After Manet spend about six months in a clinic being subjected to a therapy which he experienced as an “atrocious torture” he painted an intriguing little Interior of a Café (Richardson 1982, p.112). The scene Interior of a Café follows several earlier works which Manet sketched and painted in 1878/79

– but it is strikingly different!

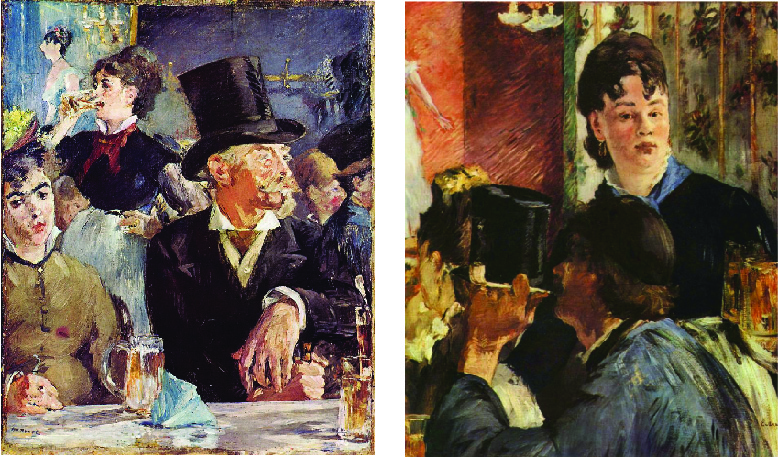

Figure 1: Three scenes in a café by Edouard Manet

(A) Café-Concert (1878) (B) The Waitress (1879)

(C) Interior of a Café (1880-1)

While in the earlier paintings – like Café-Concert or The Waitress – Manet appears to be close and sympathetically “rubbing shoulders with his subjects” (Rubin 2010, p.206), the Interior is more detached, and the place exudes isolation, loneliness and absence. The empty chair to the right bears Manet’s signature – certainly not a coincidence. And to the left, there is a strange, ghostly figure sitting at the table.

The art historians Richardson and Rubin do not comment on this difference to earlier scenes; they interpret the painting as another example of Manet’s engagement in modern life in Paris’ cafés. Both authors note, however, that a large mirror in the background seems to anticipate the mirror in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

As discussed in the previous posts, the Bar may be interpreted as a personal retrospective on his works. The Interior appears to sketch out some first ideas about his last masterpiece. If this is the case, we are encouraged to have a closer look at the Interior in view of Manet’s scheme as discovered in the Bar in the previous posts. Once we “see” not only a loose sketch of people in a café, we “see” Manet exploring elements of his scheme, looking back, and preparing the Bar.

Some puzzling elements in the Interior ask for an explanation. For instance:

- Why is the chair empty, or, who should we expect to sit there? Manet himself?

- The lady in the foreground seems to be looking at the gentleman at her table to the left. But is she? Her gaze is somewhat empty, not the least, because this figure is almost a “ghost” – faceless, only indicated in blue-grey, and cut off by the frame.

- What is role of this “ghost” in the painting? Is he looking at her or rather following the gazes of the other men to the right presumably looking toward the stage?

- Where is the waiter looking? Into the right side of the mirror or toward the stage? Is there a mirror?

Mysterious “absence” (empty chair), “darkness” (man at the table), and confusing mirror images (gaze of waiter) trouble the viewer when taking a closer look. Is this a scene which Manet was observing in a café or are we confronted with a puzzle or composition playing with absent pieces?

