Velazquez has demonstrated for us (in the previous post) that there is a range of different directions the gazes of persons will take – and how these gazes structure the social space within the painting and with “unrepresented” persons outside.

Time to have a more systematic look at these gazes and their meaning.

In some cases, the proper classification may be disputed, but this is not relevant for the following.

Since not all faces or gazes appeared in all three examples and some appeared more than once, we might ask:

Question 3: How many gazes or persons are needed as a minimum?

Or to be more specific:

If the “painting of painting” is the theme, how many and what kind of gazes are needed within the painting to communicate with a certain number and kind of persons assumed outside the painting?

The answer to this question will lead us into some rather theoretical territory – so, I hope for your patience, and hold on tight!

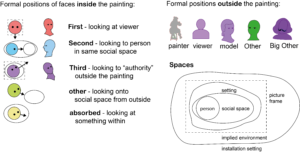

In Figure 1 we find an overview of the faces in the diagrams (see Post 4):

Figure 1: Formal positions and faces in Velazquez’ paintings

Actually, the overview presents not all the cases we might like to distinguish in MyManet:

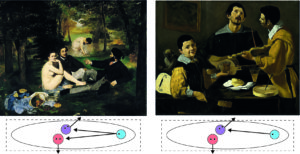

The triad of persons, which are at the centre of Luncheon on the Grass (Figure 2), is not an obvious element in Velazquez’ examples. The triad comprises a gaze (red) to the viewer (the nude), a gaze (blue) to the members of the group (man to the right), and this strange gaze (purple) directed outside the painting (second man).

All three gazes appear in each example of Velazquez, but not in a specific arrangement and they are combined with other gazes.

In MyManet, I want to identify the members of the triad with specific names and formal positions:

The First

The First is making the essential contact with the viewer outside the painting.

As in The Drinkers, this may be more than one person. But then we may conclude that this is suggested by the theme – the joyful group – rather than needed in a more general scheme.

In The Little Cavaliers, we find also two Firsts (red) in the centre groups engaging the viewer. A third person to the right, looking towards the viewer, may be gazing toward the viewer accidentally, not really trying to engage the viewer.

In other paintings, we will find more of these “accidental Firsts”, especially, in paintings with larger groups. In some cases, the person looking toward the viewer will be so “distant” in the middle- or background that the engaging effect does not arise.

A special case is the viewer entering – as it were – the painting and appearing as a backfigure in the foreground (see Post 3). We might say that engaging the viewer is so effective that the viewer steps into the scene and takes the role of the First. An additional First is not needed to achieve the engagement.

In terms of Fried’s “facingness”, the picture as a whole has attracted full attention.

In a diagram we could depict the backfigure as a First (red) from the back (without eyes or face).

For reasons discussed below, I prefer to show the viewer as backfigure within the painting to keep the role of the First distinct. Manet does not use backfigures in his paintings. (With rare exceptions e.g. in the Masked Ball at the Opera with a Polichinelle from the back appearing on the left side.)

The Second

The Second has the role of creating the social space by looking at the other members of the group.

There may be more than one group, like in The Little Cavaliers, so we expect one of them in each group and social space. In some cases, the Second may be seen from the back (no eyes or face), but then we interpret the position to be “accidentally” turned away from the viewer. The position is not specifically calling for the identification of the viewer to take this position and look at the scene through the eyes of the Second.

The Third

The Third is acknowledging the existence of some external “authority” with his or her gaze.

The Third has a role that is crucial for Manet’s scheme – and it is, I think, one of the reasons why Manet is admiring Velazquez.

The best example, among the three paintings from Velazquez above, is Las Meninas with the Master himself (and some of the other figures) looking at the royal couple entering the scene. As indicated previously, all interpreters agree that the painting is celebrating the royal institution, not just the royal couple. And we should add that the dominant figure of the painter himself also aims to emphasize the importance of painting as a cultural institution, not only Velazquez’ personal success as royal painter.

