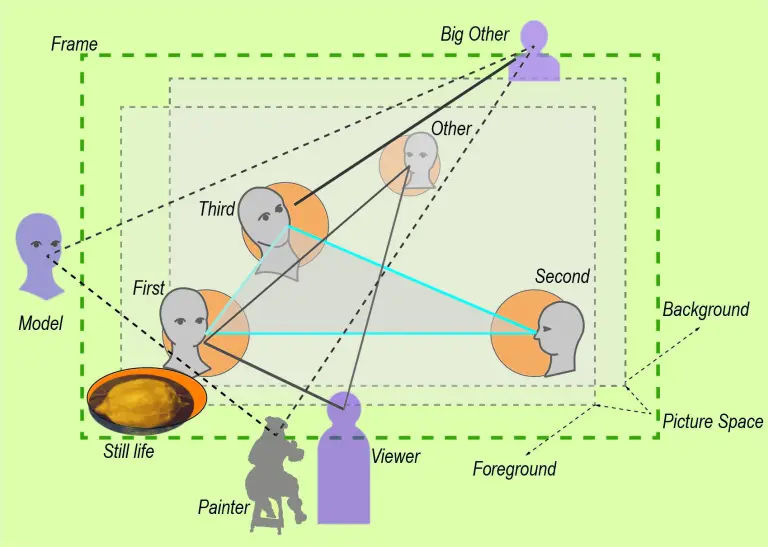

Manet’s last masterpiece – A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) – is valued by many as “one of the canonical images of modern art history” (Armstrong). Over a hundred years later in “12 Views on Manet’s Bar” (Collins 1996), art historians from a broad range of approaches (Marxist, psycho-analytic, structuralist, post-structuralist, feminist, and “standard practitioners”) were invited to discuss their different views choosing an especially suited example for such a comparison – Manet’s masterpiece.

Figure 1: Edouard Manet A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882)

The literature on this painting is endless and still growing. Therefore, I will limit my references in this post to essays in this collection, with one exception as explained below. The collection has become a standard source itself and it is so rich of insights into Manet’s work that I will not try to discuss the contributions fairly and not all of them – I will just ruthlessly explore and exploit them for MyManet.

My question is: What do we see in the Bar if we look at it with the eyes of MyManet?

My view is especially unfair, since it will largely exclude a major focus of the “12 Views”, namely, the demonstration of the way that different theoretical and ideological backgrounds can make substantial contributions to art history.

Central positions of a “New Art History” are: a Marxist social history exemplified by an influential book on Manet by T.J. Clark (The Painting of Modern Life 1984) and critically reassessed (Driskel, Gronberg, Herbert, House); psycho-analytic theory based on Freud and Lacan (Carrier, Collins, Levine); and feminist analyses (Armstrong, Pollock); they are confronted with positions of more “standard practitioners” (Collins) in art history (Shiff, Boime, Champa, Flam) .

MyManet can profit from all positions in some respects – and will disagree with each of them in others. Which is not really surprising, since this applies to all the other contributions, too.

In the following, I want to take a closer look at two issues:

- the context of the painting in the discussion

- Manet’s realism and the role of the mirror

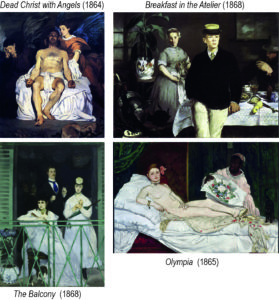

Based on these reflections, I will suggest an alternative view inspired by Manet’s scheme.

The scheme will not apply in a straightforward way,

but provide a new twist to the other “12 Views”.

This alternative I will presented in the following post.

The context

Most essays follow the invitation of the editor and limit their contribution to this particular painting, its socio-historical context, Manet’s work and life in Paris at the time, and selected other paintings relevant for the specific perspective they want to add to the discussion.

A special issue is the role of the mirror addressed by all authors and taken up below.

Another issue evolves around the question who the barmaid – the model Suzon – is or is representing:

- Is she a typical lower class working woman determined by her class situation?

- Is she a casual prostitute not only offering drinks but also her body?

- Is she symbolizing, in her somewhat constraint frontal posture, religious representations of Virgin Mary?

- Or is she presenting the duality of female identity at the time between the “virtuous” (bourgeois) woman and the “fallen” whore?

- In what way does Manet’s biography as an upper-middle class male or his problematic family background (Is his son actually the son of his father?) influence the content of the painting?

- What role is his disease and nearing death playing?

These analyses – largely responding to the influential work by the art historian T.J. Clark – deliberate on legitimate and interesting questions.