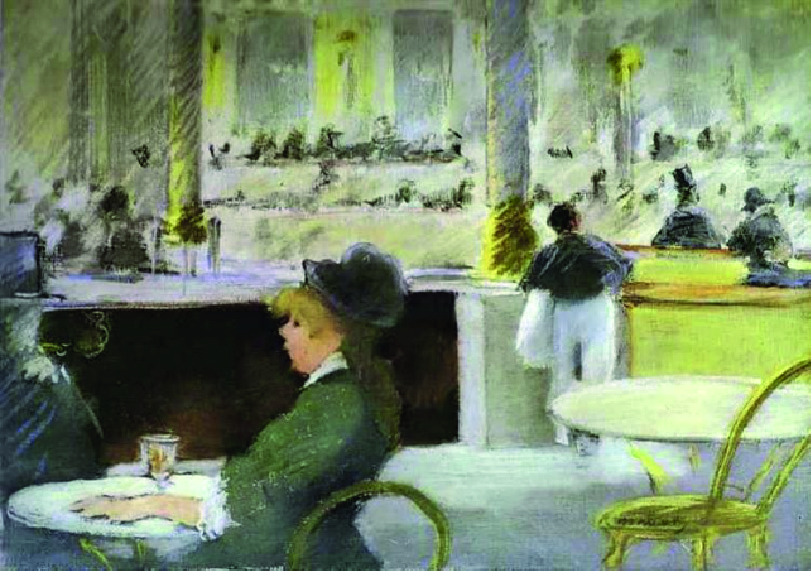

First, let us take up the question of the mirror (Figure 1C above).

The mirror in the middle ground – divided by a column to the right of the centre with a waiter standing next to it – is somewhat strange. It closes off the café in the middle ground and, at the same time, opens up a view to a large room “beyond the mirror”– actually behind the viewer – with what appears to be rows of visitors or an audience in a far background. Mirrors were (and still are) a common feature in cafés and appear also in earlier paintings by Manet and others (e.g. Degas and Caillebotte). Still, the connection with the reflection in the Bar – painted a year later – is suggestive.

