The “12 Views” of A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (Collins 1996) discussed in the previous Post 25 had two topics in common:

the role of the barmaid as picturing Manet’s view of women in Parisian society and the spatial inconsistencies or violations of perspectives caused by the mirror.

But there are other aspects which are neglected or featuring less prominent in the discussion.

Let us consider some of these aspects taking a fresh look at the painting

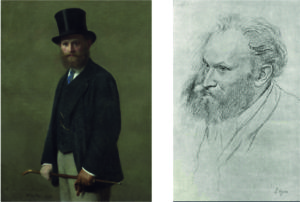

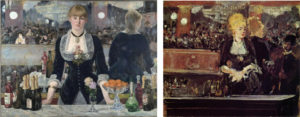

and a sketch in Figure 1.

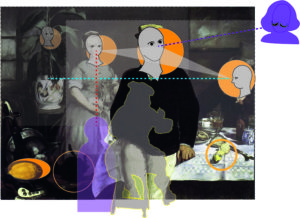

Figure 1: Edouard Manet

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) and Sketch for A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1881)

First question:

Disregard for correct perspective is not a new feature in Manet’s paintings.

But why using a mirror to close up the background rather than a curtain, a wall or a dark space or some other partitioning as in previous paintings?

Staging the figures in a limited “flattened” space – in a “puppet theatre” – and leaving the viewer in a shifting position in front of the scene – that is a feature which is characteristic of Manet’s scheme as proposed in MyManet.

But, using a mirror – which is typically used to open up a space – to close off the scene in the back is counterintuitive. We should think that it simply does not work. It does in this painting.

The viewer is fully aware that the barmaid is standing in a very narrow space between the bar and the mirror. Manet is moving the balcony on the left side forward like in a magnifying mirror, as Flam (166) observes, and he uses a loser, impressionistic brushwork painting the background.

The black back of the reflected barmaid effectively closes off the view on the right side (an effect not achieved in the sketch!).

Using the mirror in ways obviously violating optical laws creates problems for his realistic style.

Why is Manet inviting doubts about his realism?

Second question:

The barmaid reflected in the mirror seems to be a different woman.

The mirror image has rather loose hair while the barmaid has her hair tightly pulled back. Flam (166) even suggests that she might have a ponytail. The cheeks of the mirror image seem to be rounder, her waist somewhat fuller, and her posture leaning forward and more attentive and friendly to the customer – if not inviting and “eager to please” (Flam 167).

But, does she look more like a casual prostitute than the barmaid confronting the viewer with her tight waist and low neckline, as many interpretations suggest?

Or is this a view following from an assumption that the gentleman in the mirror surely must be a potential customer?

As Lüthy (2003, 164) observes: In interpretations that follow T.J. Clark’s focus on prostitution in Paris at the time, it seems that “the interpreter approaches Manet’s painting like the customer the counter” trying to find out whether she is a prostitute or not (own translation).

Is Manet – perhaps critically – presenting the “male gaze” or is he playing with the expectations of the viewer?

Third question:

The viewer seems to be standing at a comfortable distance from the barmaid

(about 2m following Flam).

However, the gentleman in the mirror is uncomfortably close leaning over the counter and looking down into the eyes of the woman. He is scaled a little too large and looming in the upper corner at a position which does not correspond to any possible place in front of the barmaid.

It is not even clear whether she is returning his gaze or looking somewhere through and beyond him. (Both facts are somewhat at odds with the interesting interpretation of Duve – see Post 25.)

In the sketch for the Bar in Figure 1, a smaller customer is positioned lower and looking up to the barmaid looking down on him. Their gazes in the mirror seem to meet. The barmaid herself is looking to a place to the right of the viewer where the gentleman actually may stand.

Why the changes?

Why is the barmaid in the final version looking toward the viewer but avoiding eye contact?

Why is the mirror image of the assumed customer now moved into an implausible position in the upper right corner?

