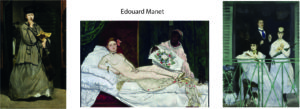

Manet was a republican and not particularly religious. As a realist, he rejected the Romantic, mystic, and religious themes of the past and preferred subjects of contemporary life.

Still, he painted two major works portraying Jesus Christ.

Why?

Art historians are somewhat puzzled by this fact. One usual explanation is that Manet wanted to preserve art traditions, although in a distinctly modern way (Rubin 2010, p.99). Another explanation points out that Manet at this stage was still searching for his own style and theme, and tried all traditions including religious themes

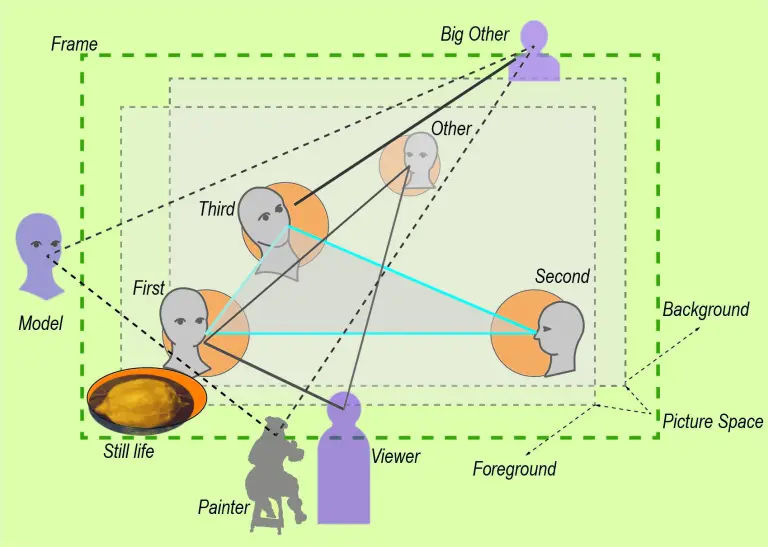

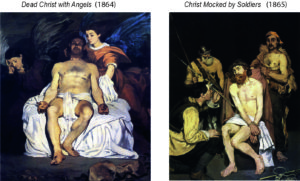

Figure 1: Manet painting Christ

At the time, an influential book by Ernest Renan (La Vie de Jesus 1863) described the life of Christ realistically from a scientific, historian perspective. It is generally assumed that Manet wanted to demonstrate that he could transpose not only the nude (Luncheon on the Grass) but also depictions of Christ into modern times.

Typically, art historians do not like the two paintings of Christ, Dead Christ with Angels (1864) and Christ Mocked by the Soldiers (1865). This holds for critics at the time as well as more recent evaluations.

Some find them horrible (Wollheim), see them as his most eclectic works (Hamilton), and books about Manet usually pay little attention to them – if at all.

Rubin offers an illuminating view on Dead Christ (we return to it later), but, curiously, fails to discuss Christ Mocked although showing the picture.

The paintings are considered “history paintings” (Krell; Hanson), and it is quickly added that Manet painted no more works of that genre afterwards.

The most favourable remarks tend to point out that Manet counterbalanced his more contemporary themes with a religious work to appease the jury of the Salon exhibition. He submitted Incident in the Bull Ring (later cut-up by Manet) with Dead Christ with Angels in 1864 and Olympia with Christ Mocked by the Soldiers in 1865.

The strategy did not work – the critics liked the Christs even less.

I must admit that they escaped my attention, too – until MyManet.

Again, why did Manet paint them, and in the way he did?

Part of the explanation is given by the motivations above.

Hanson (1977) has taken a more favourable view on the two paintings:

“Manet has attempted to make a universal image for all time, any time, all people and all places which has to do with human feelings on a level shared by saints and heroes with most ordinary men (p. 110).”

Especially for Christ Mocked, I see also another motivation, namely, to experiment with his newly developed scheme!

