Most commentators agree, including the first reactions of critics in the Salon 1869: Breakfast in the Atelier (1968) is perhaps his most enigmatic painting.

It is puzzling to understand what is going on in the scene.

Already the changing titles of the painting in different sources reflect that we cannot even be sure if this scene is before or after a breakfast or rather a luncheon than a breakfast, taking place in a studio or at Manet’s home. We use the title above especially to distinguish it from the Luncheon on the Grass.

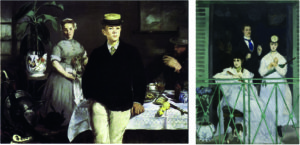

Manet submitted it together with The Balcony which left the visitors equally puzzled.

Figure 1: Breakfast in the Atelier (1968) and The Balcony (1968)

For the contemporary critic Castagnary, both paintings were arrangements “without reason or meaning”; for him, recording the appearances of modern life was not enough.

Manet demonstrated too much “fantasy” and too little “sincerity” and traditional finish (Hanson 1977, p. 30).

Looking at the two paintings next to each other (Figure 1), I find it especially astonishing how different the paintings are in their style and composition although Manet created them in the same year.

Michael Fried (1998) pointed out that the two paintings show a return to the multi-figure paintings after a “Spanish phase” with single-figure paintings following Manet’s travel to Spain.

Here he tried to recover from the harsh criticisms of Luncheon and Olympia by getting new inspirations from his admired Diego Velazquez.

As the art historian James Rubin (2010) suggests, the two paintings document a transition in Manet:

– from Charles Baudelaire to Berthe Morisot;

– from the romantic and naturalistic novelist who died the year before in 1967 to the young impressionist painter whom Manet first met in the summer of 1968.

Both were very close friends but had a very different influence on Manet.

Well, one was an old male friend deserving a memory in the most Baudelairian painting (Rubin), and the other a charming young lady who turned out to be one of the most important members of the impressionist movement.

Quite a transition of friendships!

Since the two paintings were presented in the same Salon exhibition in 1869, they are often compared.

But the first is somehow looking back to paintings in the Spanish and Dutch tradition, the second is moving forward integrating impressionist influences.

So, it is not surprising that The Balcony is getting usually more attention and is seen easier to understand as testifying to Manet’s modernity.

In view of MyManet, this is not doing full justice to either painting, because there is a focus on the differences marked by the transition, while the common aspects are neglected.

Both paintings – as the reactions confirm – are riddled:

– by the interpretation of the gazes and the (lack of) emotions shown by the figures, and

– by the logic of the composition.

In fact, the divergent gazes seem to seriously disrupt or endanger the composition.

In view of MyManet, let us consider both aspects.

In this post, we take a closer look at Breakfast, in the next post at The Balcony.

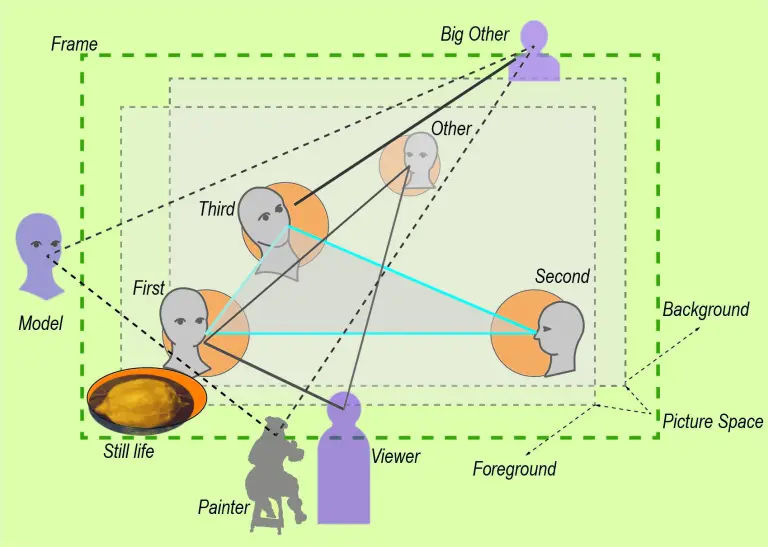

Developing Manet’s scheme in the previous posts, we have seen already how Manet varies the application of the scheme shifting the emphasis between the roles of the figures (First, Second, Third, Other, Big Other) and their position in the picture space (frontstage, middle ground, background, backstage).