But, they tend to neglect two aspects which are important in view of MyManet:

First, socio-historical considerations of class situation and gender issues of the time describe important conditions of Manet, his work and his models. Consequently, “the barmaid’s unexplained refusal or inability to respond positively to the male spectator’s intense gaze” is readily interpreted as reflecting class domination, female suppression, or Manet’s “pessimistic convictions on relations between the sexes” (Collins p. 129).

But this perspective tends to underrepresent the emerging individual self in modernizing society and the new liberties gained or taken not only in bohemian subcultures.

For instance, Boime (60) sees the barmaid more in context of the Parisian life enjoyed by the “flaneur” Manet. The barmaid becomes a “female equivalent of the flaneur” and her moment of private withdrawal from the scene – as expressed in her absent gaze – becomes an expression of a “residue of subjectivity” distancing herself from her public performance as barmaid.

Thus, there is a gap between the societal conditions and the individual situation, and we should be careful in drawing conclusions about the effects of the former on the reactions of the latter – and about Manet’s intentions to depict social criticism in his final work.

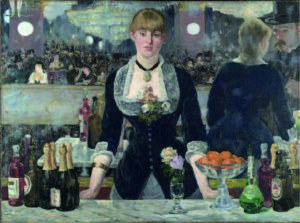

Figure 2: Paintings by Edouard Manet related to the Bar

Second, there are not only other contexts for the interpretation of the role of the barmaid as characterizing Parisian life; there are also questions about her depicted role as describing more generally the role of women in Manet’s art.

Pollock (306) points out that the painting does not just show Parisian life at the time but keeps the viewer aware of the studio situation and, thus, of Manet’s relation to his models – typically friends and family – and not only to the particular subject, like the barmaid Suzon modelling herself.

The expression of the face should be seen in context of the whole painting, and interpretations placed in the context of his actual relations to females. As Pollock observes, the painting could not have been painted by a “bourgeois woman” (290); thus, a male bias is clearly present in the painting. But such a bourgeois woman is featuring in The Balcony (see Figure 2) “just looking” at the viewer, while Manet’s whole attention (and admiration) seems to be focused on the other woman (Berthe Morisot) “looking to the ‘space off’ signif[ying] the inscription of female desire for ‘the more’ for which feminism stands” (294; emphasis added). Pollock makes no reference to The Balcony, but she suggests that the woman with the opera glass on the balcony in the background of the Bar is a reference to a painting by Mary Cassat – another independent woman, painter, and friend of Manet. Pollock (among other feminist art historians) describes Manet as very sympathetic to the cause of female vote in politics and their independence in art.

In this perspective, it is telling that most authors dwell on the issue of prostitution or on the symbolic dualism: the barmaid’s posture is resembling religious depictions of Virgin Mary while her mirror image appears to suggest an erotic interest in the customer looking down on her.

Now, Manet shows some fascination with women of the “demi-monde” – think of Olympia (Figure 2). But he also depicts them – as well as other women of different social background – with respect if not admiration. See, for instance, The Waitress (1879) in Figure 3, and in The Balcony (1868) his painter colleague and model Berthe Morisot, a respectable woman of upper-middle class and (later) wife of his brother (Figure 2). Perhaps his most famous portrait of a beautiful young woman – Spring: Jeanne (1881) in Figure 3 – was exhibited next to the Bar in the Salon of 1882. The fact that she also was an actress with “loose” moral standards adds nothing to the interpretation of the painting.

It is at least not obvious what the possible background of casual prostitution of the barmaid Suzon adds to the understanding of Manet’s intentions in painting the Bar.

Figure 3: The Waitress (1879) and Spring: Jeanne (1881)

The point is: Taking the painting – considered as a final “testament” of his art – out of the wider context of Manet’s work and placing it in a narrower context like Parisian (male) amusement is bound to misrepresent the complexity of the painting.

As Flam (184) states, the painting is first of all a “poetic image”, although Manet choses the setting of a bar at the time.

Champa, I think, finds an adequate formulation for this aspect when calling the painting Manet’s “private art history” (106). This final masterpiece tries to look back on about 20 years of work in which Manet’s strives to position himself in the tradition of painting while questioning established norms. There are numerous citations in the Bar of earlier works – Christ with Angels, Olympia, The Balcony, Breakfast, At the Cafe, to name a few – but the “12 views” do not exploit these references by placing the painting into a more systematic “private art history”.

Considering the aim of the editor to show-case different approaches in their interpretation of the same masterpiece, this limitation might make sense.

