Manet is not known as a painter of great emotions.

At his time, Eugene Delacroix was famous for painting expressive, emotional scenes, usually, referring to a mythological or historical event.

In case of Manet, critics complain that the figures in his paintings are curiously lacking emotions. They are not only “arrested” in their motions but also in their emotions.

Manet presents his figures in a way that the viewer feels like interrupting ongoing activities.

But typically, it is not even evident what kind of activities are interrupted and how the activity will be resumed.

The gaze of Manet’s figures is often described as evasive and unfocused or blunt and distancing.

Yet, they are not without emotion and their faces vary quite clearly in their expression.

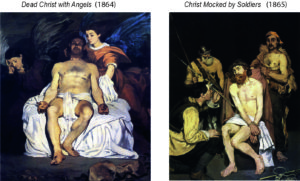

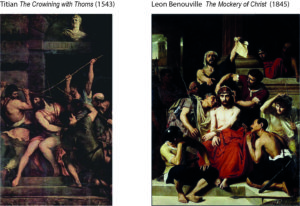

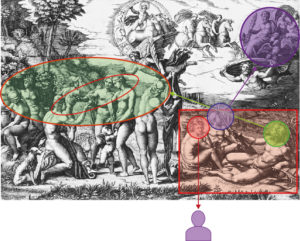

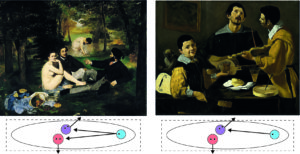

Figure 1: Four faces in Manet’s painting – four different expressions

In Figure 1, we see four faces – each one of the central figure in the painting (Luncheon, Christ Mocked, Olympia, and The Balcony) – and each with a very different expression. Two of the paintings we have already discussed, in case of Olympia and The Balcony we will take a closer look later.

Luncheon on the Grass, for instance, shows the woman recognizing the viewer somewhat sympathetically,

but we do not know what activity the couples are engaged in – presumably a picnic before or after bathing in the river – and what their relationships are – perhaps students having a good time in the park.

But then, the woman should not be naked in a public park…and the man next to her appears to be daydreaming rather than having fun.

How are we to interpret the somewhat reduced or detached expression of emotionality in Manet?

As stated previously, Manet does not want to tell Romantic or Historic “stories”. He considers himself a Realist and wants to show “what exists and what one sees” (Post 10).

And Manet wants do show contemporary life with the means of a painter and not with words, music, or dancing, or their combination in theatre and opera. His paintings are to show reality, but they do not talk or sing.

Strictly avoiding storytelling, Manet seems to except the consequence that he has to avoid emotions, too, since emotions characteristically arise in and are aroused by stories.

A painter cannot avoid telling stories without limiting the kind of emotions he can present in a painting.

In Impressionism we find emotional qualities reduced to general moods. In Expressionism, even Abstract Expressionism, emotionality is vibrant in paintings through colours, brushstrokes, and dynamic compositions,

but the scope of emotions is restricted compared to the subtleties of Symbolism.

I suggest that Manet’s choice can be understood better in view of recent theory of emotion.

He, obviously, was not acquainted with it, but he very well could have had an intuitive understanding of it, as we will see.

Jenefer Robinson in Deeper than Reason. Emotion and its Role in Literarture, Music, and Art (2005) offers a very readable discussion of recent theories of emotion and their application in the arts including painting.

Emotions are described as a very complex and multi-layered dimension of our experience and actions.

On a “deep” layer, emotions are reactions or physiological states which respond directly to states of the body or environmental impacts and their sensory perception (pain, hunger, thirst, fatigue, arousal, etc.).

Manet never painted pain, although he painted death – the ultimate arrest of motion and emotion.

On a behavioural level, basic emotions (Richard Lazarus) are integral parts of our coping behaviour;

they are based on affective appraisals of the person-environment-relation (e.g. pleasurable, threatening).

These appraisals are non-cognitive and may not reach our consciousness.

Manet does not show people in the process of coping with some problem or threat. Such scenes inevitably would involve dynamic “stories”. More often, we find his sitters on a sofa reading or in deep thought.

