Sometimes life interferes in significant ways with the plans of human beings – actually, it does that on a quite regular basis.

In my case, the plans for this post were intercepted by the Annual Exhibition of the Järvenpää Art Society of which I am a member.

Aspiring to full membership, I need contributions accepted by the jury.

So, I submitted these three paintings:

Figure 1: My contributions to the Annual Exhibition 2021

“After Matisse”

“A Bar near Folies-Bergère”

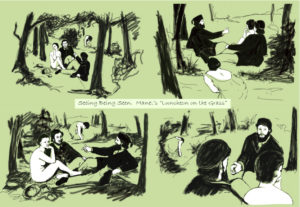

“Seeing Being Seen”

The event clashed with my plans into different ways:

- The preparation of the three paintings submitted took much more time and effort than anticipated. That may be considered a rather usual miscalculation on part of a novice in the “art business”.

But it made it necessary to postpone the publication of my post.

Sorry about that! - The other interference occurred with the planned content of the post and was equally unexpected.

The jury accepted one of my three paintings and excluded two others.

This is also an event to be expected and accepted, but it got me thinking about the reasons why these two were excluded.

These reflections suggested a different theme for the post.

So, I would like to share my reflections on the jury’s decision, because the issue is directly related to MyManet – both paintings present themes on Manet!

The problem may be put in the following way:

Did the jury select a painting and reject two diagrams?

Let me state at the outset that I am not questioning the decision of the jury.

I would like to be – however modestly – proud of having a painting accepted for the Annual Exhibition.

So, to be proud I must assume that the jury was competent making that positive decision!

But then, it makes no sense to question their competence in the other two cases…

Besides and obviously, I have a lot to learn and to experiment on my way to expressing myself in artwork. The experience of preparing my submissions to the event demonstrated that again.

The task of the jury was to evaluate the quality of the paintings and I accept their verdict.

Thus, the quality of the three paintings is not my concern here (but in front of the easel).

My question is more self-critical and, in part, conceptual, and related to MyManet:

Looking at the three paintings, one difference between the selected “After Matisse” and the two “Manets” stands out:

- “After Matisse” (original: Still Life with Oranges 1913) is a still life which does not try “to make a statement” beyond “pure painting”. It just offers an art experience – “art for art’s sake” – as is typical for Henri Matisse. This was also my goal for the free copy. “After Matisse” is not a strict copy, the dimensions are already different – the copy (40×40), the original (94×83). My version tried to catch my impression of the original (as if it would be a still life itself) – and learn something about painting in the process.

- The two “Manets” are not copies, they are “about” Manet and cite elements of his paintings. “A Bar near Folies-Bergère” (acryl, 80×100), obviously, cites Manet’s famous “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère” (1882), but it includes also references to four other bar paintings of Manet (besides a citation of Velazquez).

I will return to my painterly interpretation of Manet in a later post when looking at the original Bar as his last application of – what I call – Manet’s scheme.“Seeing Being Seen. Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass” (digital drawing) presents a sketch inspired by the gazes of the four figures of Manet’s scheme in Luncheon (lower left)

– with the gaze of the First (the nude) looking back at the viewer,

– the gaze of the Second looking towards the other two persons,

– the gaze of the Third to the more distant “authority” beyond the picture space, and

– the view looking “over the shoulder” of the “Other”, the bather in the background.

Thus, the sketch combines the different views which the viewer would have walking around the group and meeting their eyes (or looking over the shoulder).

The participant viewer would experience “seeing being seen”.

Both “Manets” are “about Manet” in the sense that they are conceptually inspired by MyManet. They are not only paintings but illustrating arguments: They support the general thesis that Manet is applying – consciously, or not – a certain scheme.

In case of “Seeing Being Seen”, this is quite obvious; in case of “A Bar near Folies-Bergère”, it is more subtle, since the painting presents an own application of the scheme. However, the accentuation of the perspectives of the main actors by straight lines crossing the painting suggests quite strongly that there is some kind of model or scheme at work.

While the “Matisse” is straight forward a painting, the “Manets” can be seen (also) as diagrams.

The question arises whether or to what extent the jury preferred paintings over diagrams.

Or, since I do not want to discuss the criteria of the jury:

Did I make the mistake that I painted (too much) diagrams rather than paintings?

Clearly, in MyManet the aim is to interpret Manet’s paintings with the support of diagrams.

Did this aim influence my painting of the “Manets” too much?

Another question may be what I learned about MyManet when trying to paint with his scheme or diagram in mind.

This question, I will take up in the following post.

First, let us look at the differences between paintings and diagrams.

The question assumes that there is a substantial difference between paintings and diagrams and that their principles are, to some extent, in conflict with each other.

So, what is the difference between a painting and a diagram?

There is, of course, a wealth of literature on this issue.

And the question very quickly leads into a deep discussion about “what is art – and what not?”.

So, here I like to share only some personal reflections motivated by the three paintings.

We might expect a categorical difference between the two concepts based on semiotics.

Take, for example, the well-known distinction between icon, index, and symbol in the semiotics of Charles S. Peirce. This distinction is derived from his fundamental triadic system, here applied to the level of signs:

– an Icon presents certain qualities which it shares with the objects it presents;

– an index represents a certain relation between qualities or aspects,

often a causal law is depicted;

– a symbol is interpreting qualities and relations in some meaningful context.

