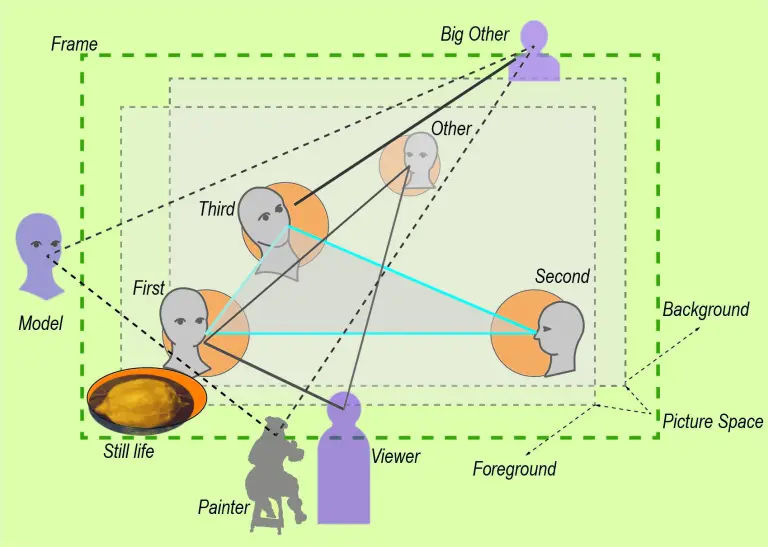

In the previous posts, I have developed a scheme which – as proposed by MyManet – is guiding Manet’s composition of Luncheon on the Grass. The claim is that this scheme is not only a scheme for this painting but is a “hidden scheme” informing also the composition of following paintings.

To show this, I first want to apply the scheme to his self-portraits.

Manet painted only two self-portraits late in his career 1878-9. He inserted small images of himself in early paintings like The Fishing and Music in the Tuileries, as we have seen, and later in Masked Ball at the Opera. But they were not self-portraits in the narrower sense, more like ironic comments.

It seems that he did not especially like to paint self-portraits, although he liked his painter friends, for instance, Henri Fantin-Latour and Edgar Degas to picture him. Figure 1 shows two often reproduced pictures.

Figure 1: Portraits of Manet by Henri Fantin-Latour and Edgar Degas

The pictures and the self-portraits below show Manet as the “dandy” enjoying his life as a painter. And most references to the paintings just use them for illustrating this point. But there is more to them.

So, one question concerns the Why?

Why did Manet paint self-portraits rather late in his life?

An interesting remark by James Rubin (2010, p.372) suggests that “Manet’s self-portraits certainly look back to the dialogue of gazes in his pictures of Victorine and Morisot” (e.g. Luncheon on the Grass and The Balcony – RP).

Rubin does not elaborate this remark and goes on to suggest that they also “set the stage for A Bar at the Folies-Bergére”, the last great masterpiece by Manet.

This seems to imply that the self-portraits demonstrate in some way the scheme of MyManet, and that the scheme, in fact, never loses its relevance in Manet’s painting over the stages of his career.

But, obviously, a self-portrait is not the kind of painting to which we would expect the multi-person scheme to apply.

On the other hand, if I can show that the scheme helps to interpret Manet’s view of himself, that would be a great test for the scheme.

So, let us try!

Figure 2 shows the two self-portraits by Manet and below a detail from Las Meninas by Velasquez with the master himself, and a painting by the very young Rembrandt standing somewhat lost in his bare atelier. Velazquez we have met in earlier posts as Manet’s idol. The little painting by Rembrandt I found in An Introduction to Art by Charles Harrison (2009).

Figure 2: Manet’s Self-Portraits and Self-Portraits of Diego Velazquez and Rembrandt

Self-portraits typically show what Lüthy (2006) has described as “seeing oneself seeing”, the painter looks at himself or herself in the mirror (or in a photograph) and sees the image looking back.

This reflexivity is a welcome starting point for philosophical interpretations which the painter may or may not have entertained himself or herself.

I want to set these interpretations aside and rather take the view of MyManet. In this view, Manet is foremost a realist and attempts in all sincerity to “show what exists and what one sees” (see Post 10). This includes for him to place the activity of painting into a setting which implies a social space and an environment (e.g. his atelier) with actual (e.g. the model) or virtual (e.g. the viewer) others.

In this scheme, the figure in the self-portrait can be seen in different roles:

Case 1: The figure is the First looking and engaging the viewer and/or painter.

Most self-portraits, not only Manet’s, chose this role. The painter is presented as a person ready to communicate with the viewer, even when the figure is shown in different emotional states and signalling the incapacity or unwillingness to engage with the viewer and rather addresses himself or herself. In these cases, the painting demonstrates even more the reflexive engagement with the painter.

Case 2: The figure is the Second, typically alone in the painting and looking outside the frame, although only to present the (half-)profile to the viewer.

The objects in view of this figure are irrelevant to the painting, of relevance may be the very fact that the painter does not show his frontal face. This creates a distance from the viewer which can signal, for instance, a social distance of a person of status.

