.

So, Manet, looking at the painting as his own first viewer and critic, might have reached some conclusions:

For simplicity, the girl as a “represented” viewer is not really needed in a generic scheme realizing a new type of connection with the beholder. A painting surely should allow for additional figures, but they may vary with the subject.

In communicating the relationship with the “authority”, the Third has to be credible as connecting to an agent outside the picture space and not e.g. day dreaming. A boy, not even looking at the “philosopher”, may be not convincing and evoking other interpretations e.g. related to his youth or social class.

Placing the “authority” clearly outside the painting (like Velazquez) may be the better solution for the generic scheme. Although, depending on the subject, strong clues for the implication of “authority” may be required (like Velazquez representing the royal couple in the mirror of Las Meninas).

Citing the painter himself as the “other” is a nice ironic touch, but for a generic scheme it will not always work .

The “other” looking from the back should perhaps be less dominant.

Moreover, like in the lithograph with Polichinelle peeking out from the coulisse (Post 2), it might be better to imply the “other” rather than representing the figure in the painting e.g. by moving the background forward and making room for imagining a social space “behind the stage”.

So, in the perspective of a sincere, new scheme presenting the “painting of painting” – including roles inside and outside the painting – we should focus on the essential elements.

Now, Manet needs a subject that allows for the realization of the consolidated scheme, but also for his way of mediating between the past and the present while critically and ironically distancing himself from both.

The nude is clearly the “classical” subject which – transposed into the context of modern life – offers all the possibilities for confronting existing traditions in art and society.

The paradigm of the puppet theatre provides not only a vision for the composition, it clearly feeds into all ironic and critical intentions of the project.

So, the subject will be a Luncheon on the Grass with a female nude accompanied by the three additional figures required by the scheme!

See you next week!