Following a triadic scheme, we might distinguish between pictures, diagrams, and text. Then, diagrams and paintings appear, at first sight, as categorially different. However, Peirce saw diagrams foremost as visual schemes distinct from logical relations and symbolic language (another triad in Peirce’s system). Therefore, pictures and diagrams both belong to our visual ways of “world making”

which Peirce, by the way, believed to be quite fundamental to our understanding of the world.

On the level of painting, we would distinguish – following the triadic scheme – between the painterly means (like colour, line, shape, brushwork, etc.), the formal composition or design relating elements, and the narrative (“story”) contextualizing the elements. We would point out that Manet is clearly focusing on painterly means, that he follows in his multi-figure paintings a certain scheme, and that he is decidedly avoiding “telling stories”.

In this view, “After Matisse” is clearly focusing on painterly means, “Seeing Being Seen” is the most diagrammatic work, and “A Bar near the Folies-Bergére” attempts a more interpretative application of the scheme.

However, we would not expect that there is a categorial problem in combining painterly and compositional or formal aspects in a painting.

Let us agree that diagrams and paintings are both visual ways of “world making”, but have different aims:

- Diagrams cast information and relations or patterns into a visual form.

The content of a diagram is usually described in a text, but typically the content displayed in the diagram cannot be adequately and practically formulated in a text. Some information and insights depend on the visual medium. “The Art of the Diagram” (Schmidt-Burkhardt 2019) consists in creating a representation which allows us to grasp essential insights visually, literally seeing the pattern in a flood of data. Modelling and experimenting on the computer has enhanced diagrammatic methods dramatically. We are understanding and “making worlds” with the aid of “beautiful evidence” (Tufte 2006) represented in diagrams.

The “truth” of the diagram resides in the adequate representation of the world including possible, past, or future worlds; it depends on knowledge about the world and adds to it. - Paintings do not necessarily represent anything in the world, although they often do or are perceived as representing something. “Seeing-in” a painting something represented or “seeing-something-as” a work of art is not an act of simply recognizing an object in the painting or a painting as art.

On the one hand, our ways of seeing are culturally developed. When we see faces or horses in the shapes of clouds of a painting (or in nature), this does not mean there are those objects independently of our ways of seeing. Our perception applies culturally learned distinctions and patterns, but we also apply these patterns in an act of creative imagination, it is a way of “world making” changing in history and with societal circumstances (Davies 2009).

On the other hand, in the creation of each painting the artist is not simply applying our culturally developed ways of seeing. Painting is also an act of creative imagination and of “world making” which, in turn, may suggest new ways of seeing. This creativity is limited only by the material restrictions of the production. In the virtual worlds of computers, these limits can be stretched to the limits of our innate visual capacities.

Boundaries for this creativity are not so much in the process of production expanded by ever new technologies and media, but in our culturally mediated ways of perception, our understanding of what is art, and to what extent we want to restrict our concept of painting (e.g. to the application of lines, shapes and colours to a 2-dimensional flat surface rather than including sculptures, installations, performances, holograms, film, photography, etc.).

The “truth” of painting resides in the way it enriches our aesthetic experience of the world and by (eventually) being perceived as belonging to the “world of art”. The cycle of production and reception of ways of seeing involves learning processes and takes time. In the case of Manet, his contemporary audience did not (yet) understand how to align his painterly innovations with established ways of seeing.

The aims of adding to our knowledge and the aim of enriching our aesthetic experience do not necessarily harmonize. Often, we find one aim pursued on the costs of the other. However, as the history of diagrams and paintings demonstrates, diagrams can be very artful without violating the requirements of knowledge, and paintings can incorporate new knowledge about the world without losing their aesthetic quality.

A good example working both ways is the well-known drawing of the proportions of the human body by Leonardo da Vinci (Figure 2) who was an artist and a scientist as well as an engineer.

Figure 2: Leonardo da Vinci (1490) The Vitruvian Man.

The proportions of the human body according to Vitruvius

and four versions generated by the diagram

This diagram is over 500 years old, and it still inspires generating new ideas.

As shown in Figure 3, I have extracted four versions from the original scheme. We can easily imagine that these figures will motivate rather different paintings.

Moreover, the figures suggest quite different socio-psychological states of the person depicted.

We might even associate the four basic emotional and interactional states described in Post 16 with the figures:

- Figure 1 conveys a rather elated and expansive mood reaching beyond the confines of the drawing

- Figure 2 seems rather down to earth established in his own world

- Figure 3 is reminding of the proud and victorious sportsman or warrior

- Figure 4 appears to be rather insecure and vulnerable, perhaps even lying on the ground.

Certainly, these interpretations are not the only ones suggested by the figures, but they demonstrate that diagrams can give rise to a variation of forms and even content (not only) in painting – just like Manet’s scheme, where moving the basic roles of the scheme into different positions of the composition generates different challenges.

Thus, diagrams can be integral and productive structures of paintings, not only on the level of formal composition but also on the level of content.

I have to conclude that the question about the exclusion of my “Manets” has less to do with their diagrammatic content than with the quality of my painterly means. Actually, the decision to submit the “Matisse” was motivated by my anticipation that the focus on painting rather than supporting MyManet with paintings may prove to be the more successful strategy.

Which leaves us with the question, what I learned about Manet’s scheme trying to apply it in my own paintings.

This will be the topic of the following post.

See you in two weeks!

Leave a Reply