Fourth question:

In the final version, the left side is on closer inspection a confusing collage of detached elements:

– The balcony is too close compared to the right side (compare also the width of the columns);

– the legs of the artist on the trapeze are too small and certainly not above the stage;

– the counter with bottles in the mirror is floating in the air;

– the balcony appears to be zoomed in to avail a better look at the people on the other side.

Art historians have identified the three women sitting around an empty chair, two looking toward the stage to the left, one seems to look at the viewer.

A fourth person, a gentleman with a black moustache, looks similar to the gentleman in the upper right corner and he seems to direct his gaze at the barmaid (or the viewer’s back).

Manet is clearly citing people he knows. We see a “little cabinet of perspectives” (Lüthy p.178) in the focus of the left side.

How should we explain this grouping and the direction of their gazes?

So, what to make of these questions in view of MyManet and applying Manet’s scheme?

As a starting point, the painting has been described as a “testament” by several authors.

If it is true that Manet is looking back and citing many of his important paintings, and

if MyManet is capturing with Manet’s scheme some relevant feature of his work,

then we should find aspects of his scheme in the composition of the Bar.

On first sight, this is not really promising:

There is only one figure in the painting – and two or more reflections.

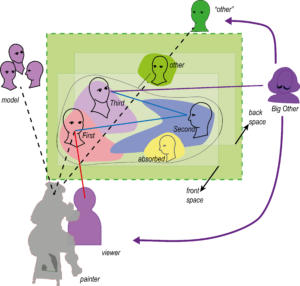

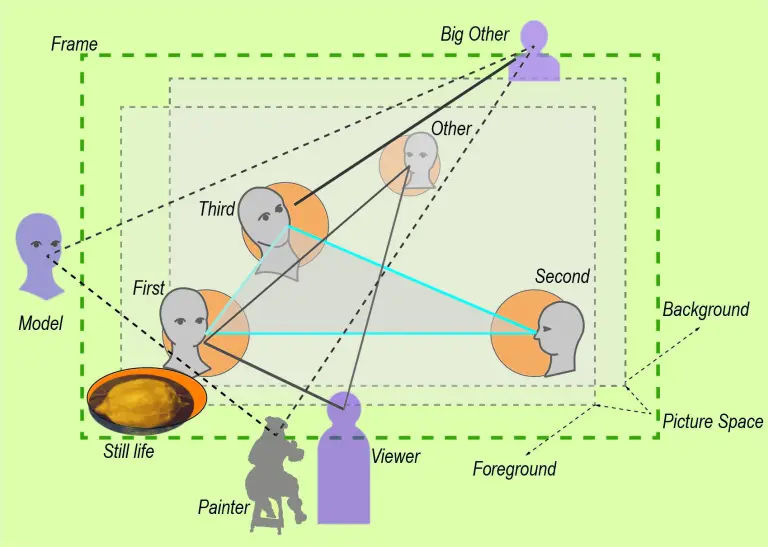

Manet’s scheme as developed in discussing the Luncheon on the Grass (1863) provides for four positions and gazes within the painting (see Post 9 and 24):

The First – looking at the viewer:

“seeing being seen” by the viewer

The Second – looking at someone within the picture space supporting the internal “stage”:

“being seen seeing” by the viewer

The Third – looking out and beyond the picture space:

“seeing without seeing being seen” by some other

The “Other” – looking from the back:

seeing from a position other than the viewer.

The barmaid is clearly puzzling since she is not really looking at the viewer.

If anything, she is gazing at some unidentified spot beyond the viewer – seeing without seeing being seen.

This would qualify her for the position of the Third.

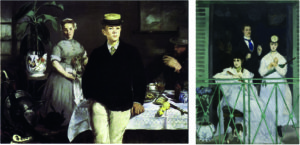

An example of this variation of the scheme we found in Breakfast in the Atelier with the young man standing very up front and looking past the viewer (Post 18 and 19).

The couple reflected in the mirror would have to take the role of the First and the Second.

But that seems quite a stretch for the scheme.

