Manet’s Breakfast in the Atelier is still fascinating me – and I got hold of another source with new insights.

So, The Balcony – which I planned for today – must wait until next time.

In the previous post on the “Enigma” of Breakfast, I distinguished between a content level and a design level. There are, obviously, many more levels of interpretation.

To acknowledge the complexity of this painting, I should complement the view of MyManet with additional levels or layers of meaning.

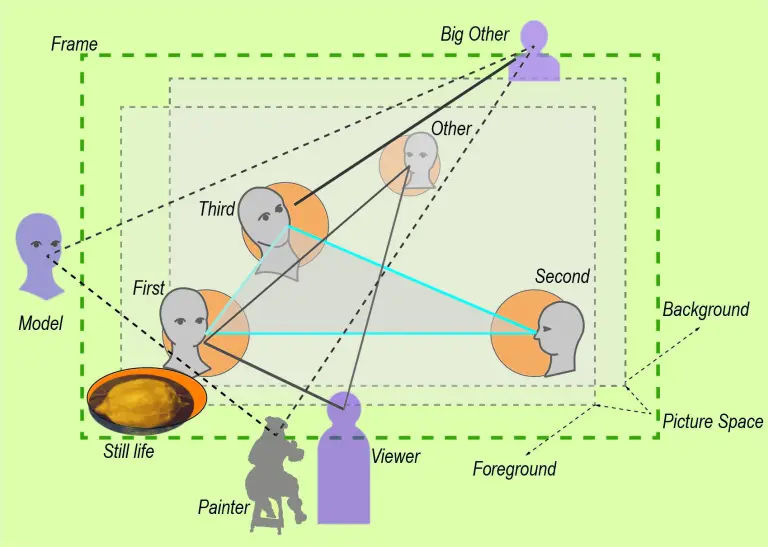

Figure 1: The viewer’s gaze moving over the Breakfast in the Atelier (1868)

Some layers are more connected to the design of the painting – the order of elements.

In Figure 1, I tried to indicate how Manet is directing the viewer’s gaze over the picture space – at least my gaze.

The gaze of other viewers may roam differently, but I think my reaction is not totally missing what Manet intended.

I return to Figure 1 shortly.

Some layers are created by the content associated with the figures and requisites shown.

Presumably, there are “hidden” meanings “betrayed” by what is depicted, such as an allegory of painting or an underlying “family drama”.

Let us return to Figure 1 and look at the design:

The painting is troubling for the viewer showing a lot of figures and things which seem to be quite arbitrarily assembled.

But there is some order – not the least by the way the viewer will try to “read” the painting (and Manet will lead the viewing):

Obviously, the boy on frontstage is capturing the viewer’s gaze first.

However, the boy is ignoring the viewer. This is not very polite and, additionally, he is almost stepping out of the painting violating the personal space of the viewer.

So, we might step back, and – in a second attempt – turn to the maid in the background.

After all, she is looking at us returning our gaze. We are invited to come closer again, but there still is that boy with that dominating black jacket. Avoiding his presence, we might step back again and look to the right to the brightly illuminated table with the breakfast. Instinctively, we step closer, since the lemon is almost dropping from the table – we have to catch it!

This way, we approach the man looking to the left side of the painting.

So, stepping back again – and easing our way around the boy – we look also to the left side.

Here the white flowerpot with its – somewhat “out of place” Japanese decoration – catches our attention. It is way in the background, but we don’t step closer because it is somehow looming large (“facing” us) keeping us at bay.

Trying to bridge the void in the middle ground, we focus on the still life on frontstage, and we are amazed and puzzled by this theatrical arrangement ad odds with the Japanese flowerpot.

Are we in an atelier or at a breakfast table?

Then, we discover the black cat – and we realize we are looking at a painting by Manet, the painter with the black cat!

O.K., now we know that this must be an allegory of Manet reflecting on painting.

Knowing that he loves citing painting traditions and his own works, we start the “treasure hunt” of the art historian, and we will find a lot of elements referring back to other paintings.

One of the observations I like very much is offered by Richardson (1982):

Behind the back of the boy, there is a diagonal connecting the Dutch looking maid and the still life in the Dutch tradition on the table (also citing an own painting). There is another diagonal leading from the romantic smoker (Richardson) to the assemble of theatrical requisites on the front left (again citing own still lives and the puppet theatre).

Richardson also points out that this retrospective painting is produced when Manet recovered from a period of “self-doubt and gloom” (p. 17). This explains the self-reflection in the painting.

Our view of the painting moved from a first, somewhat disoriented, impression of complexity (level 1) to reading more and more order into it – following the way our gaze is directed (level 2) – and, then, associating the meaning of elements with Manet’s work (level 3).

We also experienced – if you followed my experience – that not only roamed our eyes over the picture space. The eye movements even induced a “dance” stepping back and forth and sideways trying to engage with different elements.

A great example for how Manet is engaging the viewer!

On yet another level, the view of MyManet suggests seeing the painting as a variation on Manet’s scheme. This was the theme of the previous Post 18.

