Charles Baudelaire is said to have influenced Manet to become the painter of modern life.

Modern life is essentially a question of content or what to paint.

How to paint is more a question of form.

Did they agree on what to paint as a realist and how to paint as a realist?

Or even on the meaning of realism?

Clearly, they were close friends and Baudelaire visited Manet almost daily at the time when he created his first masterpieces like Luncheon on the Grass. However, they seem to have great discussions about painting without agreeing on how to do it. Baudelaire reached some prominence as an art critic, but he never valued the work of his friend in a publication.

Although Manet included him in his painting Music in the Tuileries Garden (1862), Baudelaire did not return the favour by declaring him to be The Painter of Modern Life (the title of his famous essay). He chose the popular illustrator Constantin Guys as his example.

Why?

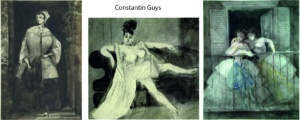

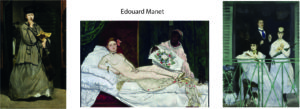

Figure 1: Painting modern life –

three examples from Constantin Guys and Edouard Manet

Manet liked Guys and his illustrations of modern life. As examples of their works in Figure 1 show, Manet might even have taken some of his inspirations from Guys. There is no historical evidence for these cases, but we know that Manet loved to integrate all kinds of material from “high” academic and “low” popular art into his works.

Baudelaire was certainly aware of that. Again, why did he choose Guys and not Manet?

As David Carrier argues, there is no denying that Baudelaire anticipated impressionism as the art of depicting modern life, but did he influence Manet’s art? T.J. Clark in his influential book on Manet “The Painting of Modern Life” (1986) sees a strong bond between the two. Carrier, however, holds that he “does not convincingly link Manet’s painting with Baudelaire’s writing” (1996, p.53).

Carrier cites numerous art historians noting that Baudelaire did not acknowledge the art of Manet. Their explanations vary; however, he finds their explanations unconvincing (p. 50-1).

He goes on to discuss the merits of Baudelaire’s theory of beauty with “the two components of beauty, the absolute beauty of classical art and the relative beauty of fashion, (and) the pleasure we derive from their unity” (p.54).

But he does not pose the somewhat obvious question whether Manet simply had different ideas about painting, and that these ideas were at odds both with Baudelaire and with impressionism.

In the previous Post 10, I tried to show that Manet had an own understanding of realism which deviated from impressionism. Now, we see that his concept is different from Baudelaire’s.

There are agreements, but there are also crucial differences. Unfortunately, Baudelaire wrote extensively on his views, while we have to rely on Manet’s paintings to understand his approach.

Manet certainly agrees with Baudelaire on the political and ethical dimension of realism:

A painter of modern life should show “what exists and what one sees” including the “ugly or evil” (see previous Post). Guys – as the examples demonstrate – is a realist in this sense. Velazquez – Manet’s idol – also painted both beautiful and virtuous and “ugly or evil” people. This is about realism as a content showing modern life.

But Manet does not see himself primarily as a reporter of modern life like Guys, the illustrator.

He also does not aim for a “pictorial poetry of the middle class’s better self”, as Césare Graña somewhat disrespectfully describes the way impressionism showed the life and leisure in modern Paris (2019).

Manet shares with Baudelaire a sincere search for a new approach to painting criticising both the established “idealism” of the academy and of the naturalistic “realism” of Courbet. But he disagrees on the principles of a new realism – on the aesthetic form of realism.

In my view, Manet detects, on the one hand, too much of traditional idealism and romanticism in Baudelaire’s theory of beauty. Manet admires the Old Masters and wants to continue their tradition, but he also is a strong critic of the conventional principles of painting. The question of new principles is not answered by a criticism of established ways, one has to demonstrate a new way, and Courbet’s realism is not the answer for Manet.

On the other hand, looking at the modern ways of expressing a sense of beauty in fashion and popular art, is important to understanding contemporary concepts of beauty. Manet clearly has a love for modern fashion, in his own way of dressing as well as in the dresses of others, especially of women. However, Manet sees a great gap between Baudelaire’s eternal principles of “high” art and contemporary expressions of “low” art in fashion. How can we identify and paint “what exists” in the fleeting impressions of “what we see” in fashion?

This gap is not filled by Baudelaire’s theory: a new consciousness of the beauty in modern life does not, in itself, lead the way to principles of a new modern art.

Manet wants to take a fresh look at the reality presented to him in modern life. And he wants to look as a painter, not as a novelist or poet or composer; his medium are the means of a painter, not language and not the sound of music.

Convinced like Baudelaire that there are more general, enduring elements or structures in aesthetic experience, he wants to concentrate on essential elements and not on fleeting impressions.

And Manet probable was convinced that the concept of beauty carried a strong Romantic bias into Baudelaire’s position which he wanted to avoid. Although, he admired beauty wherever he encountered it as an essential attribute of the person. The beauty may be expressed in the latest fashion including cosmetics, even in costumes on stage, but in an authentic way, not as a mere cosmetic surface. Realism shows beauty as well as the “ugly or evil”.

Among Manet’s principles in the search for a new realism were the realization of simplicity, sincerity, and naiveté.

In view of MyManet, he found a model for the principles and practical performance of painting in the puppet theatre. The focus on essential elements may be visualized by “deconstructing” the Luncheon on the Grass in components like in Figure 2.

Figure 2: “Deconstruction” of Luncheon on the Grass as elements in a puppet theatre

Such structural elements – not necessarily the elements shown in Figure 2 – are his “words” and “sentences” which he aims to organize into a picture. He does not dissolve reality into impressions reflected by a surface but into structural elements “hanging in space” and suggesting bodily and material objects. The objects in the painting are experienced as present, almost touchable. They are organized in pictorial space so as to suggest that they can hide other objects from view, create a sense of space, and imply a wider environment beyond the picture space.

