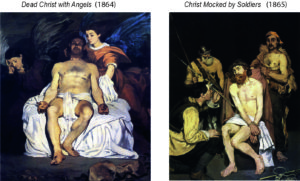

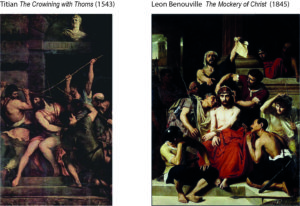

Both paintings of Christ – Christ Mocked by the Soldiers and Dead Christ with Angels – have been interpreted as hidden self-portraits.

A certain likeness exists, especially in Christ Mocked (see previous Post 14).

But I agree with James Rubin (2010) that the relation is more metaphorical:

Manet is presenting himself as a painter through the painting rather than representing himself as a person in the painting.

This prompts Rubin to draw a connection to the Self-Portrait with a Palette

(see Post 12).

Figure 1: Comparing Dead Christ with Angels(1864) and Self-Portrait with a Palette (1879)

Here, I like to cite Rubin (2010) at length:

“Additionally, Christ’s body is so intensified by its life size, frontal position, and proximity more blatant than in any art-historical precedent that as an image in reverse it could connote a literal mirror image of whoever contemplates it … imposing on the viewer’s actual space and forcing a response. “(p. 102-3; emphasis added)

“In his paintings of the 1860s, Manet responds not just to the eye but to the gaze; he represented not just the hand but its creative function; he imagined not only the appearance of the body but its vitality. The body, whether nude of clothed, was rarely neutral but rather powerfully present and communicating with the viewer’s realm as well as bearing the marks of the process of its creation.

The Dead Christ with Angels is the painting in which these characteristics are perhaps most compelling.

For here the marks of a corpse coming into being within art ironically suggest the opposite processes of decay and death….The drama of life and death, creative power and inanimate substance, is represented by the hand

– the hand of Christ as represented by the painter and, as in the self-portrait, by the painter’s hand painting itself.” (p.156; emphasis added)

Three themes are suggested by Rubin:

– Manet’s motivation to present himself in the image of Christ

– the meaning of the mirror

– the role of the eye and the hand in the representation of the painter and painting.

For all three themes Rubin offers an interpretation which goes beyond the limits of this post, and I recommend Rubin for deeper insights drawing on philosophy (Schopenhauer) and psychoanalysis (Lacan).

But I would like to add some comments in view of MyManet looking through the eyes of the painter in his aim to engage the viewer:

First, Manet does not imply a direct identification – the artist Manet as God-like – but Rubin points out that Dead Christ with Angels is an “optimistic work” (p.105). The artist, the viewer, and Christ’s realistic body are sharing a rather intimate space and a close relationship in the experienced presence meaning that there is a potential for transcending suffering and being creative not only as an artist.

Second, the mirror is an important means of self-reflection, not only in the process of painting a self-portrait, but also for the reflection of one’s identity and role in life.

The mirror is not shown directly in either painting; in Figure 2, I have added a yellow frame indicating the mirror. Rubin points out that the paintings create the impression of a close distance as taken in front of a mirror.

This is obvious in case of the self-portrait but also in both paintings of Christ.

In the case of Dead Christ, the wound of Christ from the spear (under his heart) is on the wrong side – as if reflected in a mirror. Critics at Manet’s time were quick to point out this “mistake”. Manet refused to correct this, apparently because the effect of a mirror was intended.

Figure 2: Christ embodying Manet’s scheme and Study to Dead Christ with Angels (1864)

In fact, in the study (Figure2), the image is not mirrored and the wound on the “correct” side.

Since the study is not a print (where we might expect a reversed image) but in oil, Manet is experimenting again.

Another clue for the existence of a mirror is not mentioned by Rubin.

Looking closely at the toes of Christ’s foot extending toward the front, we see a strange diffuse spot reminding of the painting hand in the self-portrait (Figure 1).

