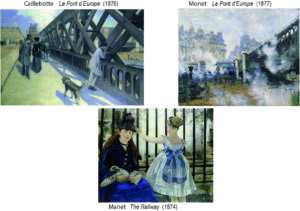

Manet is putting his figures “on stage”, so: how realistic is the scene unfolding on the canvas?

In our view on Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergére, we have seen surrealistic elements questioning his self-claimed realism (Posts 25-27). He clearly arranged the basic scene in his studio and wanted the arrangement to represent the situation in the Folies-Bergére as realistically as possible. He even hired a barmaid from the place to model for the central figure. But then he experimented with the mirror violating optical laws within the painting with impossible reflections undermining a realistic interpretation.

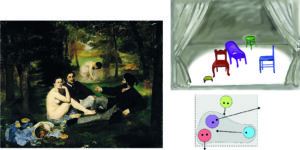

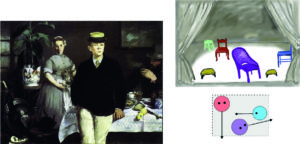

Figure 1: Luncheon on the Grass “on stage”: The positions of chairs

Let us follow up on the image of a stage like in Figure 1. The play given is Luncheon on the Grass, and – since Manet is avoiding telling a “story”- let us assume the curtain has just opened and we only see the positions for the actors (call them: First, Second, Third and Other) marked by different chairs. In Figure 1 the red chair is placed for the First (the female nude), the blue chair expects the Second (a male) and the violet chair kind of looks off stage as the Third (another male), and the woman onlooking from the back – the “Other”- will sit on the green stool. A little bench (yellow) is added on front stage indicating the typical still life. The chairs are positioned and turned following the composition according to Manet’s scheme indicating the direction of gazes.

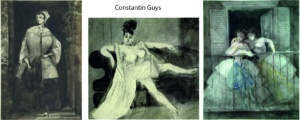

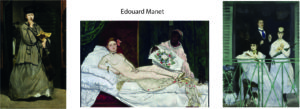

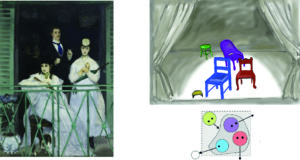

In Figure 2, the Luncheon is compared with three major paintings discussed earlier which Manet submitted to the Salon. In 1865, Christ Mocked by Soldiers was exhibited together with Olympia (painted already in 1863), Breakfast in the Atelier (1868) and The Balcony (1869) were presented together in 1869. Manet clearly wanted to make his claim as a leading painter of his time with those paintings.

For each painting, a little stage indicates the position of the chairs, and each painting is reduced to a little diagram describing the gazes of the central figures. The diagrams contain the four gazes, except Breakfast and Christ Mocked where the background figures – the green stools – are missing. In Breakfast the prominent white flowerpot may stand in for the fourth figure.

Figure 2 a-d: Variations of Manet’s Scheme “on stage” and reduced diagrams

a) Luncheon on the Grass (1863)

b) Christ Mocked by Soldiers (1865)

c) Breakfast in the Atelier (1868)

d) The Balcony (1869)

As the diagrams reveal, Manet is varying a basic scheme by changing the direction of the gazes and moving the position of chairs on stage, creating different painterly challenges:

On one level, these changes prompt changes in the composition, because the figures have to be balanced within the frame of the painting while their gazes produce their own “force fields” or a social space affecting the compositional balance.

On another level, we might link the composition to (possible) content.

Luncheon (Figure 2a) meets the viewer with a friendly direct gaze of the nude as First (red). Although the viewer is not directly invited to join, there is no embarrassment or rejection. The composition is open to the wider setting, even bridging to the viewer with the still life in the front. The fourth figure in the back (the “Other”; green) mirrors the position of the viewer, who might as well imagine standing there. We see a quite harmonic scene, although on closer inspection, we have the disquieting feeling that there is a potential for disruption, because the triad is not effectively communicating within the group and the onlooker is somehow looming too large. The diagram shows the tension between the – unexplained – inner divergence of the triad. Stability is induced from outside through the explicit relation to the viewer and the anchoring role of the figure in the back (more in Post 7-9).