On the next level, emotions are “cognitively monitored” (Robinson). Integrating emotional feelings with cognitive evaluations allows for more differentiated ways of “being in the world”.

For instance, fright or fear, disgust, envy, guilt, shame, sadness, pride, anger relief, hope, compassion, love, jealousy, anxiety, and happiness have been identified as basic emotions integrated into our way of life.

Such basic emotions are common to all human beings; we experience our natural and social world through our emotions as well as through our cognitive faculties. Some of us are more skilled and creative in experimenting with emotions than others, but we all can “be” and “do” things, relating to our environment and expressing our emotions while pursuing cognitively our goals and values (except in certain pathological cases).

This is the level of emotionality many critics are missing in Manet’s paintings:

Emotions as conscious expression of subjective feelings or individual subjectivity, expressions of who we are as a person.

These emotions are further developed and differentiated by socio-cultural learning.

We learn which emotions are adequate in certain relations and situations and how to modify and express them (or not) in specific cases, and to recognize them and their variation in others. The emotions we express – or others express – are not necessarily mirroring the feelings we subjectively have.

But these emotions are public, they are meant to be understood by others.

This means that the emotions exist objectively for everybody to see.

The emotions can affect the emotions of others, including their subjective feelings.

In as much as situations define what actions persons can chose, they also influence what kind of emotions the actors will have or at least display.

Just like the fashion we wear, displayed emotions present in part who we are, although they may not be authentic and present only a certain side to others and to the public.

Manet was certainly much aware of the role of fashion and of the fact that Parisians – especially in his upper-middle class social circle – were very careful in displaying “appropriate” emotions.

“Appropriate emotions” correspond to the character or structure of a situation and depend on the respective position one occupies, the emotions will be objective.

Looking at the position a person occupies should tell us something about the emotions that person is likely to have and help us interpreting available emotional cues which typically are ambiguous.

Identifying the pattern of emotions is a capacity which we learn together with orienting us in a multi-person context where different actions are motivated by different goals and emotions.

More generally, we learn to frame situations as certain types with characteristic actions and emotions of participants:

“This is a situation I have experienced before and I did not like what a person in a certain role was doing to me!”

This learning process occurs in childhood and by learning by example from others – e.g. mother and father, sister and brother.

Cognitive and emotional aspects of experience and actions are in this process not separated but intimately related, both are embedded in our body and in our everyday life environment which we take for granted as we pursue our goals.

The process involves necessarily more than the child and its “environment”.

Focusing on the development of the subjective self, we (and much of psychology, including Robinson) tend to neglect that we learn emotions in a multi-person context where others play certain roles:

– To love somebody, there must be somebody to love.

– To be envious, one must experience that somebody (your brother; second person) gets something from somebody (your mother; third person) what you (first person) don’t get.

– To be competitive, one (first person) has to learn that an offer made by the other (second person) is only good if it is better than the alternative offer (by a third person) and that – if you are greedy and not trusted –

both may choose to exchange offers with somebody else entirely (fourth person).

Social relations and interactions are “charged” with emotions from the beginning before and while we learn to make finer cultural distinctions, tell stories about our emotional life to our friends or express emotions in the arts.

Social relations come in patterns; one person’s happiness may be somebody else’s misery.

Just like we learn (more or less skilfully) to locate ourselves in physical space and time allowing us to evaluate the accessibility of opportunities, and

just as we learn to claim and sustain our social position in relation to the position of others,

we learn to see our emotions as adequate feelings in view of the emotions of others.

Seeing the anger of the other because of the ruthless oppression by a third person, we find ourselves feeling sympathy for the underdog – unless we have learned to enjoy the exercise of power identifying with the oppressor.

Which brings us back to Manet.

Avoiding “great emotions” and storytelling in painting does not mean to avoid emotions altogether.

What we have to identify are “existing” dispositions and options for emotion in social relations,

which are, in a sense, “above” the subjective feelings and expressions embodied in each individual

and “below” the finer distinctions warranted by the “story” which a novelist might expound.