On the left side of the column,

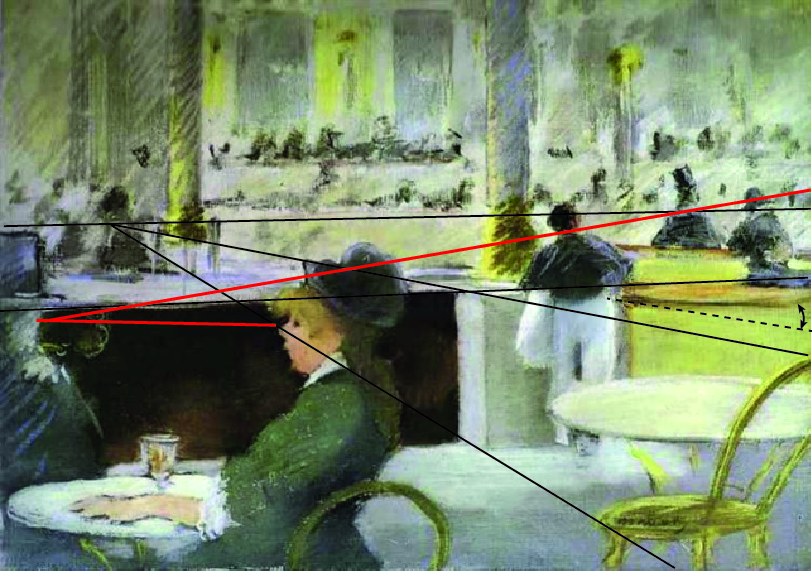

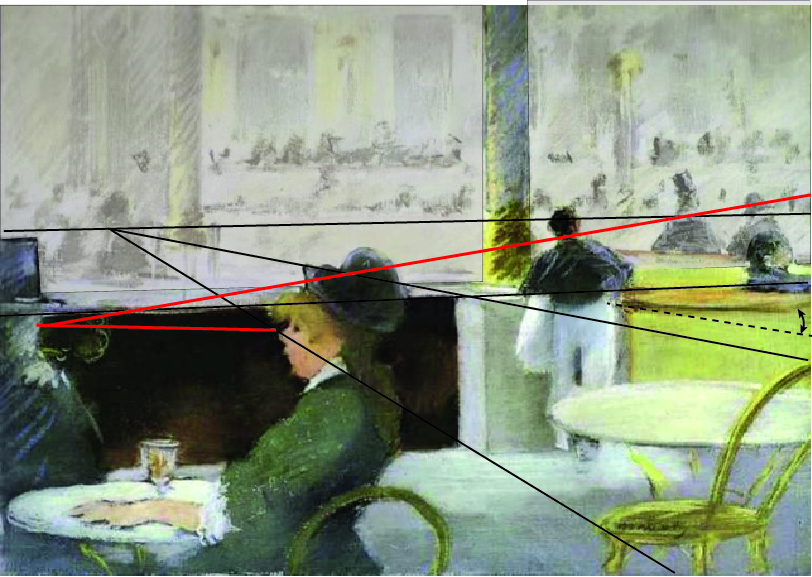

the mirror shows us the background behind the viewer standing apparently quite close to the woman and looking down on her. Like the gentleman at the table, the viewer would be placed toward the left edge and is not anymore reflected in the mirror, because the wall is not quite aligned with the picture plane. This creates a vanishing point far out to the right behind the stage and pulls the gaze of the viewer in that direction (black lines in Figure 2A).

Figure 2A.: Perspectives in the Interior of a Café

The mirror seems to reflect the woman at the table supporting the impression of a mirror and suggesting a perspective in the interior as indicated in Figure 2A above. The mirror also shows an open space above the woman, presumably the open space in front of the stage on the right. But the reflection is strangely empty, almost an “abyss” (like in the Bar to the left of the barmaid and similarly indicating people at tables or on a balcony beyond).

Strangely, the person in front of the mirror on a bench (to the right of the column at the edge of the painting) is not reflected in the mirror to the left of the column.

On the right side of the column,

the waiter and three sitting people appear to be looking at the event on stage beyond the frame. But where exactly are they sitting?

The wall with a dark panel beneath the mirror on the left side does not continue on the right side. Instead, there are the rear benches with those people facing the stage. But the rear bench is not aligned with the perspective of the room as mirrored on the left side.

In fact, the shading underneath the empty table suggests that the bench continues almost aligned with the wall (the angle in which the bench “should” go is indicated by the dotted line and arrow in Figure 2A above).

This has the effect:

If we focus on the right side of the painting, we don’t seem to see a mirror at all! The three people in the audience to the right are not reflected.

This again makes sense, since the gaze of the waiter is now unobstructed by any mirror and directed to the stage.

But then the mirror on the left side is deceiving – or there is no mirror to the left either.

Manet is playing games with the perspectives and with the viewer by suggesting a mirror on the left side and an open view to the space in front of the stage on the right side.

Let us look at the problem of the mirror with the help of diagrams, keeping in mind that we don’t know what the actual situation in this café really was and what liberties Manet took in representing the scene.

Our aim will be to learn something about the painting that helps us to understand its mediating role between previous café scenes and the Bar.

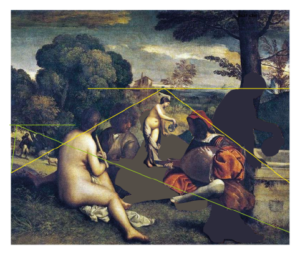

In Figure 2A above, we focus on the left side where the mirror reflects the woman identified by a greenish spot (her dress) and a black spot (her hat). Connecting the two faces we get a sense of the perspective (black lines) taking as a further lead the two columns and the white table the waiter is leaning on.

Manet seems to place a vanishing point behind the face of the woman in the mirror locating the empty chair in the “spotlight” of her gaze from the mirror. The chair is turned toward her and seems to be “looking back”.

The horizontal line gives further structure by connecting to the head of the waiter and of another gentleman on the far right.

An additional dynamic of the composition – indicated by red lines – leads the viewer’s gaze to follow the gaze of the woman to the ghostly face on the left and then to the gaze of the waiter picking up the general direction of the gazes of the three patrons on the right toward the stage.

We cannot be sure where the faceless “ghost” is looking. His gaze may be directed at the woman, instead, but the viewer is clearly induced to move his or her gaze along this trajectory.