The toe seems to be touching the mirror! (yellow circle in Figure 2)

In the study this detail is not indicated and the foot is not extended so far forward.

Thus, Manet made the change deliberately.

The self-reflective gaze into the mirror draws the viewer (and the painter) into the space of the painting.

At the same time, by making explicit the role of the painting as a mirror image beyond the picture plane, the painter/viewer can distance himself or herself from the image and take a fresh and objective look.

In the case of the self-portrait, we saw that the painting initiated and mediated a communication between the painter, his image and the viewer by having the painter “seeing you”. In case of Dead Christ, both painter and viewer are asked to reflect on themselves as if “seen as Christ”.

Moreover, a special effect of Dead Christ resides in the fact that Christ is not looking at the painter/viewer but presumably to God Father – though with an inward or “absorbed” gaze. The mirror supports an expectation of Christ “looking at you”, while Christ’s gaze redirects your gaze to God or the “Big Other”.

In the study (Figure 2), Christ is looking more toward the viewer establishing a direct contact in the role of the First. In the finished painting, Manet redirects the viewer’s gaze toward the body and the hands, and directs Christ’s gaze away from the viewer.

Third, the redirection of the viewer’s gaze creates a very complex situation which leads us back to Manet’s scheme. Christ looking at God Father places him into the role of the Third looking outward. The two angels are “absorbed” in mourning (yellow); perhaps the one holding Christ from the back may be seen as doubling in the role of the “Other” (light green). I prefer interpreting the angels as creating the mourning atmosphere or a “coulisse” (this effect is stronger in the study) while Christ is presented “on stage” (light middle ground).

In the case of the self-portrait, I suggested that the self in the mirror may be seen in either of the four roles of the scheme.

In the case of Christ, we might see him incorporating all four roles:

The illumination on the “stage” creates a strange depth in the painting:

The foot reaches forward into the darker frontstage (enhanced in red), while the head recedes into the darker backstage (green triangle).

The gaze of Christ is directed inward/outward relating to the external “authority” or the “Big Other” (purple circle).

For the roles of the First and the Second, we return to Rubin’s interpretation relating the painter’s eye and hand. Eyes or gazes and hands or gestures constitute for Manet the space of painting.

In the self-portrait, the eye is “seeing” and representing reality, the hand is “performing” and presenting the reality as seen by the painter.

Christ is not looking at the viewer (or painter) but reaches out with his foot which bears the mark of a wound like an eye. Similarly, the two hands are opened and presented to us with their wounds like eyes.

Christ is “facing” us with his wounds.

The “eye” on his foot takes the role of the First (red circle), the “eyes” on his hands mediate in the middle ground taking the role of the Second (blue circles) and preserving the unity of Christ’s vulnerable body.

We have seen this unifying role already in the Luncheon on the Grass, where the hand of the Second – the person to the right – is placed in the centre of the triad with an inclusive gesture.

Finally, compared with the study, Manet places Christ’s head further back into the dark and moves the head of the caring angel into the light. This supports a double role of Christ:

– as the Third, he directs his dying gaze toward God Father;

– as the “Other”, he is looking from the dark background increasing his distance from the viewer who is focusing on the illuminated dead or dying body.

We need not agree on one or the other interpretation. Clearly, Manet is creating an ambiguous space, as Rubin characterizes it, with a dynamic of intimate approach and mourning retreat, of an optimistic view of life and a process of decay and death – “the drama of life and death”(Rubin).

The point is:

While Manet’s scheme is not immediately guiding the composition, as in Christ Mocked, we still can sense its influence in the way the dynamics of eye and hand, of gazes and gestures unfold in the painting and engage the viewer into an intimate social space.

Although the “drama of life and death” is the theme, Manet does not draw us into a dramatic narrative.

Again, Manet is presenting a “moment in between” and not telling a “story”.

Still, the two paintings of Christ are loaded with emotion compared with the other paintings we have considered so far.

But, typical for Manet, the emotions appear to “arrested” like the activities.

How does this fit into his formal scheme?

See you next week!