In some cases, he might substitute a position by another figure (e.g. the cat for the Third in Olympia).

In some cases, he might omit a position, but implicate it by other means (e.g. omitting the “Other” by closing up the backstage in Olympia).

Additionally, basic emotions are indicated by gestures and postures depending on their relations to each other, to “unrepresented” agents outside the painting, or to the viewer (e.g. the empowered and defiant gaze of Olympia toward the viewer).

Breakfast in the Atelier shows – in this perspective – another variation of Manet’s scheme!

To start, let us look at the dominating figure of the boy (or young man) standing right in front of us (the viewer).

The undetermined age of the fellow gives rise to interpretations that we observe the transitional state of Leon (the model and Manet’s son) between childhood and adulthood.

The gaze of Leon is directed somewhat to the right of the viewer, not looking at the viewer or anything else specifically. He might be contemplating his future as an adult.

Gisela Hopp (1968) suggests that the painting itself shows a kind of dream world, so the boy may be looking at this dream presented to the viewer in the atelier behind him.

Hanson (1973) discusses the painting in her chapter on Manet’s “still lives”, since the boy seems to stand in an arrangement of “still lives”: the weapons in the left forefront, the breakfast on the table (if, indeed, it is a breakfast), and the flower in the left background.

Actually, the figures are also quite “still”: the maid holding the coffee pot, the man peacefully smoking, and the boy holding on to the table without any signs of intention to go anywhere.

The whole painting has a nostalgic or retrospective atmosphere, and as Hanson notes, it invites psychological interpretations: some reference to an underlying or hidden “drama” which the unfocused gazes are “hiding” and all those requisites are “betraying”.

And as Richard Wollheim (1987) has pointed out, this “drama” is not an effect of the portrayal of individual characters. The figures have presence and energy, but no clear personality or motivations to act, whether alone or together (see also Post 2 and his comparison with Edgar Degas).

Still, art historians like Wollheim (and Nancy Locke , among others) have tried to uncover a deeper psychological layer – a personal or family drama – by exploiting, for instance:

– the similarity of the Dutch looking maid with Manet’s Dutch wife Suzanne,

withdrawn in the background,

– the signature “M” on her coffee pot,

– the similarity of the man to the right with Manet himself,

not paying attention to the other figures, and

– the fact that the boy is modelled by their son Leon,

looking out of the painting into his own future.

These interpretations provide interesting contexts, although they do – in my view – not reckon enough with Manet’s inclination to stage an ironic and self-reflexive “theatre”,

and with his sincerity as a painter in designing the scene.

So, I like to pursue another suggestion about the meaning of the gazes in the painting offered by Charles Stuckley (cited in Fried 1998, p.592 in a footnote fn 205).

Stuckley argues that what realist painters like Manet “truthfully reveal are the necessarily artificial underpinnings of the activity of painting per se.” These underpinnings are the reality of the model’s work in the setting of the atelier. Stuckley suggests – in Fried’s words – “that the strangeness of Manet’s Breakfast in the Atelier was the work of Manet’s models, not the painter himself”. And citing Stuckley:

“As if irked by their model’s roles, Manet’s sitters seem to sabotage his efforts at Realism, for they refuse to remove their hats and they leave the table at which the artist had presumably instructed them to remain for as long as it took to complete the picture. Resigned to their lack of cooperation, Manet’s only option was to record people unwilling to hide their genuine impatience with a slow painter.”

(Fried wonders if Stuckley means this humorously, but I think he makes a serious point humorously.)

This imagery of models – coming to the setting of the painting process like to the set of a theatre performance – is also vividly described by Carol Armstrong (1998). In her case the setting is the Luncheon on the Grass, and she also sees Manet purposefully keeping the artificial and theatrical appearance of the scene alive in the painting. The models in her imagery are very cooperative. Nevertheless, their actual behaviour in the setting is reflected in the painting to enhance its Realism – not to “sabotage” it (Stuckley).

Models should – in Manet’s view – act and pose as natural as possible, that is like in everyday life. This is also reported in an often-cited anecdote from Manet’s time of studying in the studio of Thomas Couture. Here Manet is angry with a model striking a classical pose, and he ask him whether he would behave like that when buying his groceries down the street.

I suggest combining this imagery of somewhat detached models with another imagery evoked by the description of performance training in a practical guide for teachers, dancers, and actors.