These are the emotions residing in the structure of the relations or which correspond to the way participants frame their activities.

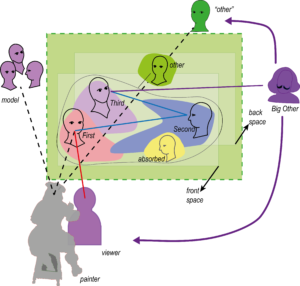

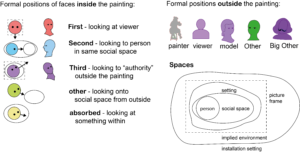

Back to Manet again, let us recall how he frames the situation of painting:

In My Manet, we assume that Manet shows a great interest in the social relations of painting.

These social relations reach beyond the figures in the picture space (“on stage”) and include the viewer, the painter, the model and other participants.

In discussing Manet’s realism, I also have proposed that Manet is aiming at “objectivity” rather than “subjectivity”. This means, he is interested not in showing how a person expresses his or her very personal emotional life

but rather what opportunities exist for certain emotional states given a certain position in social space.

In the analogy of the theatre, Manet is not showing the performance but the role in the script and the position of the actor on stage.

Relations in social space have a form and a content, they form a pattern and create opportunities for actions and emotions as content.

To visualize form and content in this structural sense, let us look at a simple social scene and represent its structure in diagrams:

Example:

Imagine a mother telling her somewhat reluctant son to bring out the garbage (certainly a realistic scene!).

Now she can say either of four things:

A: “O.K., if you bring out the garbage, then I will give you time for your gaming.”

(meaning: you give something I want, I give something you want

– an exchange of goods)

B: “Otherwise, when you don’t bring it out, then I will not allow you to go out tonight!”

(meaning: you do not something I want, then I see to it that you cannot do what you want

– an exercise of power)

C: (now pleading) “Look, we share the belief that in a nice family the children follow the wish of their parents. My wish is now that you bring out the (d…..) garbage.”

(meaning: you and I accept a norm, I invoke now the norm, and you should act accordingly)

– an interpretation or truth of a legitimate order)

D: (now exasperated) “I don’t want to offer you something each time I ask you to do something, and I don’t want to force you again and again, and surely I don’t want to have a big argument every time about why it is meaningful to follow the rules

– would you, please, do it just because you care for me?”

(meaning: you and I are members of a group or community caring for and trusting each other)

– an appeal to love and trust

We don’t know how the story goes on, but these are the basic options.

The mother can frame the issue either as a matter of exchange, power, truth, or trust.

The framework sets “the stage” for the basic content of the interaction.

Whenever one person wants that another person takes the next step in an interaction, these alternatives (or a combination) are “in the air”. They are the medium for creating motivations and, depending on the actions chosen, they determine the scope of appropriate emotions.

Daniel Coleman – in his bestseller Emotional Intelligence (1995, p.111-2) – describes a wonderful case where a 2 ½-year-old boy is already pulling all four registers in trying to calm down his 5-year-old brother.

We learn the basics of emotion in interaction already early in life!

The situation becomes more complicated when more than two persons are involved. The situation will also change as the interaction goes on and alternative actions are chosen by the participants, perhaps altering the frame.

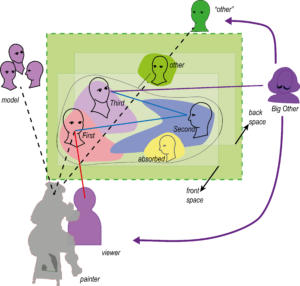

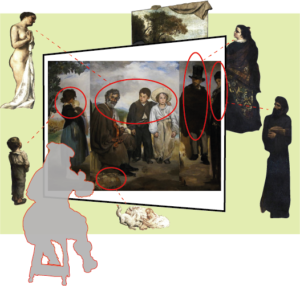

But as a first step – with Manet in mind – we can now draw simple diagrams involving only the self and the other as in Figure 2.

As a frame, we use the four options from the little scene above. In the centre we place the four faces and assign – tentatively – an emotion to each one.