Manet does not want to create an illusion of reality, but a “reasoned image” (see previous Post):

The structural elements and their composition are designed in ways showing reality as a pattern in the painterly medium. The unity of the composition should – in Manet’s view – not be achieved by a “story” explaining what can be seen; the reality of the painting should speak for itself.

These patterns are embedded in the reality around him, but, typically, they cannot immediately be “seen”, grasp and understood without attention and intensive observation. The intensity of Manet’s painting process has been described by many of his models as well as his practice of scraping off the achieved state and starting again in the next session. Manet wanted to capture the essence of his model – if possible in one session presenting a living image rather than a dead copy. This is easily misunderstood as an impressionist attempt to capture the specific moment (like Monet painting the light on haystacks at different times of the day). I think that Manet was trying to discover and present the typical pattern which was showing itself in a specific session clearly – or not. In an attempt to sort out accidental elements he started all over again.

As a consequence, Manet’s models found the session quite demanding and intense, and the focus on underlying, enduring patterns arrested the figures and their activities.

The patterns cannot be “shown” in a painting without experimenting with a guiding scheme and developing corresponding skills and practices. Not surprisingly, Manet preferred working in the studio consulting various sources for his compositions.

This approach toward discovery of underlying patterns by experimenting is not taken by idealism – where patterns are “eternal” and guiding rules – nor by Courbet’s realism – where patterns are observed “in nature” and represented.

Lüthy describes Manet as taking the “position of an impossible Third”: The position of a “realistic formalism”.

He combines reflective imagination with a creative practice which is not “representation” of reality but an experiment. “In this experiment questions of form and content, artificiality and realism merge into one another” (2003, p.116).

The experiment is realized not just in one painting but in a series of pictures and studies with Manet trying to find a satisfactory solution. This is why Lüthy tries to identify structural elements and the variations of their composition over a series of Manet’s paintings.

As reflected in the concept of “reasoned image”, this approach is not entirely new but characterizes the scientific methodology as it developed until the beginning of the 19th century.

Lüthy is aware of the importance of science, however, he tends to refer to scientific insights from physiology and psychology employed by impressionists to express subjective experience of modern life in their art.

Manet is, in a sense, more oriented toward scientific objectivity. In science, subjective experience is questioned as endangering objectivity. If realism claims to represent objective reality, it has to look beyond the immediate impressions to discover the more enduring structures of experience.

In terms of the psychology of painting, Manet is more a cognitive psychologist (like – later – the cognitive Gestalt psychologists), while the impressionists are influenced by the psychology of perception of Gustav Fechner (1801-1887) and Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920).

In philosophical terms, Manet is a practicing phenomenologist – we know virtually nothing about his philosophical inclinations – who tries to discover the inherent structures of experience rather than a positivist who takes sensory evidence as given.

The analogy with science should not be taken too far. Manet clearly sees himself as an artist, not as an applied scientist of any kind or discipline.

But there is another interesting parallel to the situation of science.

The insight into the problematic impact of subjectivity of the scientists themselves produced toward the end of the century the need to control subjective influences by methodology, both on the level of rational discourse and controlled observation.

Manet seems to be aware that his rejection of idealism and naturalism raises the question of how to justify his impossible third position of “realistic formalism” (Lüthy). The impressionist option – wholeheartedly embracing the expression of the individual artist’s subjectivity – was not his ideal. But conformity with established traditions, not only in art, had largely lost its legitimacy in modern society.

One way of justification is the belief that – at least in the long run – art tradition will reveal the value of his art; that is why he all his life sought the recognition of his art by institutions of art – like museums and public exhibitions. However, the acceptance of the “authority” of art traditions had to be critical, which means for Manet that elements of previous art should prove their value in contemporary experimentation.

Another way is the acceptance by a critical art community – by the avant-garde. Therefore, Manet sought the critical discussion of art among artists and valued the view of others.

A third way – as argued in MyManet – is Manet’s “going social” in his painting practice by deliberately implicating the viewer, the model, the “Other” and the “Big Other” in his paintings.

This way, he turned his practice into an “open space” reminding himself of taking a self-critical position and inviting others to participate in the experiment.

The medium achieving this participation for Manet is, especially, the gaze of the persons in his painting, not only the gaze toward the viewer, but also the gaze from the back or outward, creating a social space through painting.

To what extent institutions, avant-garde communities, or participative practices can or should determine what is art – and what not – is a discussion accompanying the development of modern art from the beginning. We will return to that question; here, I only want to point out that experimentation in science and experimentation in art, creative practices and consolidating institutions in both realms have to be distinguished because they are guided by different principles.

The primary environment for Manet’s art was his own studio. Figure 3 tries to show how the studio worked as an open space including art of the past, own paintings, models, anticipated or even present viewers (the girl). In the upper right hand corner, the diagram indicates that Manet may be thinking of elements in his The Old Musician (see Post 7). The lines indicate the communication with the gazes and gestures of figures in the painting and the model.

Figure 3: A diagram of Manet’s studio

This situation for the painting process was difficult or impossible to create and to sustain in “open air” – Manet preferred the studio.

The practice also depended on close contacts with preferred models, interested colleagues, and the experience of modern urban life in the art community. Manet missed his Paris whenever he travelled and returned to create his major works from drawings and sketches.

Institutions, communities, and participative practices are social forms in Manet’s scheme which we will encounter again in the discussion.

The creation of a painting is, for Manet, an experiment that runs over a series of paintings. We have looked at pictures that preceded Luncheon on the Grass. At this point, it seems appropriate to look at some other paintings following this “programmatic” painting to see how Manet is varying his scheme.

See you next week!

Leave a Reply