The authors, Anne Bogart and Tina Landau, describe their method in “The Viewpoints Book” (2005), a method developed in close interaction with postmodern painting and postdramatic theatre in the 1960ies.

Like Manet’s models, a group of dancers or actors enters the stage. Then they are asked to focus their awareness as much as possible on the immediate situation and their position in relation to the other persons on stage.

They are asked not to focus on the others, but rather to keep them in “soft focus”, i.e. in their peripheral vision and in their perceptual and bodily awareness of each other including all the senses.

In this state of “soft focusing” on the “between” of their relations in space and time and embedded in the architectural setting of the stage, they are then instructed to move in different patterns. They are asked to take their impulse to move or to shape their body from the others rather than from their own impulses.

Obviously, it takes training to create in this way coordinated and harmonized group movements on stage.

It is, actually, quite astounding that it works at all! (Visit the examples on Youtube!)

Now imagine Manet’s models taking their places under the guidance of the painter in this spirit.

They got a general introduction into the theme (e.g. scene after a breakfast) but no great “story”. They are assigned their position, but they have to find a posture, gaze, and gesture with which they are comfortable. They know that they have to keep the pose for a while to allow for the painting process.

But as long as their relations are harmonized by their mutual awareness of each other, Manet is not intervening.

This way the models have a certain freedom to “interpret” their gaze, role, and position.

As Struckley correctly observes, this exactly allows for the realism of the scene, and this is what Manet wants to paint!

It is also clear that with a “soft focus” on their relations rather than on their individual mental states and emotions the models will not “strike a pose and keep it” but adjust within a frame of relations with all others.

Their pose will appear somehow “arrested” – if you are looking for “meaningful” activities – but not lifeless!

I think, Stuckley is wrong when seeing “genuine impatience” in their faces and postures, there is something relaxed but intensive about them.

The authors of “Viewpoints” use the metaphor of an act of shooting an arrow with a bow to a target.

The most intensity rests in the moment when the arrow is pulled back, the bow is under pressure, the whole body of the shooter is lining up with the target, but the arrow is not yet released.

The eventual act of releasing and shooting might carry most of the purposeful meaning, but this moment displays the potential energy.

Now looking at Breakfast with this imagery in mind, the three figures show a presence and energy which flows from their awareness of the presence of the others, including the viewer/painter, without directly gazing at them.

This is the reality Manet tries to capture!

To be able to achieve this, Manet is relying on models with whom he has personal and trusting relationships and who engage with his practice – family, friends, or models like Victorine Meurent.

This may also be a reason why Manet preferred multi-figure compositions to portraits, because in this case he himself has to perform in the double role of the “Other” and the painter.

And, obviously, that becomes especially complicated when the person portrayed is an adorable woman like Berthe Morisot…

Certainly, the models cannot just do what they please.

Manet is communicating with them to create the situation he wants – there is a programmatic dimension in the arrangement, and everybody has to take their position and role.

And in each modelling session his vision has to be communicated again, most likely with some changes.

After all, Manet is likely to have scraped off the sketch from the last session – as his models report – and for a reason!

In view of MyManet, an important part of this programmatic dimension is Manet’s scheme.

In Breakfast, Leon has to take the position and role of the Third in the scheme, as I show below.

This implies that his posture cannot be simply “natural”.

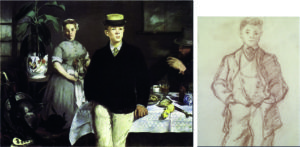

In Figure 2, we confront the painting with a sketch of the boy from the same year in preparation of the painting:

Figure 2: Breakfast in the Atelier and Drawing of Leon (both 1868)

The sketch demonstrates that Manet is perfectly able to make a lively and “naturalistic” drawing of his son.

But in the painting, he is asked to take his hands out of the pockets and to look out of the painting. He also has to lean slightly back to rest on the table connecting with the man behind him resting his elbow on the same table, while the maid is arresting her approaching them.

The energy of dancers with a “soft focus” on their spatial relations to the others permeates the atelier!

This is less than the dynamics of a “good story” or a “family drama” but capturing the reality before Manet’s eyes.

This brings us to the second riddle of Breakfast, the logic of its composition.

Comments on the painting agree that the painting shows an arrangement of somewhat arbitrary figures and other elements in a rather strict composition. The elements seem all related to Manet’s biography and previous paintings, but the logic of their composition appears non-transparent.