The faces and frames are arranged in a fourfold table or a “field of four forces” since each corner wields its particular influence over all options.

Figure 2 : Four Faces and their Emotional Expression in Manet’s Paintings in the Structural Framework

Let me comment each face and its place in the framework, starting with the Luncheon on the Grass.

Luncheon on the Grass

The self is the central woman looking at the viewer, the other in this case.

Her gaze is mildly sympathetic and trusting. We assume a relation to the viewer which is characterized by some communality and symmetry indicated by the enclosing ellipse.

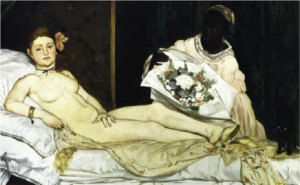

Olympia

The self is the courtesan looking at the viewer who finds himself potentially in the role of a customer.

Her gaze is somewhat distancing and self–asserting demonstrating that she is defending her high-ground. The relationship is clearly asymmetrical and “business” with no underlying communality (no circle).

The Balcony

The self is a woman sitting on her balcony, in public view, but she directs her attention not to the viewer but to some other person or to some event of interest to her in the street.

The relationship is unclear, perhaps the other shows also interest in her. The relationship is basically symmetrical – since the other seems not to exercise any power – but it is also not inclusive (no circle).

Christ Mocked by the Soldiers

The self is here Christ directing his gaze to God Father (Big Other) in awe and humility.

The relationship is obviously inclusive (circle) but also asymmetrical with God Father representing an inclusive entity exercising “authority” and representing a legitimate order or higher truth which, in this case, can even demand the sacrifice of Christ’s life.

Obviously, there is much more to say about the paintings and their figures including the other roles of Manet’s scheme.

And I will say more about the essential social categories – highlighted in italics – and represented in the little diagrams as we go along to other paintings.

The point is here that we can approach the question of emotions in paintings in different ways:

The usual approach focuses on the individuals and their expression of very individual feelings.

Their emotions might be triggered by events or “stories” depicted in the painting.

Or: In expressionistic paintings, the viewer might find himself or herself in the role of being emotionally affected by the painting.

Manet seems to prefer another approach.

He positions his figures in a network of formal relations, a social form, and provides only the necessary cues for interpreting the emotional dimension of the objective scene without digging into their very personal emotional life or imposing the emotions of a “drama” on the actors.

Manet does this in a Realistic manner in two ways:

– He opens the social space of the painting to include the viewer and others around the painting, since the reality is that the paintings gain their reality only by “being-seen”.

– He shows what exists and what one sees in the reality of the painting situation – typically in his atelier.

Here, Manet arranges his models “on a stage” which he indicates in his compositions and he shows the emotions his models really show in that situation. Sometimes, he makes a lot of effort to create an arrangement in his atelier which transports an outside “reality”, e.g. a bar, into his atelier. But his realism demands that this fact remains transparent to the viewer.

Manet does not follow a naturalistic approach trying to copy what he sees but shows what exists beyond the accidental appearance of the arrangement – a “reasoned imagination” (see Post 10).

Applied to emotions, this means showing the emotional dimension of figures, their positions and relations as they are displayed and publicly accessible in the situation – just like the fashion and cosmetics of a beautiful woman!

A final remark for today:

Manet does not show or express his own emotions.

Critics – especially, under the influence of Expressionism and Marx or Freud – have attempted to demonstrate how Manet was hiding his own emotions, but “betraying” (Robinson) these emotions in subtle ways in his paintings.

This may well be.

But in MyManet, we do not need to assume that Manet somehow suppressed his own emotionality.

His Realism motivated him to “show what exists and what one sees” when painting.

Manet was a “sincere painter” – as all who knew him confirmed.

Speaking of beautiful women, now that we have clarified how Manet treats emotions, we are prepared to look at the greatest scandal of his painterly career, the Olympia.

Sorry,

but I have to change my usual invitation “See you next Week!

I will enjoy a summer pause like everyone and everything in Finland.

So, See You in a month on August 12th!