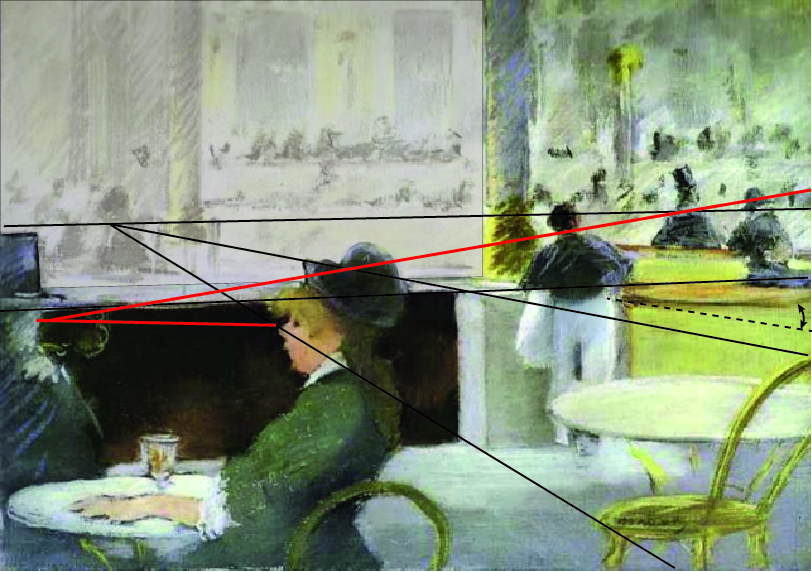

Figure 2B: Dimming the left mirror in the Interior

In Figure 2B, I have dimmed the left mirror. Now the view on the right becomes ambiguous as pointed out above. The gaze of the waiter, the large figure with the top hat, the backside of the benches, all seem to indicate that we look directly into an open space in front of the stage – not into a mirror continuing from the one on the left. But this would be incongruous with the image in the left mirror and the indication of a row of visitors running across the background of the painting.

Figure 2C: Dimming mirrors on both sides of the column in the Interior

In Figure 2C, I have tried to amplify this point by dimming also the right mirror. Now it becomes apparent that the patron on the far right would be sitting this side of the mirror while the other two are reflections.

The problem is that the person on this side is not reflected in the mirror. Moreover, he is cramped into a tight space next to the mirror because the bench does not follow the perspective; the angle (arrow) is too small. Additionally, the white light beneath the table pushes the yellow bench clearly to the back, more aligned with the dark panel on the left.

All this supports the dynamics of the red trajectory, but it makes the mirror images and perspectives of the café inconsistent.

Figure 2D: The “real” scene in the Interior (with dimmed mirrors)

In Figure 2D, keeping the dimmed mirrors, we see (with the help of some rough photoshopping) what the situation “really” might have been.

Now the bench follows the perspective, the patron to the right has some space and is reflected in the left mirror as a shade above the women’s head. Underneath the table we see the bench angling out into the room.

But this “reality” comes with a cost. The right mirror is closing off the background to the right more effectively, blocking the gaze of the waiter on the other men. His gaze loses some of its force, since the gaze of the “ghost” is now more likely to follow the gaze of the patron to the right towards the stage on this side (red line). And perhaps most importantly, the table with the empty chair loses much of its dominant position, cramped up next to the bench.

So, it seems that Manet knew what he was doing when he created an ambiguous right side, neglected the laws of perspective, put the empty chair in a “spotlight”, and supported a dynamic trajectory in the composition toward a stage somewhat “beyond the mirror”.

The point here is not to demonstrate that Manet manipulates perspective to create a compositional effect; we saw this in other paintings.

The point is that these elements – mirrors playing with perspectives and with gazes of persons including the viewer, introducing “ghostly” figures, leaving and “abyss” in front of a stage beyond the picture frame – resurface in the A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. This makes the little Interior a work mediating between the previous café paintings focusing on modern life and his final masterpiece reflecting on his work in a multi-layered composition.