Christ Mocked (Figure 2b) presents Jesus surrounded by figures emphasizing his vulnerable position as a human among humans (see Post 14). As the diagram shows, now the Third (purple) is placed in the centre, the First (red) is moved further back, and two figures create the unity of the group gazing at Jesus in the role of the Second (blue). The figure looking from the back at the group (green) is missing, unless we interpret one of the soldiers to the left as doubling in that role (like in The Drinkers by Velazquez; see Post 4). But there is a possible reason why Manet chose to introduce two Seconds. Placing the Third in the centre and the First behind him uses up the space on the narrow “stage”. Placing an onlooking other person behind the First would great a depth of the “stage” distracting from Christ. Thus, the back is closed off by a dark “backstage”, instead, pushing the figure of Christ closer to the viewer. The alternative view by the “other” is now taken by the other Second up front.

The interpretation of the gaze of the Third is no mystery in this case. Christ is obviously turning his gaze toward God, the ultimate “authority”, who also seems to illuminate the stage from above. And Manet did not forget the still life, here in the very front to the right. (The basic composition seems to be “stolen” again – see Post 14.)

Breakfast (Figure 2c) puts the Third on front stage almost into the viewer’s space: the young man is looking beyond the viewer as a youth might look into his future, detached from the male (“father”) and female (“mother”) figure in the middle ground. Since the young man is modelled by Manet’s son Leon, it is fair to assume that Manet was well aware of the uncertainties belabouring the boy in his passage to adulthood, created by the lack of an accepted “authority”. The painting is regarded by art historians as his most “enigmatic” (Rubin), although seeing it as variation of Manet’s scheme takes away much of the mystery (more in Posts 18 and 19).

Manet is experimenting moving the Third (purple) now frontstage even slightly before the still lives to the right (lemons) and the left (theatre requisites and the cat). The First (red) is again placed in the back. With the youth frontstage, this creates now an “empty stage” in the middle only partly occupied by the table. (By inserting his monogram on the carafe in the “empty” centre, Manet is certainly being ironic.) The Second (blue), the gentleman to the far right, has now to “fill the gap” by directing his gaze across the “stage”.

Comparing this again with Luncheon, we see that Manet is exaggerating a task the Second had already in the previous painting. There, looking between the other two, he was located somewhat out to the right, the outstretched arm helping to integrate the group. The triad is even more diverging than in Luncheon. Manet is “zooming in” on the triad and, at the same time, drawing the figures further apart. As in Christ Mocked, the onlooking “Other” (green) is missing, although the somewhat unmotivated and too large white flowerpot in the back to the left might be seen in that role. Rather than including the view from the back, the wall of the atelier closes the room toward the back (the “past” of the youth) pushing the young man even more toward the viewer or his future. The “enigmatic” and even unsettling experience of the viewer is certainly enhanced by the pitch-black coat of the Third almost punching a hole into the “empty stage”, with a black cat in the dark middle-ground, no less, reminding of Olympia.

The Balcony (Figure 2d) seems to violate the scheme, but Manet chances another experiment (Post 20). The Second (blue), the figure originally assigned to the role of integration within the painting, is now sitting front stage and looking outward to the left. But this figure is focusing her attention on somebody (or some event) which is unrepresented (white circle) but very present through the intensity of her gaze. She is not gazing “beyond” the scene implied by the painting (like a Third) but stretching the social space outside the picture space. The role of the Third (purple) is occupied by the gentleman behind her. The First (red) is standing shyly next to her (not to distract from the intensity of the Second). The scheme is completed by the boy (green) looking from the back barely noticeable in the dark background. (Again, all figures are identified as specific persons; prominently, Berthe Morisot – see Post 20).

The intense outward look of the Second including someone not represented creates a great tension, both on the level of composition and on the level of content.

On the level of composition, Manet copes with it by rather dramatic means: boxing the whole scene in on a balcony with glaring green shades and railing and closing it off with the darkness of the room in the back. The “stage” shrinks to hardly more than 2qm.