The woman in the mirror as the First (seeing being seen) would use the mirror and look backward at the gentleman who takes the role of the viewer in front of the painting.

Conceivable; however, this leaves us without the Second.

The gentleman in the mirror seems to meet the gaze of the barmaid in the role of the First, establishing a relation between her and the viewer represented by him.

For the role of the “Other”, looking at the scene from the back, he is clearly much to close to her.

The ”Other” could be identified readily in the mirror on the balcony to the left.

Especially the gentleman with the moustache, as Flam (166) describes him, is literally looking from the back onto the scene.

Thus, to satisfy Manet’s scheme we need an interpretation for the missing Second.

(Somewhat like Sherlock Holmes and the dog that did not bark.)

For a solution, we consider the role of the couple in the mirror again.

What if their role is just to provide the viewer with a clue on how to “read” the painting and to see

the painting that Manet did not paint ?

What is the clue?

Manet clearly invites the viewer to take the position of the gentleman in the mirror and to see what he is seeing.

Basically, that means that the entire scene is turned around and the reflected viewer is now in the position of the “real” viewer looking into the eyes of the barmaid who is gazing at him. The “real” barmaid will turn into the mirror on the left side looking toward the back. The “real” viewer will take a position in the mirror to the left, only that – keeping his distance from the barmaid – her reflection will appear more behind the barmaid in the centre.

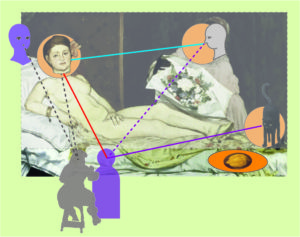

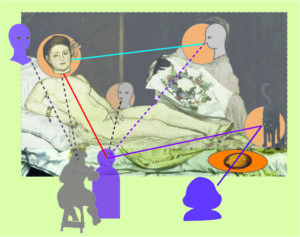

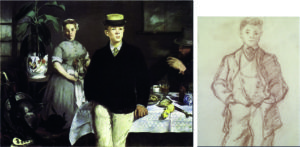

The new “painting not painted” would look somewhat like in Figure 2 !

Figure 2: “The painting not painted”:

The original painting and the Bar seen with the eyes of the man in the mirror

The “new” painting is actually based on mirroring the original painting vertically,

thus, it combines a mirror image – like in a lithograph, an operation quite familiar to Manet – with the turning around of positions.

Some “photoshopping” is also needed. The waist of the barmaid is adapted and a ponytail introduced (following Flam). Most importantly, the face of the friendly barmaid has to be inserted. I took the liberty of utilizing the face of Manet’s favourite model of his earlier period – an undated portrait of Victorine Meurent.

But why using a reflection of the painting?

Unlike the small angle assumed in Duve’s interpretation (see Post 25) turning of the mirror – we now assume an almost 180 degrees turning of the painting and moving the position of the viewer. Duve wants to explain the positions of the two figures within the painting (barmaid and customer) keeping the place of the viewer fixed. This is still a meaningful layer of interpretation.

Given the positions, however, MyManet tries to explain:

Why are the mirrored figures painted as they are?

– clearly not as realistic reflections of the figures assumed in front of the mirror, as Duve implies.

Now, if we apply Manet’s scheme to the “painting not painted” – it works!

In Figure 2, we see the missing Second now impersonated by the (imagined) former viewer.

The barmaid is perfect in the role of the First leaning slightly forward and engaging the viewer.

The “Other”, the gentleman on the balcony, has switched sides, but is still onlooking.

The Third, the mirrored barmaid, in this variation is looking somewhere off to the back. She is “seeing without seeing being seen by some other”.

This is a variation in the direction of the gaze compatible with the scheme. And we still have the original barmaid with her evasive gaze in front of us (reminding us of the Third) when we – as viewer – imagine looking with the eyes of our reflection in the mirror.

Revealing the role of Manet’s scheme in the composition supports interpretations of the painting as a “testament”. It is not only citing previous own paintings but also revitalizing and creatively developing a basic compositional scheme.