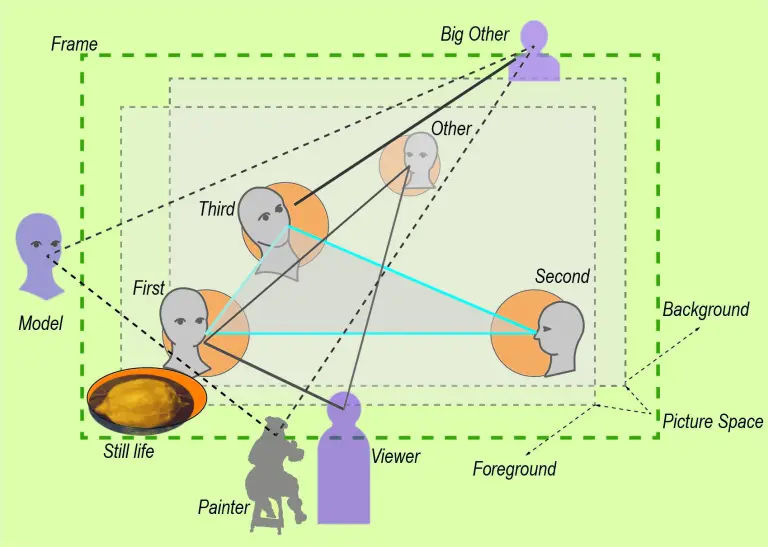

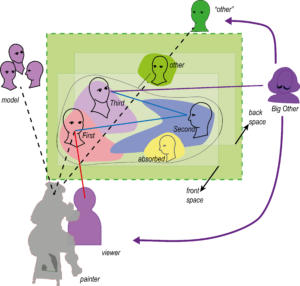

This means, moreover, that it is meaningful to apply Manet’s scheme to the Interior, and to identify the triad of persons (First, Second, Third), the Other, and the Big Other beyond the picture space (see Post 26).

Obviously, the First, looking at and engaging the viewer is missing – there is an empty chair!

Considering that Manet typically engages the viewer, like in “The Waitress” in Figure 1 above, this is surprising and invites the interpretation that Manet sees himself “missing” and missing “looking at the viewer” in painting. After the stay in the clinic, he realizes that soon he will not be able to enjoy the bars and cafés with his friends anymore.

The Second, the person looking across the picture space and establishing the social space, is clearly the woman in the foreground. But – unlike the man on the right in the triad in Luncheon on the Grass gesturing to the other two – she has only a ghostlike figure sitting at her table.

She is turning her back to the empty chair, isolating it further by her own position left of the centre . Her connection with the missing First is only indirectly by way of her mirror image located at the source of the “spotlight” on the empty chair.

Her unfocused facial expression only motivates the viewer to follow her gaze to the “ghost” and to the waiter’s gaze who seems to be attracted by the event on stage.

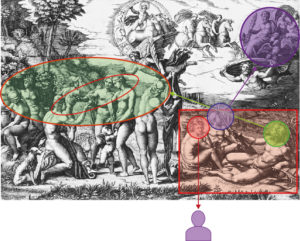

Even more puzzling is the role of the Third, the person directing his gaze beyond the picture space toward the Big Other, the external “authority” in Manet’s scheme.

In effect, the “ghost” and the waiter share this position creating the red trajectory across the painting toward the stage beyond.

But this trajectory is unstable, as we have seen above. The origin of the Third’s gaze in a faceless “ghost” makes us wonder if Manet is not only missing his life as a painter engaging with the viewer, but also missing the “authority” of painting which he always saw in the tradition of art. The gaze of the Third is now directed toward a stage which exists in an insecure space of conflicting mirror reflections.

Finally, the position of the Other, looking from the back at the triad, is taken by the mirror image of the woman. This element we find, in almost the same position, in the Bar (Post 26). This supports the interpretation of the Interior as an experiment with ideas for the Bar.

Returning to the questions above, we see how “absence” dramatically enters his work. It has been characteristic of his paintings by the openness of his compositions reaching beyond the picture space toward the viewer and other implied presences. It often found expression in the absent gaze of protagonists in his paintings. But now under the impact of deteriorating health the place from which he establishes the contact to his viewers – the gaze of the First – is empty.

After the Prussian-French War (1970-71) we can observe how Manet experiments with fewer actors in his scheme. We will return to these works in following posts. But now he is almost dissolving his characters in “missing” and “ghostly” figures turning away from each other in an ambiguous space. I find this little Interior somewhat depressing and expressing his deep sadness, while his final masterpiece – aimed to establish his position in the tradition of art – demonstrates his self-confidence as an artist.

The ”ghostly” greyish figure and the imposing dark area behind the figures at the table remind us of another aspect in Manet’s work, the “dark” and “mysterious” elements which seem to emerge from a “dark backstage” (see Post 28). We will turn to the “Dark” in Manet’s painting in the following post.

See you soon again!