Lüthy describes it as “situative incoherence” bound by a “planimetric order” (2003, p.35).

It is as if Manet is taming the diverging forces on the social content level – produced for the viewer by the uncoordinated gazes and the unrelated meanings of the requisites (still lives) – by a compositional order.

This order creates a unity for the viewer on the design level of shapes, colours, and spatial relations. Lüthy sees the logic of the composition in these dynamics of incoherence and order between the elements of the picture and the relationship to the viewer.

In view of MyManet, these dynamics capture an important aspect of the composition. However, there is more structure in the dynamics as the opposition of inner “incoherence” and stabilizing order for the viewer suggests.

Above, I have already argued that the inner “incoherence” might better be understood as “unfocused” unity created by the figures being aware of each other. This compositional unity is supported by the hidden order of Manet’s scheme: the figures have a position and are aware of their roles.

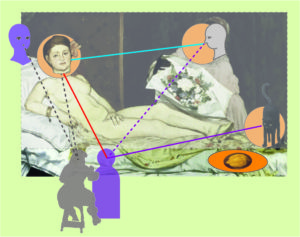

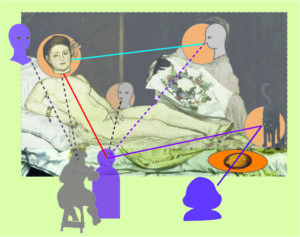

This hidden order becomes apparent when we apply the scheme to the painting as in Figure 3:

Figure 3: Manet’s scheme applied to The Breakfast in the Atelier (1968)

The most striking variation in the scheme is clearly that Leon in the position of the Third is moved onto the frontstage.

This creates a dominant position and role for him. We have indicated already that interpretations see the boy looking “at his future”, his future role in society. In view of the daring position he occupies almost encroaching onto the viewer and breaking the “fourth wall” separating the stage from the audience, we should interpret his role also as challenging painterly traditions of composition.

Comparing the position of the boy as the Third with the positioning of Christ as the Third in Christ Mocked by Soldiers, we see how dramatically the Third is moved against all rules to the front (see Post 14).

Thus, the boy’s gaze is directed at the Big Other in Manet’s scheme.

The maid is taking the position of First engaging the viewer.

However, she is doing that from a position in the background. Nancy Locke (2001, p.130) rightly observes that the triangle of the Luncheon – with the nude (First) in front and the man (Third) behind her – is here reversed.

This position provides some depth to the triad, although the effect is more to push the Third even more to the front, since behind her is only the wall (or painted coulisse) sealing off the back. (In an earlier draft, there was a larger window behind the triad which Manet has painted over hanging a small painting on the dark wall.)

The Second, the man to the right, also shows a striking variation of the scheme.

He is moved far to the right, even cut off by the frame. From this position, he is looking not at the others but straight across the picture space to the left. He is focusing on nothing in particular, may be even lost in his own thoughts.

But he is establishing the middle ground of the painting – occupied by him and the table – as an own layer between the boy in the foreground and the maid in the background.

This distinct distribution of the three figures over three different layers of the painting must have been an essential element in Manet’s experiment with the scheme!

The dominant role of the figure frontstage must have been a compositional challenge which Manet balanced with a prominent still life in the front:

the theatrical arrangement of weapons and, again, the black cat, his signature animal from the Olympia (orange circle). Additionally, he lets the bright yellow lemon almost drop from the table to the right (orange circle).

So, this scene of the “puppet theatre” is clearly talking to the audience from the frontstage.

Finally, the white flowerpot to the left plays an interesting role in the composition.

On the one hand, it is placed somewhat behind the figure of the maid; on the other hand, it is painted surprisingly bright and colourful, even with Japanese motifs. It is pushing forward from the back – and in this feature – the pot is reminding of the second woman in Luncheon on the Grass looking from the back! The pot is also somehow “too large”, not a face but clearly “facing” the scene and the viewer.

Indirectly, it is accentuating the void space between the pot and the weapons supporting the independence of the middle ground across the composition.

Thus, we may see the position and role of the “Other” taken by a flowerpot!

We see an inversion of the scheme from Luncheon on the Grass and, as I would like to show in the next post, the painting The Balcony is displaying yet another variation of the scheme!

See you in two weeks again!

and Venus of Urbino by Titian (1538)

and Venus of Urbino by Titian (1538)