On the level of content, Manet allows the Second to stretch the setting of the triad out into public space. The entire scene on the balcony is floating on the border of the (dark) private space behind the figures and the public space in front of them – the audience. The viewer is engaged by the gaze of the First, but even more captured by the daring movement of the triad out and into open urban space – or the audience of the theatre.

The theme of Manet’s scheme has again changed and with it the content of the formal roles.

In Luncheon we found a rather intimate scene lacking, however, internal relations; in Christ Mocked the religious tradition promises guidance (although the vulnerable figure of Christ has to look up for it); in Breakfast any guidance for the youth looking into an open future was uncertain; and in The Balcony the integration of the triad is questioned by turning to others in public space. Moving the “chairs” on the “stage” opened for Manet new avenues for interpretation – form and content interact.

The analogy of the theatre with changing positions of chairs helps to explain the somewhat strange lack of movement or activity in his paintings. Manet focuses on relations between the actors before they start enacting a “story”, or as they pause to acknowledge the presence of an audience. Manet was over his entire career in close friendship with prominent writers like Baudelaire, Zola, and Mallarmé, and kept close relations with the theatre world. He was perfectly aware what it means to set the stage, position the actors, and create an atmosphere quite independently from the general plot about to occur.

Between the Luncheon in 1863 and The Balcony in 1869, there are three other multi-figure paintings which seem to be exceptions to Manet’s scheme: Olympia (1863), Dead Christ with Angels (1865), and The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867). We have seen the influence of Manet’s scheme on these paintings in Post 17, 15, and 21, respectively. After the Prussian-French war 1870-71, we find a number of important works (The Railway 1873, Argenteuil 1874, Boating 1874) which seem to reduce the scheme to a relation between two persons. I will return to these paintings in later posts. The unfulfilled love with Berthe Morisot (whom he first met in 1869), the French-Prussian War, and the impact of his Impressionist phase (at least partly motivated by Morisot) may have distracted him from experimenting with his programmatic scheme – we don’t know. But then the scheme re-surfaces albeit in subtle ways – most clearly in Nana (1877) and At Pere Lathuille’s (1879) – and emerges, as we have seen (in Post 25 and 26), as a hidden “painting not painted” in A Bar at Folies-Bergère (1882).

In Figure 4, I try to picture the “stage” of A Bar at Folies-Bergère. The mirror might turn into a transparent background behind which we can see the chairs of figures in the mirror while the chair of the barmaid (as the Third) is placed on front stage. Such transparent screens were already in use on stage at the time. Hubert Gassner (2016, p193-204) has offered a fascinating analysis of Manet’s studies and the final portrait of his friend and actor Jean Baptiste Faure (1877) (Figure 3). Manet tried to capture the actor in the role of Hamlet seeing the ghost of his father. The study suggests that the actor sees the ghost – very likely projected on a transparent screen next to the viewer (or Manet himself) throwing a shadow onto the stage while the audience is looking on from behind. In the portrait the viewer and the screen are in front of the picture space, in the Bar a mirror is behind the barmaid showing the audience and the viewer in front. Both “Hamlet” and the barmaid are looking at something (or someone) which is not quite real.

Figure 3: Portrait of Jean Babtiste Faure in the Role of Hamlet

by Edouard Manet (1877)

Figure 4: Setting the stage for A Bar at Folies-Bergère

As the little diagrams show, the figures assume their “proper” role only in the Bar “unpainted” as I proposed in Post 25 and 26.

In this image, associations with modern concepts of theatre arise, I think, quite unavoidably. And it is certainly no coincidence that Manet’s closest friend at the time was the writer and critic Stéfane Mallarmé who was an influential reference in the development of modern theatre for a generation later.

Looking back to the works painted after Luncheon with the image of the “stage” helps to make a central point of MyManet: Not only can Manet’s scheme be abstracted from a process leading up to Luncheon on the Grass, one of Manet’s most famous paintings, but it is a more general scheme which influenced the following multi-figure works including his final masterpiece.

Another feature of his work is suggested by the image of a stage: there is a dark backstage, hidden from the viewer, from where actors enter to take their positions, and there are some unsettling surrealistic elements in his compositions which question his realism.

This “dark side” of Manet, I would like to illuminate in the next Post.

See you in in about two weeks!