Already since Olympia (1865) – as demonstrated in Post 17 – Manet has applied variations of the scheme with fewer figures. In the 70ies, after The Balcony (1868), he has used the scheme only partially in paintings with two figures (for instance, Nana). We will have a look at the major paintings in the 1870ies in following posts to see the continuing influence of the scheme.

Here, in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Manet goes one step further and ingeniously – so the view of MyManet – applies the scheme with only one central figure and with a counterintuitive use of a mirror to set the “stage”.

The view that Manet is searching in the Bar for a new and innovative variation of his scheme can explain some of the changes from the study to the final version (Figure 2).

Moving the barmaid in the centre and giving her this famous avoiding gaze is designed to radicalize the attempt from Breakfast in the Atelier placing the Third front and centre – this time as the only “real” figure.

Already in the Atelier, we interpreted the gaze of the young man as looking into his open future. The role of the Third, more generally, signifies in the scheme the orientation to some “authority” outside the picture space.

Both aspects gain obvious significance in a painterly “testament” by a painter expecting his death.

With the gaze of the barmaid directed somewhere passed the viewer, the right side of the study (Figure 4) does not work anymore. Manet had to find a new solution which preserves credibility as a realistic painting, at least on first sight, and which allows for the application of the scheme to the other figures.

The result is the juxtaposition of a painting with a “painting not painted”.

The study and the first impression of the final version do not conform to the scheme,

but a viewer accepting the invitation to imagine looking through the eyes of his (or her) “impersonator” in the mirror will have the benefit of seeing the scheme – an important element of his “testament”.

But there is another clue on the left side. One is tempted to say, for those of us (including me) who do (or did) not readily recognize the clue on the right side pointing to the presence of Manet’s scheme.

Interpreters typically focus on the figures on the balcony only as representing friends and colleagues.

The “little cabinet of perspectives” (Lüthy p.178), however, can also be seen as a citation of Manet’s scheme!

The empty chair creates a space distinguishing the three adjoining figures.

The figure to the left reminds of Berthe Morisot in The Balcony posing for the Second (although she has been identified as another friend of Manet’s);

the figure to the right is citing a painting by Mary Cassat, and she is using her opera glass to stare beyond the picture space – a candidate for the role of the Third;

the woman in the next row (clearly accentuated by the empty chair) is looking straight at the viewer – taking the role of the First.

The gentleman to the far left plays already the role of the “Other” but – given his reflection – he can also be seen as doubling as an “Other” in the “little cabinet”. (The lady and the gentleman could change roles as First and “Other”, but I think that the empty chair is meant to join the lady to the triad.)

The complex composition is summarized in the diagram in Figure 3:

Figure 3: Diagram of the scheme in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

On the left and centre, now we see Manet’s scheme with the roles of the First, Second and Third. Additionally, the shifting position of the viewer is indicated. In the original, the viewer is induced to move slightly from the centre to the right trying to align with the mirror image within the painting. In the “painting not painted”, the viewer is motivated to shift to the left as indicated in the diagram.

This shifting from outside to inside and from right to left will motivate the viewer (if he or she is trying to solve the puzzle) to look “from the side” on the level of the mirror plane – a position supporting identification with the Second and establishing the picture space.

On the right side, we see the “little cabinet” reminding of the scheme and the “Other” doubling inside and outside the painting.

Besides the painterly challenges of using a mirror as a background, Manet has solved the problem of staging his 4-figure scheme within a painting featuring essentially one figure.

Two questions (1 and 2) are still open from our list above:

Manet is playing games with the “male gaze”.

In view of the “painting not painted”, is there a clue that there is also a “female gaze not painted”?

And:

Manet seems to put into question a realistic interpretation more radically than in any previous painting.

This is especially troubling in the case of the looming face of the gentleman placed in the upper right corner.

Should we reassess Manet’s self-claimed position as a realist?

Good questions, but let us address them in the next post.

See you in about two weeks!

and Venus of Urbino by Titian (1538)

and Venus of Urbino by Titian (1538)