Manet’s self-portrait standing in his atelier may be seen as a version of this case.

In fact, I think that this self-portrait is made exactly to experiment with this case, while the self-portrait with palette experiments with the other cases. Both paintings are created at the same time.

He can be interpreted to look critically at the painting itself rather than at the viewer, quasi looking from the side. The figure in the mirror (Manet) will be standing to the left of the painting and may even have a (virtual) view of the painting. This is suggested by Barbara Wittmann, although she sees the gaze of Manet both as “absent” and “intensely” observing, which appears to me incompatible and stretching the interpretation (2004, p.223).

I agree that a painter choosing to present himself as not looking at the viewer does present himself as an “Other” (p.220), but only in the general sense of being “objectively” represented. Thus, Manet shows himself in the role of the model, and the model in the mirror substitutes, as it were, as a kind of double for the unrepresented Second. The viewer, not being the centre of the figure’s gaze, might imagine that there is somebody else just outside the painting. This would be a normal reaction when looking at someone who is not looking at you.

This case 2 raises the interesting problem that Manet as the painter cannot see himself with the gaze of a Second

(or an absorbed figure) – the figure not looking back at him – in the mirror!

Nobody can – again, a great starting point for philosophical interpretations.

In the age of photography, already at Manet’s time, we can look at our image in profile or as absorbed gazing at some other object. Or we might have a friend like Degas who can draw us (see Figure 1). But we cannot see it in the mirror.

For a naturalistic realism, this is a problem because one cannot see and paint what one knows to exist – one’s view in profile – because one cannot see it. The realist Gustave Courbet famously said that he would paint an angel but only if he could see it. Well, he painted his self-portraits – like the image in The Painter’s Studio (Post 6) and many other self-portraits – without ever seeing it exactly that way. Following the tradition, he corrected the reversion by the mirror – showing the “real” Courbet he could not see – sometimes on the basis of a photograph.

For Manet’s realism, this is not necessarily a crucial problem. It is a fact of everyday life that we do not see e.g. all sides of an object and that we have to infer the “hidden” views which show what exists.

In his self-portrait with the palette, he must deliberately have chosen to paint the mirrored image – showing what he sees! Why?

In the self-portrait standing he also shows the mirrored image. But he shows a face that he cannot have seen in the mirror! Why?

Case 3: The portrait can imagine the role of the Third.

In Figure 2, a charming example is the self-portrait of Rembrandt. Harrison apparently loves this little painting as much as I do. But I do think that he misinterprets the gaze of the young artist. Harrison points out that Rembrandt is not looking at his painting, and he suggests that the artist is looking at an imagined viewer (p.8-10). He provides a detailed view of the painting to prove his point. However, Rembrandt is not looking at the viewer of his painting, his gaze is directed slightly upward, and the imagined viewer would have to stand in a some elevated position more to the right. Actually, his gaze is very similar to the gaze of the Third in the scheme of Luncheon on the Grass, the male sitting next to the female engaging the viewer.

As indicated already in Case 2 about the Second, this is not a sight of himself which Rembrandt could have seen in real life or in a mirror. We have also no reason to assume that he looks at anyone or anything in particular existing unrepresented just outside the picture frame. Rembrandt presents himself as gazing at some idea or “authority”, perhaps inwardly in wonder about his future as an artist.

In the following unique and amazing series of self-portraits Rembrandt demonstrates how he explores his inner potential through a reflection expressed in self-portraits. Thus, the “Big Other” of Manet’s scheme, toward whom the Third is directing the gaze, might turn out to be the most inner self of a genius. Georg Simmel in his analysis of Rembrandt (1916) has described how Rembrandt expresses his genius as a force from within the painting (like an actor expressing subjectively-involved his role on stage), while Velazquez and Manet are examples of artists who express a principle they experience in reality (like an actor presenting objectively-detached his role in a script). Applying the analogy of the theatre, we keep in mind that in painting the activity of the painter combines – like in a puppet theatre – the roles of the author, director, and performing artist. The sociologist and social philosopher Simmel, as I indicated earlier, is a key reference for MyManet.

Case 4: The portrait can express the role of “the Other”.

In this case, the viewer must have reason to believe that the painter has presented himself or herself as seen from an alternative viewpoint. As Lüthy argues, Manet does this by modelling himself in the pose of Velazquez (see Figure 2). In a sense, Velazquez is looking over Manet’s shoulder in the painting “from the back” just like the second woman in Luncheon on the Grass takes the view from backstage. But there is more to it. As I try to show shortly, Manet himself is looking “from the back”.

Here the point is that the painter looking in the mirror (or at a photograph) may take “the role of the other” and try to communicate something about himself or herself, showing not only what one sees, but showing what exists with clues in the painting. Manet consistently avoids “telling stories”, whether about other persons or himself. We expect that “the Other” will appear in his self-portrait only as the formal option of an alternative view, not as some more or less revealing information about his inner mental life.

As suggested above, Manet deliberately shows what he sees, i.e. the mirror image.