Although, both paintings are not obvious applications of the scheme.

In view of My Manet, they are experiments with the scheme, and Luncheon on the Grass is, in turn, one of its possible variations.

This needs some explanation.

The formal scheme allows not only for adaptations according to the theme at hand.

It can also be used to systematically generate new compositions.

The “Trick” is to change the positions of the main actors on the “stage” and “fill in” the social space created with some suitable scene and corresponding roles.

For instance, each of the three members of the triad could occupy the central position, while the others take up supporting roles. And the variation may include the position and role of “the Other” and “absorbed” figures. Obviously, Manet is not rigidly applying a scheme. But My Manet assumes that the scheme is influencing the way he envisions and composes chosen themes.

Especially intriguing is the option to place the First – looking at the viewer – in the background and moving the Third – looking at the “authority” – to the front.

Other options are available, but when you are set to paint a Christ, what is more convincing than placing Christ (as Third) front and centre turning his gaze up to his Father (the “authority”)?

This happens in Christ Mocked, therefore, we will look at this painting first, although Manet painted Dead Christ with Angels a year earlier.

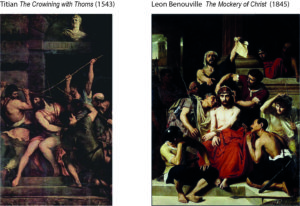

Hanson points out that Christ Mocked has a number of sources, the most often cited is by Titian The Crowning with Thorns (1543) in the Louvre museum. Her discussion prompted me to search myself a little bit, and I found a painting by Léon Benouville The Mockery of Christ (1845). The painting won the Grand Prix d’Rome and is exhibited in the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris. Although I cannot confirm it, it seems that Manet should have known it. The painting won an award and it represents exactly the tradition of the Academy which he opposed.

Figure 2: Two sources of Christ Mocked by Soldiers

Interestingly, the two paintings suggest that Benouville was also inspired by Titian. The figures moving in on Christ from left and right, the elevation of the stairs, and the composition of the background appear to be quite similar. The gaze of Christ, however, varies:

Benouville chooses the gaze at the viewer,

Titian diverts the gaze to the side, and

Manet lets Christ gaze upward and beyond the scene.

We know that Manet liked to “copy” other sources, we saw this practice already in Luncheon on the Grass.

If Manet used these paintings as a reference, then, we also should assume that he deliberately decided to direct the gazes in his version of the scene – as he did in the case of Luncheon. In fact, Manet painted a head of Christ in the same year with the gaze turned down – experimenting with a fourth, “absorbed” option!

Titian shows us a scene which is characterized by the violent dynamics of the crowning with thorns.

The viewer is expected to be moved in empathy with the pain of Christ, but the viewer is not directly engaged.

Therefore, we focus on the comparison of Manet and Benouville.

Figure 3: Application of Manet’s scheme to

Christ Mocked by Soldiers and Benouville The Mockery of Christ

In Figure 3, the two paintings are displayed with some additions:

– For Manet’s version, I have added a diagram with a variation of his scheme.

– For Benouville, I took the liberty to mirror the painting, to shade off some of the soldiers, and to copy Christ’s head from Manet into the painting.

I think the correspondence between the paintings is striking.

Perhaps the most surprising detail is the face of the soldier facing the viewer. It seems that Manet has portrayed the same soldier with the same beard, just in a different mood.

The soldier kneeling before Christ could also be the same person (– at least, they could be visiting the same barbershop).

The third soldier turns his head in the same way toward Christ, only in Manet’s version he borrowed the helmet from the (shaded) soldier sitting on the stairs.

The correspondences with Benouville’s version support the view that Manet is creatively applying the composition of Luncheon on the Grass!

But let us have a closer look at the diagram analysing Manet’s Christ Mocked.