This reference to an external “authority”, we see also in The Drinkers in the gaze of Bacchus; it is not so obvious in The Little Cavaliers, where the gazes (purple) out of the painting may be “accidental” to persons which just happen to be outside the picture frame.

The triad – First, Second and Third – is an essential element of MyManet, i.e. my view of the hidden meaning in Manet’s compositions.

It is not the only one, as we see shortly. But I like to remind you of the etching of the puppet theatre – shown already in Post 2 – where the triad is prominently on stage. (There is a fourth figure, perhaps Polichinelle subdued by the police officer? And there is the cat, which we meet again later!)

There is a painting by Velazquez focusing on just the triad (and a little monkey!) which is shown next to the Luncheon on the Grass in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The triad in Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass and in Velazquez’ Three Musicians (1618)

We return to this triad when we discuss the Luncheon in more detail.

Here, I want to point out that the triad can be understood in social theory as a basic social unit:

The first-person represents the subjective perspective of the focused individual, the second-person is the partner in a dialog acknowledging the mutual presence and communicating back to the first-person (and perhaps to others), and the third-person is a participant and/or observer depending on the nature of the interaction.

The sociologist Georg Simmel – mentioned before – was the first to analyse systematically the formal position of the “Third” and its different roles (e.g. as mediating referee or as dividing and dominating the others). He demonstrates that it is the triad which essentially constitutes the basic social unit, because it is the triadic relation in which we experience that a social interaction – like a dialogue – can happen without us as first-person!

There is an objective social reality in front of us which does not depend on our subjective view or any specific individual or viewer. Children learn this around the age of three years (Tomasello 2019).

In MyManet, we assume that Manet had at least an intuitive understanding of this social phenomenon.

That is why he chose three persons in the centre moving the fourth to the back. Moreover, Manet saw that this triad had to situate the activity of painting in a social context:

The First engages the viewer/painter, the Second establishes the social reality of the group in front of us, the Third acknowledges the wider institutional context, the society, or the “world” around the painting.

And Manet reflects in his painting on this reality in a distinctly modern way. He keeps a reflective distance putting this reality “on stage” where he can manipulate it as the painter-puppeteer.

We can understand now why Manet avoids the backfigure. Letting the viewer enter the “stage” as a backfigure would destroy this reflective distance and make it difficult to control the level and the kind of engagement between the First and the viewer.

The social and philosophical analysis of this social reality “on stage” is available only a generation after Manet.

But he experienced already the impact of modernity on his own life and his relations to others, and his literary friends (Baudelaire, Zola, Mallarmé) described it in their novels.

The “Other”

Another crucial element is the figure of the “other” (green) representing an outsider view.

The “other” is placed in parenthesis because it is a rather complex figure with many meanings in the literature, and often put into parenthesis in other texts.

Let us try to clarify its roles and meanings:

On a first level,

the “other” plays just a role within the painting. While the Second (blue) creates the social space by looking at other participants from within, the “other” confirms their social space from outside.

All three paintings by Velazquez show these figures. Especially in The Drinkers, we see the central group surrounded by onlookers. In The Little Cavaliers, the “other” is connecting the frontstage with the groups in the middle.

We could treat the “other” figure as a potential Second – like the figure in the back to the right in The Drinkers, who is communicating with the figure within the group and might be joining as the activity evolves.

Similarly, we could speak of the Second as being the “other” for the First and Third. Just consider how Manet – in Luncheon on the Grass – moves the Second to the right side of the painting looking onto the other two!

In a more general usage, the partners of a first-person in social interaction are often referred to as the “others”, no matter how close or distant the relationship.

In MyManet, I prefer to make a clear distinction between the members of a triad (or ingroup forming a social space) and outsiders.

In the case of The Drinkers, the onlooker to the right – presumably a beggar trying to get some coins or a drink – might even be a total stranger to the group. Again, Simmel has taught us to understand the special role of a “stranger”, especially in the context of modern urban life.