In view of MyManet, however, it also demonstrates that there is no convincing interpretation of a masterpiece which does not interpret it in the context of relevant other works by the master.

Manet’s realism and the mirror

All interpreters – including myself – are fascinated by the puzzle of the image in the mirror.

Everybody agrees that the mirror is not correctly presenting the reality of the scene at the bar. But how the distortions are to be explained gives rise to very different interpretations.

The most obvious “mistakes” are that the image of the back of the barmaid in the mirror to the right would – in reality – be hidden behind the barmaid and that the gentleman looking into the eyes of the barmaid in the mirror would also be hidden. He would actually stand before the barmaid at the counter in the position of the viewer.

Less obvious but disturbing when trying to “read” the spatial relations is that the reflection of the counter with its marvellous still life seems to be floating in mid-air. At the left side, there is no floor and no balustrade indicating the space in front of the bar where the viewer would stand. We are looking into an “abyss” (Flam), and the items on the counter are not correctly reflected in the mirror. We have a clear view to the opposite side of the hall with a balcony full of visitors, some of them looking to the left to the action on stage, others looking back at the barmaid or at the viewer’s back.

Manet is playing games with us, again.

The “mistakes” are certainly intended raising the question of their meaning.

One issue concerns Manet’s realism. As Champa (108) puts it:

“Like all of Manet’s best works the Bar looks right before it looks wrong, and the letter sensation never completely subverts the former.”

Manet is not showing a convincing illusion, but he is not presenting the reality of the scene either. According to Flam (168) the “spatial contradiction … calls into question the very notion of realism.” But this is not new, we have seen this violation of naturalistic representation, especially of the laws of perspective, already in the Luncheon on the Grass.

As to the adequacy of depiction, Manet’s realism – in view of MyManet – is better understood as “reasoned imagery” following a practice of engravings and lithographs in science (see Post 10 and 11). Here, realistic depictions of, say, a flower may show the flower and the fruits or different stages of growth in the same picture. Realism is not (only and always) what you see but what exists. And Manet’s realism aims at representation in a social space constituted by the gazes within the painting and with the viewers outside; it is a realism of relations.

Flam (169) describes it as going beyond “surface realism” or – citing Baudelaire – “not only of seeing, but seeing of meanings”. This realism allows Manet, according to Flam, to introduce the mirror image as depiction of an “interior monologue” (171) or of something the barmaid is daydreaming.

In this case, the gentleman in the mirror does not exist in front of the barmaid and his absence (being seen only in a dream) rather than his impossible presence (reflected in violation of optical laws) poses the starting point for interpretations.

Both Collins and Flam emphasize, moreover, that Manet’s first sketch of the scene is more naturalistic (see Figure 4), and that the changes Manet made in the process lead to a more formal or poetic composition and an iconic symbolism reminding of Virgin Mary.

Figure 4: A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (sketch) (1881)

Similarly, Driskel (146) points out that the final version of the Bar reminds of Dead Christ with Angels (1864) in its religious symbolism while Christ Mocked by Soldiers (1865) rather resembles the sketch showing the illustration of an historical event transposed into contemporary reality (albeit in Manet’s studio – Post 14 and 15).

Thus, already early in his realism Manet moved intentionally between a more natural and a more symbolic “reasoned” imagery.

And he does it without falling into the trap of the (false) alternative of abstract formalism versus relativistic subjectivity which Richard Shiff seems to assume in his introduction. In his words: the alternative between sincerity following rational, verbalized aesthetic principles, or morality, sensibility and inner psychological states (8). Manet’s way out – according to Shiff – is cultivating a style of ”technical abbreviations” or a personal “visual rhetoric” (9).

In view of MyManet, this is not capturing Manet’s realism.

Quoting from Post 11:

Lüthy describes Manet as taking the “position of an impossible Third”: The position of a “realistic formalism”. He combines reflective imagination with a creative practice which is not “representation” of reality but an experiment. “In this experiment questions of form and content, artificiality and realism merge into one another”

(2003, p.116).

This experimental approach is beautifully demonstrated in a more recent analysis by Thierry de Duve (1999). Not included among the “12 Views”, his contribution is the exception mentioned above.

Duve shows convincingly that the “12 Views” and earlier attempts to resolve the spatial inconsistencies in the painting by the juxtaposition of different positions of the viewer are inadequate. Supporting his argument with diagrams, he rather suggests that the customer is imagined in two different positions as he moves to the counter. First, he is seen only in the mirror – like in Manet’s earlier sketch (Figure 4) – coming from the right outside the perspective of the viewer. Then, in the studio, Manet turns the mirror at about a 20 degree angle forward on the right side. Now, the customer moves into the position of the viewer in front of the painting while his mirror image and the mirrored barmaid become visible to the viewer as in the final version.