In view of My Manet, Manet has applied his principles to the painting of Benouville (and Titian):

The scene is transposed into the presence – at least, the costumes of the soldiers avoid clear reference to the past and could be selected from any theatre fundus at the time.

Critics have pointed out that the whole setting reminds of a stage rather than a biblical scene of the past.

The number of persons is reduced to the essential figures in the scheme, with the exception of the kneeling soldier to the left.

Manet wanted this additional figure, probably, for the same reason as Benouville, namely, to lead the viewer’s gaze to the face of Christ. Since Benouville’s Christ is staring out toward the viewer, one may question the need for this onlooking figure in his case.

In Manet’s version, we are reminded of the onlooking figure in Velazquez’ The Drinkers (Post 4) – and Manet can always be expected to make some reference to the Master.

The triad – First, Second, and Third – is placed in a very narrow or “flat” pictorial space, as in Luncheon on the Grass. The engaging First is now positioned to the back, as is the Second looking from the left.

The interaction is, again, somehow arrested emphasizing the structure of the relations and leaving the question open how the interaction will resume.

The effect is that the viewers attention is drawn to the vulnerability of Christ, and not to the ongoing aggression and mockery by the soldiers.

A variation of the scheme is apparent in the position and role of the “Other”.

It is interesting that Benouville does, in fact, include onlookers from the back (green ellipse). Even in Titian we might see this role taken by the sculptured head in the background.

Manet, apparently, decided that shutting off the background with a black “coulisse” will add more to the expression of vulnerability, placing Christ in the spotlight on a dark stage, as it were.

We may also assume that the dominance of the unrepresented “Big Other”, God Father, induced Manet to leave out the “Other” and have the black screen suggest the “Other” behind the scene.

Additionally, the First looking from the back would compete with the “Other”. So, Manet rather chose to accentuate the gaze of the First by creating a diagonal toward him. The gaze of the kneeling soldier is directed to Christ but also beyond to the First. The kneeling soldier doubles, in a way, as onlooker and the “Other” looking from a different perspective on the scene.

Remarkable is, moreover, the foreground.

Typically, Manet inserts a little “still life” (indicated in the diagram by our lemon icon). The rope and the arrow on the right side are balancing the foot of the kneeling soldier, both reaching out into the viewer’s space.

In the middle, we are confronted with those over sized feet which create the impression of a close-up attracting and repelling the viewer at the same time, shortening the distance to this vulnerable body.

I wonder if Manet is having some insider fun with these feet. Titian shows Christ with powerful legs fighting the crowning, while Benouville has Christ’s feet feebly peeking out underneath the robe – and then adds the soldier’s feet occupying the immediate foreground (Figure 3).

It must have been tempting to make a caricature of those extremities.

Seeing Christ Mocked by the Soldiers in the perspective of MyManet demonstrates that Manet is developing his formal scheme further. This is the multi-figure painting following Luncheon on the Grass only a year or two later.

It is the last time that Manet choses a religious theme, and it is also ending the early period strongly under the influence of the Old Masters.

But it is not the last painting experimenting with the scheme.

The next multi-figure painting, again experimenting with the scheme, will follow three years later with The Breakfast in the Atelier (1868) (often titled The Luncheon, but I want to avoid confusions with Luncheon on the Grass).

Now the painting will be unequivocally a transcription of modern life, although Hamilton still has the “curious feeling of figures arbitrarily arranged in modern settings rather than seen suddenly and as suddenly set down on the canvas“ (1969, p.130). This stage, he sees already accomplished by Claude Monet and Pierre-August Renoir.

But Manet has his own agenda, not totally compatible with impressionism.

However,

before we follow Manet to his next experiment, I would like to discuss the other painting of Christ – Dead Christ with Angels. In this case, we will discover the influence of the scheme but not a straightforward application.

And, Yes, I still owe you a post on Olympia (1965), the other great scandal of Manet’s breakthrough.

But a step at a time, first the Dead Christ and then the living prostitute Olympia.

See You next week!