On this level, the “other” is characterized by a cultural role:

the individualism of modern urban life makes us partially “strangers” to each other. We must come back to this meaning of the “other”, when discussing Manet as a “painter of modern life”.

On another level,

the “other” is looking from outside of the picture frame, as it were. Discussing Caspar David Friedrich’s Romantic painting, we saw that the viewer might – in a way – enter the painting from the front to the point that the backfigure appears within the painting.

Similarly, a person with a different perspective – say, a critic or the “alter ego” of the painter – may enter the painting from the back and appear in the role of an onlooker.

The “classical case”, as I pointed out, is the person in the background of Velazquez’ Las Meninas!

On yet another level,

the concept of “other” has a background in social philosophy (Sartre, Levinas) or psychoanalysis (Lacan). In this case, we have to consider a “deep structure” of social reality – either in society or in the personality – which confronts the self as the “other” – as a stranger to itself – with effects of alienation.

Some art historians apply this level in their interpretation, but they reach beyond the realism guiding Manet in his paradigm of a puppet theatre. (We will see a “depth” in Manet’s realism when we discuss the role of the “uncanny” in a later post.) The concept of “other” assumed in MyManet looks at painting as a social activity, where the participants and “others” are taking roles either within or around the painting as an installation in an imagined setting. We will say more on “deep structures” discussing other views on Manet.

Again, we should distinguish the role of “accidental other” from the “other” in a special compositional role related to the outside.

In The Little Cavaliers and in The Drinkers, the onlookers (green) support social spaces and the wider setting within the painting. The role and the number of onlookers is determined by the theme of the painting; they help to create unity in the composition.

In Las Meninas, however, the “other” in the background clearly communicates also with the outside of the painting. As I suggested in the previous post, the figure in the door in the background is about to “leave the painting through the coulisse”. He is in a double role: playing a role in the scene and representing an alternative view or perspective on the entire scene, including the space in front of the painting or the audience in terms of the puppet theatre.

A special case, again, is the “unrepresented other”. As we will see later, in some of Manet’s paintings the “other” is not depicted within the painting – as in Luncheon on the Grass – but rather implied and deliberately hidden “behind the coulisse”. The “classical” case is certainly Olympia, a painting he is already working on at the same time.

The Absorbed

Finally, we find figures (yellow) in the paintings who focus on something other than a person within the painting or whose direction of gaze is undetermined. Following Fried, we could say that all persons not directly engaging with the viewer are “absorbed” within the painting. Absorption would be the normal case (with the exception of portraits, where the sitter is typically looking at the viewer/painter). In MyManet, we distinguish more roles within the painting, because Manet uses their gazes to engage with different roles inside and outside.

Again, it is meaningful to distinguish between absorbed persons and “accidentally” absorbed persons.

In some cases, rather isolated persons are part of the theme; in other cases, it might simply be difficult to determine who a person is attending to. But in The Drinkers, the absorbed guy (yellow) in the centre plays an essential role.

In Figure 3, we see two persons absorbed in a book or in their own thoughts. Especially in religious themes, say, a praying monk, it might be more adequate to treat this absorbed figure as a Third, since the figure is obviously “looking beyond the painting”, perhaps with closed eyes as in Figure 4.

Figure 3: On the Beach – Suzanne and Eugene Manet at Berck (1873)

Figure 4: Monk at Prayer (1865)

As indicated in Figure 1 above, the persons in the painting will take their places either in a social space defined by their gazes and gestures or in a wider setting. The picture frame or the “stage” will delimit what part of the implied environment is actually visible.

Beyond this visible environment, we have to imagine the setting or installation of the painting with actors engaged in the experience of the work of art.

In MyManet, we assume that the borders between the setting, the stage or frame, the environment, and the installation of the painting can be quite fluid – just like in the reality of a puppet theatre performance.

So far, we have identified 5 positions within the painting,

although the absorbed persons seem to depend on the specific theme and will be only “additional” elements in a more general scheme.

The next step is to take a closer look at the formal positions populating the environment of the painting.

So, meet you next week!