Thus, Manet is juxtaposing two moments in time by manipulating the spatial arrangement of the mirror.

In view of MyManet, the beauty of this interpretation is not so much the solution of the spatial puzzle. That Manet did play games with the laws of perspective, we know from the analysis of Luncheon of the Grass already. The attractiveness is more in imagining Manet as an active, realistic experimenter in his studio rather than, say, as an inventor of dream worlds of the barmaid floating in a mirror!

This is not to say that interpretations starting from the surreal character of the mirror image and proceeding to socio-historic and/or psychoanalytic scenarios are wrong or illegitimate. Manet was probably well aware that he encouraged such interpretations. But on a first layer of interpretation, we can start with “spatial games” within the painting and with the position of the viewer.

Or as Champa puts it: We need not assume the role of “socially sensitive” scholars who interpret Manet in ways that “make of what he doesn’t do the implied true meaning of what he does” (105).

Or even better: In view of MyManet, we can be “socially sensitive” interpreters but remain on a level of interpretation of social space without resorting to deeper psychological or sociological “stories”.

How?

Obviously, by applying Manet’s scheme successfully to A Bar at the Folies-Bergère! This we will show in the next post.

But why introduce the mirror in such a prominent role if it only creates ambiguities for a realistic reading?

The mirror has a long tradition in the history of painting and serves different functions:

The mirror shows what cannot be seen from the viewer’s perspective or from the perspective of a figure in the painting. It shows what some “other” person can see from inside or outside of the painting. This includes the face of the person looking into the mirror which can only be seen (frontally) in the mirror by the person looking.

In a sense, a painting – or the person looking out of the painting – functions in the role of a mirror.

We develop the image of ourselves looking into the “mirror” provided by the faces of other persons, or: by Seeing Being Seen (Post 24).

In this function, it plays also an important role in the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan. Especially Collins (131) provides some valuable insight into the role of Lacan’s “other” in the interpretation of the Bar (and by implication for Manet’s scheme).

But Manet supports and, at the same time, subverts such interpretations. The barmaid is not functioning as a “mirror” – Seeing Being Seen – for the viewer; her gaze is somewhat diverted.

The mirror behind her shows the customer in the position of the viewer, so who is mirrored?

A problem with mirrors is that they do not show reality but a reflection.

As we have seen in Post 12, this poses already problems in the case of a self-portrait.

A mirror parallel to the picture plane and not showing the painter and/or the viewer, obviously violates physical reality.

In Figure 5, we see an example by Manet’s colleague and friend Gustave Caillebotte, At the Café (1880). Caillebotte is also a realist of sorts, although he joined the impressionists, and he supports a realist interpretation by showing the reflection of the gentleman in the café pretty much where the viewer would expect seeing it in the mirror – covering the image of the viewer. The viewer tends to place himself or herself slightly to the left. And Caillebotte supports this shift by letting the gentleman looking to the right passed the viewer. He is not catching the gaze of the viewer as a “mirror” or as an engaging subject! Manet’s barmaid makes the viewer wonder if she is “seeing being seen” – if not hoping that she redirects her attention sympathetically like in the mirror image.

Figure 5: Mirror images by Manet and Caillebotte

In the Bar, it is telling that Manet introduces ambiguities on both sides of the mirror plane. The items reflected in the mirror do not correspond to those in front. Even more puzzling:

- the barmaid appears in the pose of Virgin Mary (Driskel) or Dead Christ with Angels avoiding the viewer’s or customer’s gaze but is depicted with a tight seductive waist and low neckline;

- her mirror image seems to be more receptive to the sexual wishes of the costumer but her fuller waist and somehow sympathetic appearance is reminding rather of Manet’s Dutch wife Suzanne. Flam (166) also points out that the barmaid has her hair strictly pulled back like bound in a ponytail while her mirror image has more girly loose strains.

But, when Manet is not confronting a layer of reality – the barmaid and the still life in front of us – with a layer of “deep” or “absent” meaning of phenomena in the mirror, what else is he doing?

Besides having the viewer search the painting for some cues as to where his or her own position could be and looking into the abyss in the left side of the mirror?

What is the “message” of the couple in the mirror if not reflecting some reality in front of the painting?

Advancing an own “twist” to the interpretation of spatial inconsistencies, I suggest taking a fresh look applying Manet’s scheme.

Seeing you in about two weeks! (PS: Still recovering from Covid…)