This level, I like to enrich with two insights gained from my new source, “moments of thought” which Werner Hofmann (1985) devoted to Breakfast in the Atelier.

First, Hofmann shows an x-ray of the painting which indicates some interesting changes made after the first draft.

Most commentators point out that the scene originally played out at his summer resort at the sea in an atelier with large windows in the background. Returned from the resort, Manet closed this background with a wall and with a painting (to the right) creating a more domestic ambience. This domestic flair is further supported by introducing the maid in the final version who may be serving some milk (in a can bearing the letter “M”).

More important in view of MyManet, with her, the role and position of the First looking at the viewer is entering the painting. Back home in Paris, we might say, he re-conceived the painting in terms of his scheme!

Another important change occurs to the smoker to the right.

In the draft, he is looking more at the back of the boy (and along the diagonal toward the weapon still life). Now his hand is moved somewhat between him and the boy and his gaze is directed across the middle ground to the left.

With the introduction of the First, the maid, in the background, and with the Third, the boy in the foreground, Manet now covers the middle ground with the gaze of the Second, the smoker.

These changes enhance the “dance” of figures over the “stage” and make the viewer “dance” in response!

Second, another observation by Hofmann concerns the gaze of the boy.

This insight, I like to relate to the interpretation of Nancy Locke (2001). She chooses a psychological reading of the painting starting with the fact that Leon is the illegitimate son of Manet (or of Manet’s father?). According to her, there is a “tone of estrangement” (p.131) in the painting. This estrangement gains momentum when we identify the man to the right with Manet himself and the maid with the mother, Suzanne, a Dutch woman! Then the boy will turn his back to a situation of illegitimate childhood and look into a yet indeterminate future adulthood.

This is certainly an own and important layer in the interpretation. She adds another layer by pointing out that Manet had himself a very problematic relationship to his father. Only after his father’s death in 1862, Manet – somehow liberated – had his breakthrough in painting. In this view, we might even see Manet’s parents looming behind the vision of Manet and Suzanne as suggested on the previous layer.

Locke is exploiting here the theme of the father-son relationship and its psychoanalytic significance.

And Locke takes still another turn with the theme of father-son relations. She connects the Breakfast with Manet’s religious paintings. According to her, Manet’s paintings of Christ are variations on his relation to his father: “Manet paints a gaze that expresses the difficulty of accepting the will of the Father” (p. 139).

In view of MyManet, this is a very interesting way of interpreting the gaze of the Third!

We suggested a similar interpretation for the gaze of Christ – the role of the Third – in Christ Mocked by Soldiers (see Post 14).

Locke proposes a psychological interpretation of the Third. She somewhat abruptly changes between paintings – from Breakfast to Christ Mocked, from Leon as Third looking at his “father” to Christ as Third looking at his “Father”. Leon is not looking at his “father” at the breakfast table, unless we follow the interpretation of Gisela Hopp (1968). She sees the boy daydreaming and imagining the very scene pictured behind him.

So, the connection is the more general theme of the internal conflicts of a father-son relation and the role of the “father” as an internalized authority.

Figure2: From “looking out” to “looking without seeing”

– Manet’s portraits of Leon and the “iconic barmaid”

![]()

Hofmann offers an interpretation which is less psychological and more rooted in the tradition of religious painting.

With the loss of religious convictions, the gaze toward a meaningful agent beyond all sensory experiences loses its “transcendental axis” (p.79). The gaze of “looking without seeing” does not express security in faith anymore but alienation and individual isolation. Hofmann sketches this development since the 15th century with some fascinating examples. With the loss of the (religious) narrative, the figures become “icons” of the human condition in modern society.

In Figure 2, we can see how Manet in his own work changes the view on Leon from the child posing in a “Spanish” painting to the realistic view of him in the drawing. Then – in Breakfast – we see the “turn to the icon” (Hofmann). The boy is not just depicted like we “see” him but shown as an “icon” representing how it is to “exist” in the situation of a boy on the threshold to adulthood.

To highlight his point, I have added the famous “icon” of Manet’s “looking without seeing” – the barmaid in his A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882).

In view of MyManet, I like this interpretation of Manet’s figures as “icons” of the human condition. It is a meaningful way of capturing Manet’s scheme as a “social form” assigning roles and positions. The Third “looking without seeing” is not focusing attention on “what one sees” but experiencing “what exists” (see Post 10 on Manet’s realism). Following Locke (and Sigmund Freud), we can agree that the realities of psychological conflicts in family relations are also exactly that: existing realities.

However, we have to come back in a later post to the social dimension of the scheme.

For Manet, the human condition was not so clearly characterized by individualism and isolation as Hofmann and later expressionistic and existentialist visions of modernity would see it.

Manet still believed in tradition and institutions – submitting his paintings to the official Salon – and he infused his figures with the energy of a social existence and awareness (see previous post) that united them beyond their individual subjectivity.

Last comment: With all those reflections on the father-son relation, we seem to have lost the female perspective. In Breakfast, the female plays only an “assistive” role (Hofmann) in the background and is painted rather undefined.

That changes clearly in the next painting! In The Balcony, females are frontstage.

See you in two weeks!

Leave a Reply