Except, the painting right hand holding the brush is not clearly depicted!

This has provoked interpretations by Fried, Wittmann, Lüthy, and others that Manet tries to show “realistically” his fast moving hand making bold brush strokes. He cannot paint it clearly – this “speed-model” holds – because he is moving his hand too fast. Wittmann offers additionally the view – the “close-up model” – that when moving his hand toward the mirror image it comes too close to be focused sharply.

I think both interpretations are not tenable:

The “speed-model” – as I like to call it here – conflicts with the overall impression of the painting.

Manet is clearly striking a pose, probably trying to simulate Velazquez. There is nothing hasty about it, not in his self-portrait and not in the model of Velazquez (see Figure 2). When painting any model, whether somebody else or your mirror image, you want the model to keep the pose, you study the pose, imprint it in your short-term memory, turn your eyes to the painting, and try to make the appropriate marks on the canvas correcting the painted image while doing it. Your head may be turning a bit and perhaps the body, too, but your hand “waits” until you secured an impression and turn to the painting.

A problem arises, when you try – like Manet – painting yourself in the pose of reaching with the brush hand toward the canvas. Still, there is no need to be quick, you just turn and move your hand toward the mirror creating the image of your hand close to the “canvas”. The problem is that in reaching out toward the mirror the mirrored hand also reaches out toward the “back” of the mirror plane and your brush hand will cover up its image! As Manet’s painting shows, you might only see your fingertips, since your eyes are somewhat to the left of the hand.

Figure 3 tries to reproduce the stage of painting and, then, the stage of leaning over to the left to create the mirror image with Manet’s brush hand close to the mirror plane. The mirror image follows his movement, and the hand covers its own image.

As to the “close-up model”, in this movement his mirrored hand never gets closer to his eyes than the mirror. So, we have no basis to assume a blurred perception of the brush hand.

Figure 3: Diagram of Manet painting

and Manet leaning to the left to move his brush hand close to the “canvas”/mirror.

In the movement, Manet has to be careful not to come too close to the mirror with his other hand holding the palette. Apparently, he was not careful enough, since the tips of the three brushes have touched the mirror surface. Being the true realist, he truthfully paints the three little dots – show what one sees!

The three dots, now indicate the mirror surface in the painting – although Manet does not show the mirror explicitly, say, by showing the frame. Manet is playing games with us, again.

Another problem arises with depicting the eyes. Manet is close to his mirror image – remember the three dots – and in this near distance one cannot look at both eyes at the same instant. Manet has to focus either on the left eye (his illuminated right eye) or on the right eye (his left eye in the shadow). Lüthy (2006, p.194) calls the left eye the “active eye” because it actively engages with the viewer, and the other eye the “passive eye” being only looked at by the viewer.

But Manet has again an optical problem. Looking at the active eye, he gets an impression of his gaze to the assumed viewer, but he cannot see his passive eye clearly. Shifting his focus to the passive eye, this eye is not passive anymore but actively looking at him!

In the painting, we now see a little cross-eyed Manet, since being the truthful realist he shows what he sees – just painting first one eye and then the other.

At this point, Manet is clearly leaving a naturalistic realism and accentuates what exists but cannot be seen by him when looking at the viewer with his presented, active eye. The eye in the shadow is somewhat enlarged and the face appears to be a little more frontal. The “other Manet” is looking at him – and at the viewer who shifts the focus to this “other eye”. We are reminded of the too large woman in the back of Luncheon on the Grass or of The Absinthe Drinker representing Manet himself in the background of The Old Musician.

We return to the question why Manet is painting these self-portraits so late in his career.

Most interpretations refer to the increasing health issues which made him reflect more on his mortality, and, in fact, lead to his death only a few years later. I like to propose an interpretation which follows up on the remark by Rubin cited above, namely, that Manet wanted to reassert his version of realism in view of the growing success of impressionism and to return to the “dialogue of gazes” (Rubin) realized eventually in his last masterpiece.

The self-portrait can be understood as an impressionist painting if taken literally – painting your impressions or what you see. But Manet is deliberately showing the mirror image, not – as Fried suggests – because he wanted to show that his quick impressionistic style does not leave the time for reversing the image (1996, p. 397). Manet is playing games with this “realism of visual perception” and demonstrates his own “realism of the body” by showing the inconsistencies arising in the attempt to reduce the world to the visual image.

This emphasis on his self-critical realism against the impressionist explains also, why Manet is referring to Velazquez again after avoiding citations of the Spanish master in the 1870ies.

Manet does not even show the mirror, because it poses no genuine problem for him. For Manet, “there is no mirror to be penetrated” – as Pierre Courthion puts it – “Manet was not a painter of impressions, but of composed instants” (2004, p.33). His art is a “space inhabited by mankind – it is the poetry of space in painting” (p. 35).

I think even his self-portraits testify to the influence of Manet’s compositional scheme. So let us take a closer look at other paintings following Luncheon on the Grass where the influence is more explicit.

See you next week!

Leave a Reply